After a career in market research he opened the Museum of Advertising and Packaging in Gloucester which moved to London in 2002 and became a charity: it is now Museum of Brands in Notting Hill.

He has also curated exhibitions at other museums including the V&A. He has produced many books as well as a documentary on ‘throwaway history’. Here Opie tells ATG about his passion.

ATG: How and when did you get the collecting bug?

Robert Opie: For many the collecting bug begins in childhood. It did for me – stamps, coins, stones and Lesney Matchbox diecast vehicles. The difference was that the family home I grew up in was a bit like a museum, the rooms were lined with books and old toys were displayed in cabinets. My parents were the folklorists Iona and Peter Opie. My apprenticeship in collecting had a guiding hand. For example, my father suggested that the boxes the Lesney models came in should each be dated and priced.

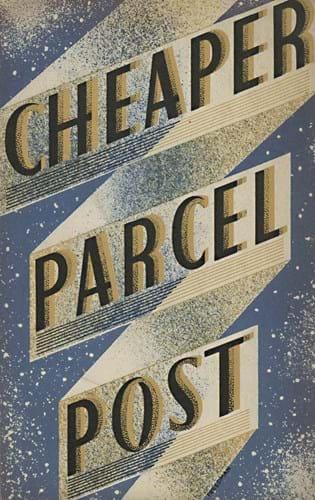

It was all fun. However, I felt that there should be a point and a purpose to what I was saving. I was never going to have a better stamp collection than thousands of other enthusiasts. So I moved my interest in philately to postal stationery and joined the Royal Philatelic Society. (Later, I gave them a talk called A Load of Rubbish, which compared postage stamps to the many varieties of Heinz baked bean can labels.) Even so, this didn’t cure my desire to find a subject where I could be a pioneer.

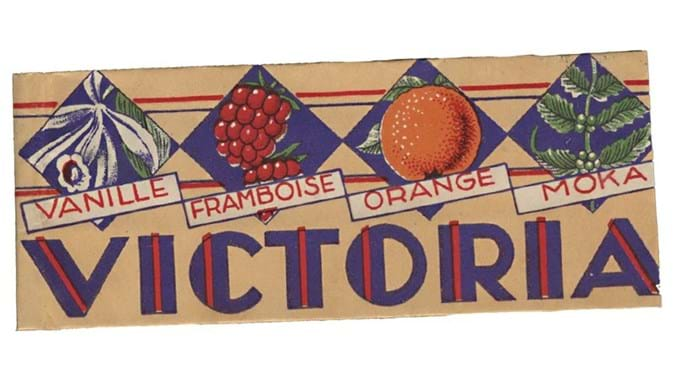

Suddenly it came to me that the answer was all around me. Packaging! Nobody seemed that interested in keeping a record of it. Yet it was transforming the way we lived, and the evidence was being literally thrown away. Just like stamps, there were new products coming out all the time.

That realisation came to me when I was 16 years old. I was hooked. I was now saving history – cereal boxes and yogurt containers, biscuit wrappers and tea packets, squash bottles and soap powder cartons. Trips to the local newsagent meant asking the shopkeeper to save me the confectionery display material from the window.

How did this develop?

It was a few years later that I realised it should be possible to find earlier examples. In 1969 I had heard that the Round Pond in Kensington Gardens was being drained for the first time since the 1930s. I went to have a look. To my astonishment there were some old milk bottles in the mud flats.

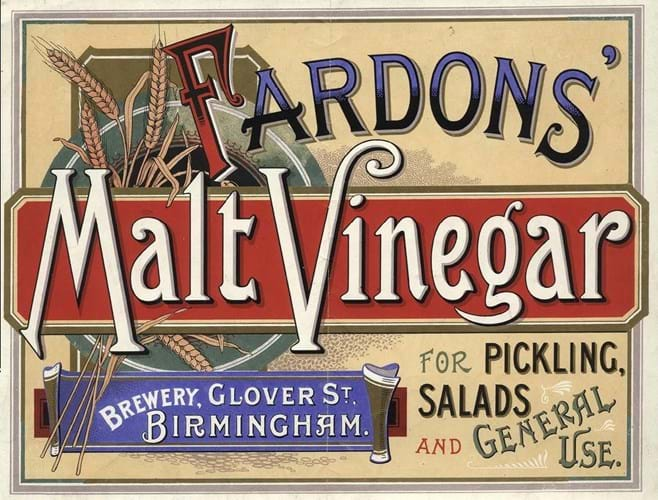

I gathered together six examples. Now the search was on to see where else I could find our throwaway history – places like Portobello Road market and general antiques shops perhaps – and there it was, potted meat paste jars, tobacco tins and boxes of starch powder with early brands like Ovaltine, Quaker Oats and Fry’s chocolate, Rowntree’s cocoa, Hudson’s soap and Oxydol.

How did you develop the collection

I was now going to attempt to fit the pieces together like some giant jigsaw puzzle. Some items had survived because they could be dug up, and others (such as tins) because they made useful containers. However, paper labels and cardboard wrappers were less abundant... but surely, I thought, some of the millions produced must have survived. Fortunately for me, there appeared to be enough material to create an interesting display.

How did your exhibition at the V&A come about?

I approached the museum. They could see its potential and let me design and curate an exhibition. I had two years to plan it. Called The Pack Age, a hundred years of wrapping it up, nearly 3000 items were carefully fitted into one gallery, opening at the end of 1975 for seven weeks. At 28, I was the youngest person to hold their own exhibition at the V&A.

I felt that it was going to be a success; it just turned out far better than I was expecting. I was given a tiny office and a telephone to drum up publicity.

I phoned Noel Edmonds who I knew from my marketing/PR days, and he gave me a couple of plugs on his morning radio show. It all helped. The Times covered it three times. Keith Waterhouse writing in the Daily Mirror exclaimed: “For me, it was like standing on the three-legged stool and peering into the pantry cupboard of my childhood home in the Thirties.” The exhibition was a turning point. It proved to me that there was an appetite for this type of nostalgia.

Some 80,000 visitors found themselves talking to strangers, inspired by the sight of a Woodbine cigarette pack or a Lyons individual fruit pie carton, and friends discovered treasured memories when seeing a bar of Fry’s 5 Centre chocolate. It’s amazing how just a packet of Spangles can ignite a thousand memories. Even the V&A’s attendants were animated.

What happened next?

The next step in my journey was to open the Museum of Advertising and Packaging which happened in 1984 in Gloucester. By now I had given up my 16-year career in market research. Thankfully it was still possible to gain media attention, and over the years I have contributed to 300 television programmes and appeared in seven colour supplement features.

The next thing I wanted to tackle was writing a book or two. My first was Rule Britannia – Trading on the British Image published in 1985.

More were to follow, and then the beginning of a series of 10 scrapbooks covering the Victorian era and then each decade through to the 1970s. Over a thousand images were contained in every book.

How has your collection expanded?

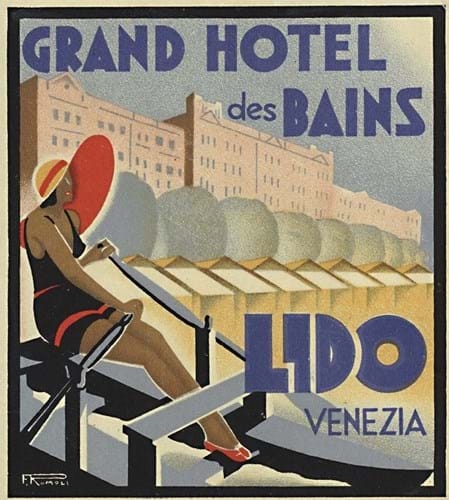

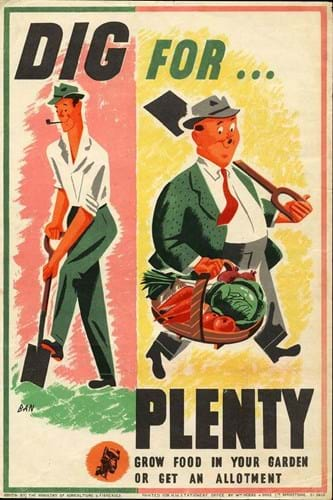

My collection was now extending into most aspects of the consumer revolution – entertainment, travel, leisure, sport, fashion, technology, music sheets, postcards, photographs, royal events, magazines, comics, toys and games, and all manner of advertisements. The scope was endless.

The jigsaw puzzle was now beginning to take shape, and it was possible to see Britain’s remarkable evolution over the past 300 years.

How many items are now in your collection?

I may have 500,000 items, but I wouldn’t recommend anyone to study such a wide subject. The answer is to focus on something that has a point and that you can be enthusiastic about.

How do you describe your collecting habit?

Some may think I have an obsession. No, I’m passionate.

How have you continued to spread the word about your collection?

I created a two-hour documentary DVD In Search of Our Throwaway History with 3500 items.

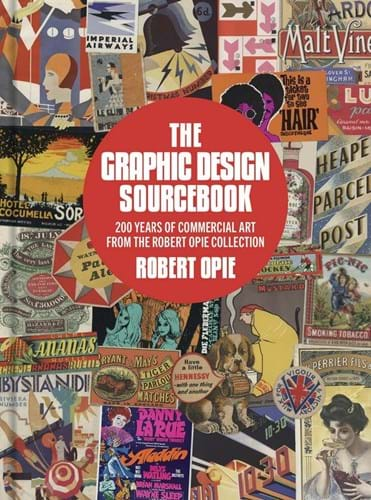

In my latest book The Graphic Design Sourcebook, the emphasis is on 200 years of everyday commercial art. Here are images that should inspire designers, and like me, stimulate the love for illustrated art. Among the 2000 images in this book, you will find things that I picked out of the litter bins of Britain in the 1960s.

Appearing on TV has helped me to spread the word that understanding the consumer revolution is important. After all, we are all still living in it. Perhaps the highlight came in 1989 when I showed the queen around a 1910s grocer’s shop which I had set up as part of the centenary for the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food.

Are you still collecting?

Today, I continue to save contemporary examples of branded products. Many will have made changes to their designs, others will be new varieties, such as Bisto’s pigs in blankets flavour, Walker’s Christmas pudding flavour crisps, or McVitie’s Jaffaween cake bars for Halloween.

Little wonder that I spend so much time in supermarkets.

But having just found a limited edition can of Fanta strawberry and cheesecake flavour, I’m wondering whether it’s time for me to give up collecting. Answers on a postcard please.