It made the sums a little more complicated (many lots incurred an additional 5% import VAT on the hammer price) but it raised the bar in terms of quality.

Both collections – 49 pieces from Robert Bruce Duncan (1943-2019) of Chicago and another 78 lots that were ‘the property of a lady and a gentleman’ – included well-provenanced objects illustrated and discussed in two key books on the subject: Oak Furniture: The British Tradition by Victor Chinnery (2016) and Early British Chairs and Seats 1500 to 1700 by Tobias Jellinek (2009).

The £35,000 Hornby Castle chair pictured on the front cover of this issue was just one of many outstanding examples of Tudor and Stuart seating furniture in the sale. The air is thin at this top level of the market – Bonhams specialist David Houlston estimated around a dozen collectors are currently active – but most lots did match his carefully pitched expectations.

Vindicating the decision to bring them back to these shores, all the top lots sold to UK private collectors.

'Glastonbury' chair

Sold at the lower end of a £30,000-40,000 estimate was a mid-16th century ‘Glastonbury chair’.

The term is believed to have emerged in the 19th century, first used to describe a West Country pegged oak chair in the Bishop’s Palace in Wells that fascinated antiquarians.

According to a carved Latin inscription it was made to remember John Arthur Thorne, the last treasurer of Glastonbury Abbey, who was executed in 1539 amid the turmoil of the Dissolution. They were much copied in the Victorian and later eras but period chairs are rare.

The example here, dated to c.1540-70, once had a carved coat of arms to the back and perhaps ownership initials to the cresting but, for reasons now unknown, both were enthusiastically defaced early in its life. Jellinek describes it as “a very fine and intriguing chair”. The connoisseur collector John Fardon was a previous owner.

The £30,000 bid was the same amount paid for a Glastonbury chair at Bonhams in 2018 and a bid more than the example in the Pelham Olive collection (£29,000 in January 2019). Another Elizabethan seat of this type comes up for sale as part of the Butler collection at Bearnes Hampton & Littlewood in Exeter on March 10.

Stool rediscovered

In Jellinek’s book he pictures a Henry VIII box stool in the Burrell Collection in Glasgow and mentions the existence of another, adding that: “I do not know the whereabouts of this amazing looking stool.”

Both were of a classic mid-16th century ‘five-board’ form but with a hinged top and a sixth board below to form a box.

The provenance of the 'missing' stool dates back to the 1920s when it was part of the collection of William Smedly-Aston (1868-1941), a Birmingham Group artist who owned The Yew Trees, a half-timbered manor house in Henley-in-Arden, Warwickshire.

It was, like many lots in the Bonhams sale, offered here for the first time in more than a generation, selling at the low estimate of £15,000.

Multi-estimate sums were not the norm but strong competition emerged for two pieces, both illustrated in the recent literature.

A James I joint stool from Taunton, c.1620, described by Jellinek as an “example of the extraordinary rare H stretcher formation on an extremely fine and rare stool”, sold at £11,000, while a 17th century ash turner’s armchair from the Duncan collection took £14,000 against an estimate of £4000-6000.

The latter is pictured in The British Tradition where it is attributed to Cumbria c.1640-80. All parts of the chair, including its seat of turned spindle now protected by a later board, were turned on a lathe.

Regional differences

With the foundation of the Regional Furniture Society in 1986, British vernacular furniture has become an increasingly sophisticated subject in which local styles and individual workshops are studied and mapped.

From a UK source was a high-quality Elizabeth I joined walnut and elm open armchair, c.1590, distinctive for its cresting, downswept arms tenoned to turned columns and a parquetry-inlaid panel-back.

Chinnery proposed that similar chairs originated from “an urban centre in the West Country, such as Bristol”. However, London – particularly the environs of Southwark where immigrant German joiners and inlayers lived and worked from the second half of the 16th century – is also a possibility.

This muscular chair is probably that pictured in RW Symonds’ Furniture Making in Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century England (1955) and very close to another featured by Percy Macquoid in The Age of Oak (1925). A former owner was the Bond Street dealer and collector Sir George Hunter Donaldson (1845-1924) whose vast holdings were dispersed in 1925. It sat comfortably within expectations at £11,000.

Country touch of class

For many pieces of this sophistication the generic term ‘country’ furniture is a misnomer. They were probably made for a high-status and urbane audience.

Consider a West Country joined oak livery cupboard c.1580 – a splendid piece with its reeded and palmette-carved ‘cup and cover’ supports and a central panel carved with a lion passant.

From the anonymous US consignors, previous owners included Charles Porter Wilson, chairman of the Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Co (the US grocery chain better known as A&P), whose mock Tudor home The Chimneys on Long Island was built in 1928. Deemed exceptional in terms of form, colour and condition, it tipped top estimate to bring £32,000.

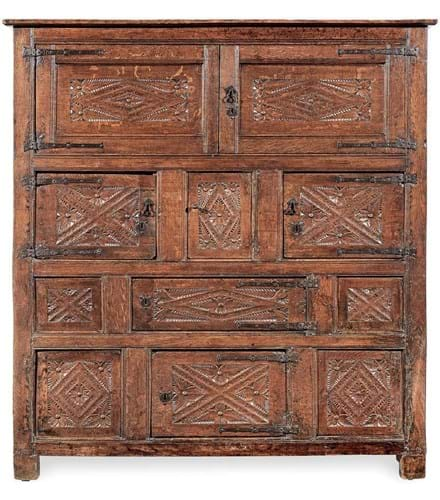

From the same source was a rare joined oak standing cupboard, c.1540. It was previously owned by Kentucky horse-breeder John R Gaines (1928-2005) and later sold by the Blumka Gallery, New York.

Measuring 5ft 2in wide x 5ft 11in high (1.57 x 1.81m), it comprises four registers of doors and panels, each carved with a flower-filled lozenge or saltire. An unusual feature to the sides are three lancet pierced panels to allow for airflow.

Two comparable Henrician ‘Great Hall’ cupboards have been sold by Bonhams in recent years for £60,000 apiece: that from the Adler collection (September 2016) and another from the Olive collection.

This example sold at the lower end of a £50,000-70,000 estimate.

Coffers and chests from the early Tudor period are also scarce. Nonetheless there were several examples in this sale. Among the opening lots was a 3ft 2in (98cm) boarded chest from the first quarter of the 16th century that was carved to the front with a pair of heraldic symbols, a griffin and a unicorn.

Traces of polychrome paint remind us that some pieces of early oak, admired today for their surface and patination, were once boldly coloured. It took £7500 (estimate £2000-3000).

Collecting focus

The focus of these biannual sales is now less on the softer market for furnishing pieces – Georgian kitchen dressers, settles, presses and the like – and more on the small number of survivors that appeal to a serious collecting audience.

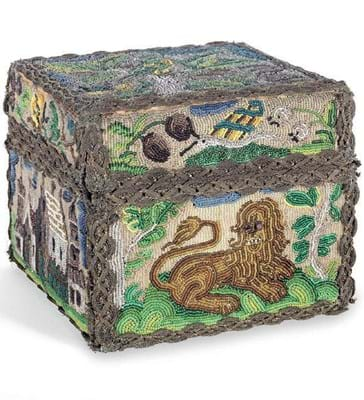

They still include related pieces of vernacular metalwork, textiles and works of art.

Most surviving wooden ‘peg’ tankards are Continental. However, the 7½in (19cm) example here in turned and carved lignum vitae closely resembled English silver and pewter dome-lidded tankards of Georgian period. Repaired early in its life (it probably once had a terminal to the handle), it doubled top hopes to bring £3200.

Small bullet-shaped teapots in pewter are also rare beasts – more common in silver than in base metal.

An example c.1730 with the unidentified maker’s touchmark TB was formerly in the celebrated collection of ‘Bertie’ Isher that was sold by Bruton Knowles in Gloucester in 1976. Back then the teapot sold at £620 (around 10 times the average weekly wage). More than a generation later, it carried more modest hopes of £400-600 and took £700. It is, as they say, a good time to buy.

Sold at £1300 (estimate £800-1200) were two tortoiseshell combs of a type associated with the cottage industry practised in Port Royal, Jamaica, in the decades before an earthquake struck the colonial town in 1692.

The larger of the two combs, at 10in (24cm), carried an unidentified coat of arms using local flora – the kind of faux ancestry often favoured by British settlers in Jamaica. Workshops cutting and engraving the shells of the local hawksbill turtle were run on the High Street by one Paul Bennett and his successor Matthew Comberford.

A spectacular example of the craft, a comb in a case dated inscribed Port Royal in Jamaica and dated 1688, sold for $22,000 at Sotheby’s New York in 2018. Both examples here were missing sections of teeth.