He collects contemporary British silver including beakers, cutlery, water jugs, bowls and vases.

Hamme offered nine pieces from his collection at south London auction house Roseberys on July 4 but only two sold. Wild Bowl (2008) by Malcolm Appleby achieved £10,000 against an estimate of £10,000-15,000; the dish Storm (2015) by Appleby and Jane Short sold for a hammer price of £3000, against an estimate of £3000-4000.

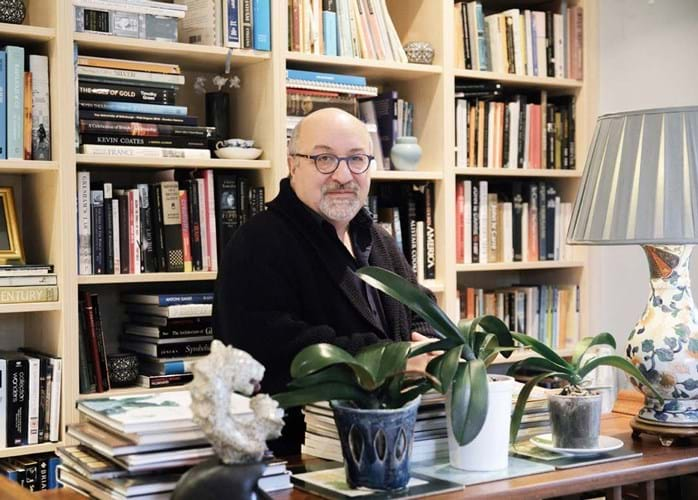

ATG: How did you get the collecting bug?

Gordon Hamme: My wife and I often went to Goldsmiths’ Fair to see our customers. We were based in Hatton Garden and we supplied silver, gold and platinum components, tools and machinery to the jewellery and silversmithing trade so we wanted to see what they were making.

We would often go to workshops and craft fairs, of which Goldsmiths’ Fair is the premier fair, and we would see pieces that we liked and occasionally buy.

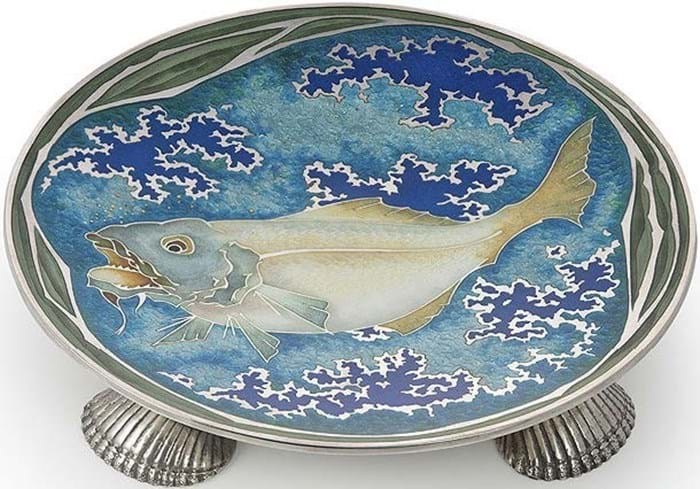

Stormy by Malcolm Appleby and Jane Short, 2015, Sterling silver and enamel dish overlaid with gold leaf, 4½ x 5½ x 1½in (11 x 14.5 x 4cm), sold for £3000 at Roseberys on July 4.

What drew you to contemporary British silver?

I knew nothing of antique silver, and contemporary silversmiths were our customers. We talked to them about what they were doing and started to understand, and it was of interest to us.

Beyond the aesthetic aspect of silversmithing is the skills. I was a jeweller in the early days and I found the skills aspect of it tremendously difficult, and looking at what these people were achieving with metal I recognised the depths of the skills they had to make a piece. Somebody like Wally Gilbert did his initial 10 years of becoming competent and then spent the rest of his life as an autodidact becoming superb.

On top of that, they’re artists. It’s really unrecognised quite how good these people are. You can become a competent, good jeweller I would say in five years; it takes at least 10 years to become a good silversmith.

Dish by an enameller called Phil Barnes, bought by Gordon Hamme in 1988.

Can you remember the first piece you bought?

It was a beautiful dish by an enameller called Phil Barnes. I took a shine to it and bought it in 1988. The first part of the appeal of the piece is its technical prowess. He used a technique which is a gradation of enamelling that had rarely been done before. He perfected this skill of fading the enamel in and out of different colours.

Secondly, I love the subject matter. It’s a big fish in the sea, and it struck me that this fish had a real attitude. If you imagined it as a person, it would be: ‘I’m the biggest fish in the pond here, kindly move out of the way.’ Then the fish is actually blowing gold bubbles. It’s got real personality.

What elements do you look for when considering a purchase?

Normally it’s the quality of craftsmanship and originality. It tends to be when we commission a piece that we want something that’s original and that’s well designed and, occasionally, is pertinent to us. It might be an anniversary or a birthday or an occasion, and so often we do plan ahead.

Would you classify your habit as buying the best there is, or are you driven by the thrill of having something that somebody else has missed?

There’s so much stuff available so if you miss one thing, then you can either commission it again or you can buy something else, so that’s not part of our system of deciding what to purchase. It is a bit of a thrill to commission a piece, especially if you’ve had a certain amount of design input.

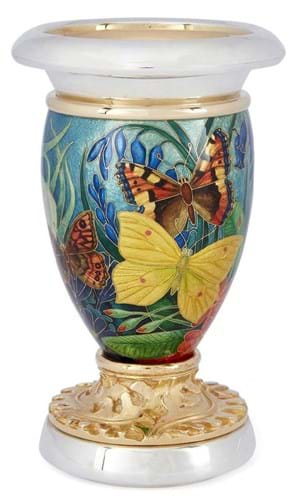

With the Fred Rich piece that was up for sale [Meadow Vase], we did specify that it should be inspired by our garden, which has butterflies and a snake’s head fritillary. Once you’ve done that, then you tend to leave the artist craftsperson alone, because you want to bring out the best in them rather than impose your own ideas. You’ve employed them for their skills and creativity.

The Meadow Vase by Fred Rich, 1997, 6½in high x 4in diameter (17 x 10.5cm). Winner of the Goldsmiths’ Craft and Design Council Goldsmiths’ Award, 1997. It was estimated at £30,000- 40,000 at Roseberys, but unsold.

When commissioning pieces do you see yourself in the grand tradition of patrons through the ages?

No. We don’t see ourselves as grand patrons. Grand patrons would take a maker under their wing and encourage them to do different things. We’re not in that category. We buy a few pieces every year, we’re not significant collectors.

We’re patrons of silversmithing in different ways. I partnered with a silversmith called Brett Payne and he and I did 95 exhibitions over a 10-year period to promote British silversmithing. It was called British Silver Week.

Do you think of your commissioned pieces is antiques of the future?

I actually do. I think several of the pieces are the museum pieces of the future. They demonstrate skill, they demonstrate design and they demonstrate the ideas of that moment.

There’s a piece by Jane Short and Martin Baker [Tricorn Dragons Bowl], which is three dragons chasing each other around the base of a bowl: a Welsh Dragon, an English dragon and a Chinese dragon.

Martin was the carver of the dragons and also did the silversmithing, Jane is a phenomenal enameller, and I thought I challenged them to make a difficult piece.

Tricorn Dragons Bowl by Martin Baker and Jane Short, 1993, Sterling silver and enamel, three hand-carved silver dragons supporting a triangular dish enamelled with vividly coloured flames, 8½in (21.5cm) diameter.

What is the most you have ever spent on an item for your collection?

We often have spent in excess of £10,000 on a piece, which in collecting terms is not a fortune but for us it’s quite a lot of money.

How large is your collection?

I’d say it’s in excess of 100 pieces. Brett is a good friend, we’ve got a fair amount of his stuff. I’ve got four or five pieces by Malcolm Appleby. I’ve got four of Clive Burr’s clocks, which is significant; they’re a combination of silver, crystal and enamelling.

Wild Bowl by Malcolm Appleby, 2008, Sterling silver, hand-engraved bowl, 17 x 18 x 3½in (43 x 45.5 x 9.5cm), sold for £10,000 at Roseberys.

Why did you decide to offer nine pieces from your collection?

We were testing the market. We’re moving house so we’re downsizing and we haven’t got space for keeping everything. We tend to store a lot of it so it’s sitting in storage or not on display, and you think, well, let somebody else enjoy it.

Is there a piece you’re still looking for?

No. I would say we’ve gone beyond that stage in our lives. We were commissioning for good reasons – we were helping our own customers/ friends – and those reasons have stopped now. We’ve got all these wonderful pieces that we do rotate from storage into display in our house, and that’s enough. I think we will rarely commission pieces.

How has the market changed during your time collecting?

It’s changed fundamentally from the point of view that the really mega collectors are collecting less. These are people in the Middle East and Far East.

When I first came into the trade in the 70s and 80s, there was a huge silversmithing industry that nobody knew about and they were supplying the Middle East and Far East with extraordinary pieces. It gave a skills base, especially to south-east England, which has never really been matched.

There were hundreds of people who had amazing skills, that’s much reduced. So the industry itself is much smaller and the volume of pieces which are being commissioned is less.

What advice would you give a young collector?

Spend what you can afford and buy fewer pieces but better pieces, the best quality that you can find. Talk to the silversmiths, find out what they’re doing and see what they’re enthusiastic about, and that’s going to be the best pieces.

I would start with beakers. You can find beakers at the moment that are 20-30 years old at the dealers, so they’re relatively recent, and they’re not expensive at all – a couple of hundred pounds.

Something that probably cost someone £500 is now £200 or £300. I think that’s tragic. Thirty years later, the piece has halved in price.