Since then she has overseen a major project to make the collection of 130 historic maps accessible to all with the creation of the interactive site Oculi Mundi. Launched last month it features works by Albrecht Dürer, Francesco Berlinghieri and Batista Agnese, and many others.

ATG: How did the collection start?

Helen Sunderland-Cohen: The Sunderland Collection is named for its founder and my father, Neil Sunderland. He has been fascinated by maps since he was a boy. One of his fondest childhood memories is of a map that his uncle owned of Lancashire, including the village where they lived.

He’s always been potty about travelling. Even though he studied engineering, he spent time during university doing an anthropological expedition in Ethiopia, for example. He also adores Treasure Island and Lord of the Rings, so I suppose one of those would have been his first map. He started collecting in earnest over 50 years ago, really as a personal passion, rather than with a mind to building a collection.

When did you get involved?

It’s happened increasingly over the past eight years. I read history and east Asian studies and have always had maps around, and when I moved to London a few years ago, I took over management of the collection.

What is the focus of the collection?

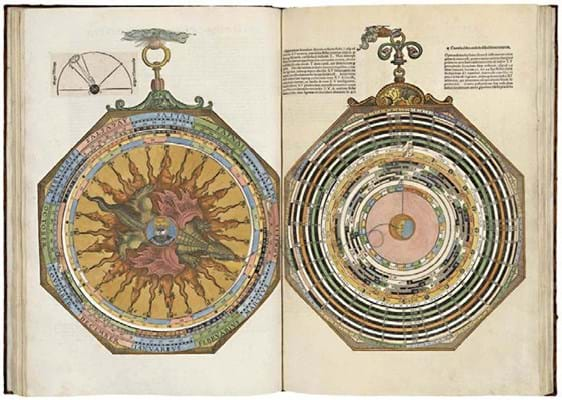

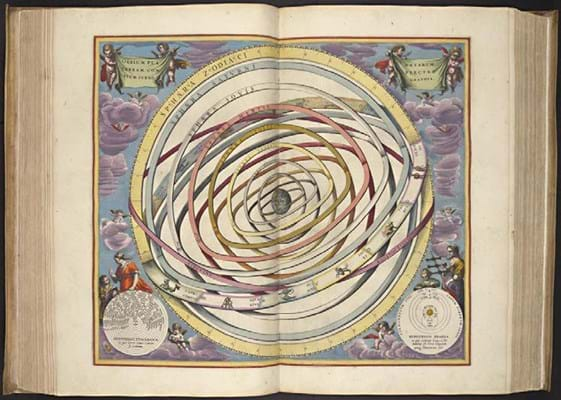

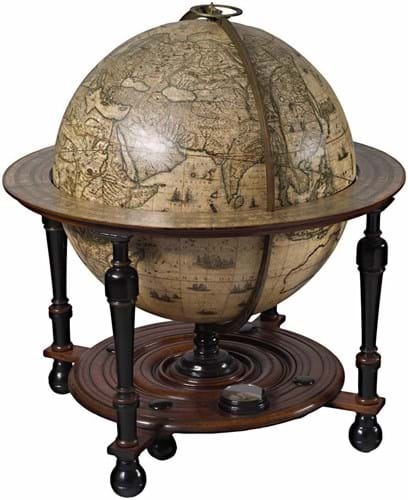

It comprises world maps, celestial maps, atlases, books of knowledge, and globes. It evolved organically around several core themes, such as exploration and discovery, the evolution of human knowledge, the transmission of knowledge among cultures, and the development and artistry of mapmaking. We collect from as early as we can until around 1700. We are primarily a European collection but to the extent that it is possible and appropriate to do so, we collect material from around the world in order to have a more comprehensive overview of thought systems and cultures.

How do you display the collection?

Most of the maps are framed and in company offices in Switzerland. However, the atlases and books are in fine art storage after being digitised. This is through our online platform Oculi Mundi, which we have launched to display the works in a meaningful, beautiful way. Many of these items were digitised at the British Library; for the individual maps in Switzerland and some other items, we used freelance imagery specialists.

Why share the collection like this?

Collecting is such a personal thing, but often, even if people want to share it they don’t have the time or the wherewithal. We made a conscious decision that it would be wasteful to have the maps sit in a cupboard. There is so much in a single atlas, let along the various entry points that different maps represent. We wanted to put it out there even if it just gives someone a smile or gets kids excited about these objects.

Tell us a bit more about Oculi Mundi

The name translates to ‘the eyes of the world’ in reference to how many ways there are to look at maps and atlases, and at what they express.

We wanted to do something new and exciting – to provide an environment where people can enjoy the maps and feel as enthusiastic and joyful about them as we do. The site contains super high-resolution images of all of the pieces in our collection, including the maps and plates inside our atlases and books. Visitors will be able to zoom in to see minute details.

It is positioned as an environment for browsing and enjoying, as well as for research with detailed catalogue information.

We have tried to provide useful context - by making it possible to view the items to scale, and offering a list of biographies and a glossary. Accessibility is at the heart of everything we are doing to activate The Sunderland Collection. For this reason, Oculi Mundi is designed to run smoothly at different Internet bandwidths, and on all kinds of devices. It also has physical accessibility preferences built in, like the ability to toggle colours.

What was the first thing you bought?

It is hard to remember that far back! One of the earliest was a first edition of the famous world map by Abraham Ortelius, dating back to about 1570.

However, it had been coloured much later and so we replaced it with a rare Spanish edition of the second plate (1588) and added a third plate (c.1628), both of which are in original hand colour.

Where do you usually buy?

Directly from dealers, or from other collectors – we rarely buy at auction. We work very closely with a couple of excellent map and rare book specialists in London. The Map House in particular has been advising us for more than 30 years. We occasionally buy at fairs – most recently I’ve been to Frieze Masters and the Firsts, London’s Rare Book Fair, which was a real treat. We’ve also been to TEFAF.

What do you look for when buying?

Each purchase goes through about two or three people on our team before being finalised. We always buy what we think are really excellent examples. If the map or atlas is coloured, then it must be contemporary, original colouring. Sometimes it’s a specific state or edition rather than the oldest one. An earlier edition of an atlas might not have all the maps you want, for example, so it’s always getting a bit of a balance or a process.

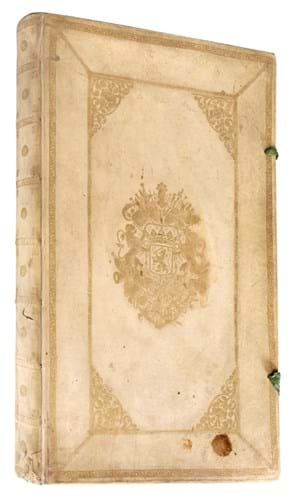

The Pieter Goos sea atlas (1675) that we acquired earlier this year is a good example of our approach. It is a beautifully engraved book in its original cover, and with very fine contemporary hand colouring. Cartographically, it forms a lovely arc with our other nautical material: the portolan (nautical) charts and the terrific Waghenaer Speculum Nauticum from 1586. The Goos also contains a glorious, very well-known “new world map” with beautiful decorations.

You’re really buying at the top end. What is the most expensive item in the collection?

One of the smallest: a portolan atlas attributed to Battista Agnese, which was hand-painted on vellum in c.1550.

But not everything we buy is expensive. Recently I asked the Map House to find some French maps from the late 1600s by Sanson and Duval. They are very pared back and as objects you might think they’re a bit of an anticlimax compared to contemporaneous Dutch maps. But over times French mapmaking took over from the Dutch tradition, and we are interested in rounding out our collection and showing that change.

What is one great discovery you have made?

It is always amazing to think about how these objects have survived, and in such good condition, over so many centuries. One of the greatest discoveries we have made is how many entry points there are into maps and atlases as historic objects: why they were made, what they record and what has been omitted, the purpose they served, how they were made, and by whom. They provide a rich, fascinating lens for looking at our world today and where it came from.

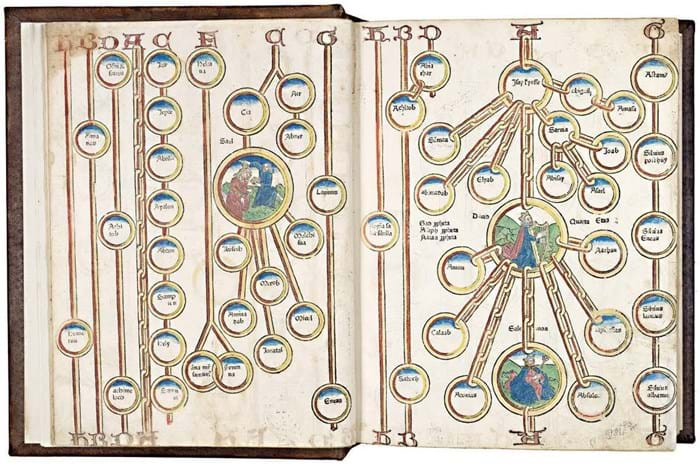

For example, the Rudimentum Novitorum (1475) contains a Biblical history of mankind and is illustrated with not only a world map, but many delightful woodcuts showing people in contemporary dress surrounded by buildings and tools of the period. There are some lovely embellished capital letters in the book as well, which shows the transition from hand-written manuscripts to printing, which was still a relatively new technology.

What is the most unusual item in the collection?

One of the most unusual items is the Cadamosto Codex, which is a portolan atlas hand-painted on vellum. It dates to 1597. This little atlas – just 14 leaves – was commissioned by the Venetian da Mosto family to celebrate their ancestor, Alvise Cadamosto (c.1428-1483), a great explorer and trader. Alvise “discovered” the Cape Verde Islands, and described the Canary Islands and West Africa. From Gambia, he made the first recorded European sighting of the Southern Cross.

The Codex was executed in colour, heightened with silver and gold. Unlike many portolans, which depict the Mediterranean and western Europe, this atlas shows the entire world known to Europeans at the time. The atlas was previously owned by Joseph Brook Yates (1780–1855), a West India merchant, reformer, and collector who was one of the earliest members of the Athenaeum Library in Liverpool; and subsequently by his grandson Henry Yates Thomson, a great collector of illuminated manuscripts.

Do you have a favourite item?

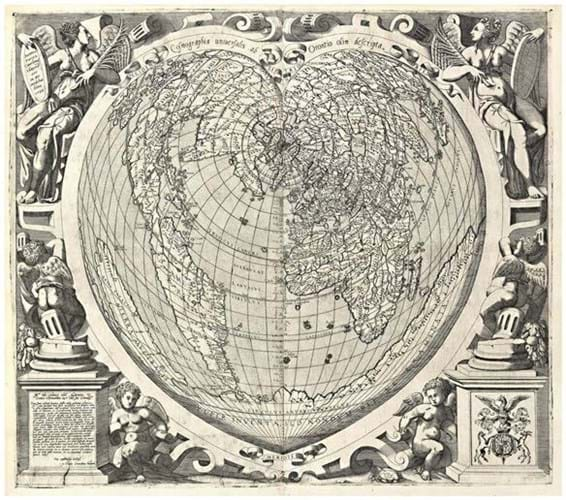

The heart-shaped map by Cimerlino (1634-35) always makes me smile. And the de Jode atlas has wonderfully vibrant colours, and contains a fantastic array of ships, creatures, and vignettes of daily life. On the celestial side, the Cellarius atlas with its glorious engraving, colours and superb little cherubs is just brilliant.

Michele Cimerlino, Cosmographia universalis ab Orontino olim descripta, 1566 49 x 59cm, Verona or Venice.

Do you ever sell items on?

In principle, no. We sell items only if we come across a better copy of something that we already have and decide to upgrade.

What’s in the future for the collection?

We will be adding lots of stories and additional features to Oculi Mundi over time, and we hope to start offering some talks and online exhibitions in due course. We also very much look forward to receiving feedback from visitors, so that we can grow and improve, and be part of an interactive community.

In addition to displaying items digitally, we intend to organise exhibitions and pop-ups, hopefully in collaboration with institutions and other collections that might be interested in exploring topics of mutual interest. We quietly trialed this in the spring, putting 12 maps and 12 atlases on display as part of an invitation-only exhibition.

It was really to see if people were interested, and we were pleased with the response. We love collaborating and are also open to loaning objects from the collection for third-party displays.