Location, location, location. It’s the familiar mantra of the property industry, but does it also apply to the fluid, global world of art and antiques, even in our 21st-century, always-on world?

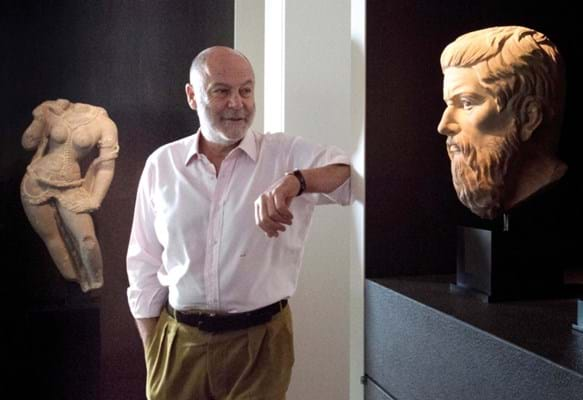

When it comes to London, John Eskenazi, the renowned dealer in Asian sculpture, thinks so. It is the reason he set up Asian Art in London in 1998, and why he believes the event, which celebrates its 20th anniversary this November, stands out from its rivals in New York and Hong Kong.

Eskenazi, who moved to London from Italy in 1994, remembers being enthralled by a city that “seemed like the great bazaar of the world”. But after a few years, he noticed that the auctions were moving to New York and were starting to shift to Hong Kong.

A report in The New York Times in 1997, which described “the eclipse of London” by New York as a leading centre for Asian art and antiques, partly because of the launch of a specialist art fair there, confirmed the trade’s concerns. Jacqueline Simcox, the Asian textiles specialist, remembers reading it with some indignation, given that London had a “vast number of dealers in Asian art compared with New York”.

Eskenazi decided to act. Wisely, rather than set up a rival fair, he and a group of like-minded dealers (Roger Keverne, current chairman of AAL, was a key supporter) insisted their new event must draw attention to London’s unrivalled strengths: scholarship and expertise.

“I felt that what made London special was the quality of its dealers – not only the great auction houses – plus the scholars, the shippers, the photographers, the restorers,” says Eskenazi. “These people are the backbone of the art trade. So I thought, rather than have a fair, we should encourage collectors to see dealers in their galleries and shops – to see them in the workplace to understand their knowledge, their taste and their personality.”

The event was an instant success. “People liked the formula,” recalls Eskenazi, “moving from one gallery to another, and the cocktail parties. It was a very lively scene.”

Firm Fixture

Fast forward 20 years and AAL, which takes place over 10 days in early November, is a firm fixture in the diaries of international dealers, collectors, academics and museums. From the start, it has hosted around 50 exhibitors, including auction houses. Today, it attracts around 10,000 visitors, according to Virginia Sykes-Wright, director of AAL.

The yearly calendar features not only dealers’ exhibitions – sometimes on meticulously researched esoteric subjects – but also auctions, debates, courses, museum events, seminars and lectures by leading academics.

It is, Sykes-Wright says, “a place to look and learn, and look and buy”. Its popularity has, as Eskenazi hoped, ensured that London has remained on the map, and the template has been eagerly copied by New York and Hong Kong. And while the mega bucks, in terms of auction sales, belong to those two cities today, AAL remains relevant largely as a centre of learning “and because it is easy to trade here”, says Sykes-Wright.

Transparency is another bonus. London’s expertise, combined with its business and legal trustworthiness, and lack of red tape, is an asset for collectors with serious amounts of money to spend. AAL has reaped the rewards of the boom in Chinese antiques over the past 20 years and has helped generate some spectacular November sales.

“Asian Art in London is a place to look and learn and to look and buy”

Virginia Sykes-Wright, director of AAL

Runjeet Singh, dealer in Asian arms and armour, and board director of AAL, rejects the idea that the event has become too China-centric. “Middle Eastern, Islamic and Indian [art] is represented very strongly, as is Japanese. Himalayan, Korean, and south-east Asian also has several specialists. It is one of my goals as a new director to try and correct this belief and encourage the focus to be shared equally among the Asian cultures.”

Indeed, AAL claims its academic credentials are the way it can open collectors’ eyes to subjects that are still affordable. Singh says: “If you deal in a niche Asian field, then this event can provide a platform to be recognised internationally. Since I have joined, I have sold to collectors who have never bought, or even considered, arms and armour.”

Even the rapacious growth of online trading – a seismic change since 1998 – doesn’t threaten the existence of AAL, but reinforces its entire raison d’être, Singh argues.

“It is my goal to ensure AAL’s focus is shared among Asian cultures”

Runjeet Singh, Dealer in Asian arms and armour

See, Touch, Handle

“Many serious buyers want to touch, see and handle pieces in person,” he says. “Works of art cannot be fully appreciated from a screen. In addition, collectors want to meet the dealers behind these online empires. A dealer’s credibility and knowledge is a hugely important aspect to a collector when considering a purchase, and this can be demonstrated at an event like AAL.”

The internet may even be a barrier to learning, Sykes-Wright argues. She has noticed the emergence of “young collectors under the age of 35” who have little experience of appreciating and analysing works of art ‘in the flesh’. This has prompted AAL this year to introduce ‘handling sessions’, where an expert will sit down with someone and allow them to touch, hold and experience an item, while explaining its creation and artistic significance. “It’s like a private tutorial,” says Sykes-Wright, “and is a way of helping the next generation gain the experience that people like me took for granted when I started out.”

Contemporary Vibe

Eskenazi believes there are fewer young antique collectors now “because today most younger people like contemporary art”. That change in taste is reflected in AAL and there are indicators that it is likely to grow. Last year, Gregg Baker Asian Art, in Kensington Church Street, held its first-ever contemporary exhibition, a selection of work by the post-war artist Suda Kokuta. It achieved sales of 90%, with prices ranging from £5000-70,000.

This year AAL has partnered with the Chelsea Design Centre for the first time, where visitors can view the work of Art in China and Kamal Bakhshi. Even a limited-edition print celebrating AAL’s birthday has been commissioned from Gonkar Gyatso, the Tibet-born contemporary artist.

This presence of contemporary art at AAL – unthinkable back in 1998 – partly reflects a supply problem, some participants say. You can, as one wryly remarked, “always make another one”. Eskenazi admits that some dealers “don’t like it”, but is not worried about it damaging the brand of AAL, which is so reliant on a sense of history, pedigree and connoisseurship. “It’s not great art, most of the time,” he says. “It’s mostly just merchandise. But it works. It creates a planetary community of collectors and museums, so why not?”

“We wanted to encourage collectors to see dealers in their galleries and shops”

John Eskenazi, Dealer in Asian sculpture

Museum Tie-up

Why not indeed? Part of AAL’s appeal compared with New York’s Asian Art Week event, observers note, has always been its inclusiveness, its love of the interesting, as opposed to the merely expensive. This allows visitors to move cheerfully from a tiny gallery focusing on a decidedly quirky subject, such as tantric sculpture, to the dazzling environs of one of London’s great collections, such as the British Museum or the V&A.

AAL partners with such institutions to promote concurrent exhibitions and talks, and to host a gala party. This year’s will take place in the British Museum’s reopened Joseph E Hotung Gallery.

Even The New York Times has had to eat humble pie, admitting, not long after AAL’s launch, that “New York doesn’t create the kind of hoopla that London does for its [event] in November”.

No doubt there’s plenty more hoopla to come. Eskenazi is confident about the future for AAL: “It’s a formula that has worked very well for the past 20 years, and there is no reason it can’t work for another 20.”

Written by Kate Quill