The accepted narrative is that the market for Chinese works – almost unrecognisable from that of 20 years ago when the Asian Art in London festival was launched – has been checked in recent years.

Since the peak of 2011, the handbrake of economic uncertainty and a selectivity that comes with maturity have held sway.

But for those who watch developments through a more focused lens, it is not simply a case of less of the same. As Kate Hunt, Chinese works of art specialist at Christie’s, London puts it: “There is a lot of coming and going in the market. You need to keep a close eye season-to-season on what is selling and at what price level. It only needs a few collectors to push prices up or to bring them down.”

Imperial Rulers

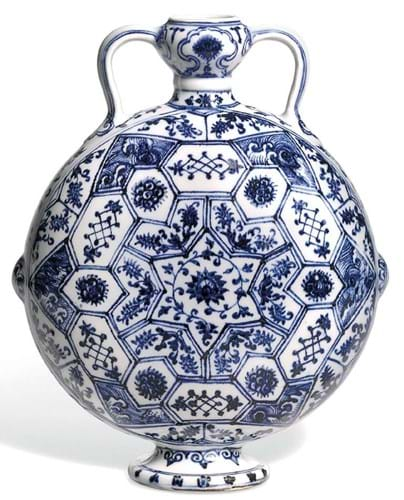

There has been little fall-off in demand for mark and period porcelain. One-off events such as the Pilkington time capsule of Ming blue and white aside, it is imperial wares from the reign of Yongzheng (1722- 35) and his fourth son and successor, Qianlong (1735-95), that continue to set the benchmark.

Representing China’s last great political and artistic flowering, they appeal on aesthetic and emotional grounds. But they also sit well with investment conscious buyers who, in the age of the search engine and dual language catalogue, can make like-for-like comparisons and document profit margins with relative ease.

If anything, investors rather than collectors – including tax-saving corporations and real-estate magnates operating at the highest market echelons – have assumed a more prominent place in the market.

The Yongle (1403-24) blue and white rosewater ewer sold for HK$87m (£8.3m) at Sotheby’s Hong Kong in April 2016. British collector Roger Pilkington (1928-69) bought it from London dealership Bluett & Sons for £5000 in 1967.

John Berwald, a London dealer in Chinese works of art for over 30 years, frames it in simple terms: “The Westernbuyer is fast becoming like the unicorn. Across 30 years I have acquired a good knowledge of Chinese ceramics. I would occasionally like to use it.”

The more subtle advance in Chinese porcelain appreciation has been the rise in status of late Qing and a select group of Republican wares. A collection of Guangxu (1875-1908) yellow and green-glazed dragon dishes and bowls offered by Christie’s Paris in June was typical: low estimates encouraged huge bids for these ‘repeat pattern’ wares that were once dismissed as mere decoration by Western collectors.

Supply remains relatively healthy in these areas: if you missed out in Paris, there will doubtless be others to buy with your hard-earned RMB in Hong Kong, in Germany, in the UK and in the US.

“It only needs a few collectors to push prices up or to bring them down”

Kate Hunt, Chinese works of art specialist, Christie’s

Kate Hunt of Christie's.

Demand for Republican porcelain is focused around a more select group of named artists. Pieces by the ‘Eight Friends of Zhushan’ and their students will today regularly outsell the best Transitional blue and white porcelains that had proved so attractive to the first wave of Mainland Chinese collectors.

From a slower start, pedigree items from the Song (960-1279) have seen significant uplift.

A generation ago it would not have been uncommon to hear such understated pieces described as ‘Japanese taste’. However, as the great Japanese collections assembled from the early 1970s are now slowly dispersed, these early wares are returning to Hong Kong, mainland China and Taiwan – not all of them the poorer cousins of Qing magnificence.

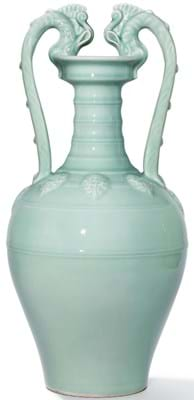

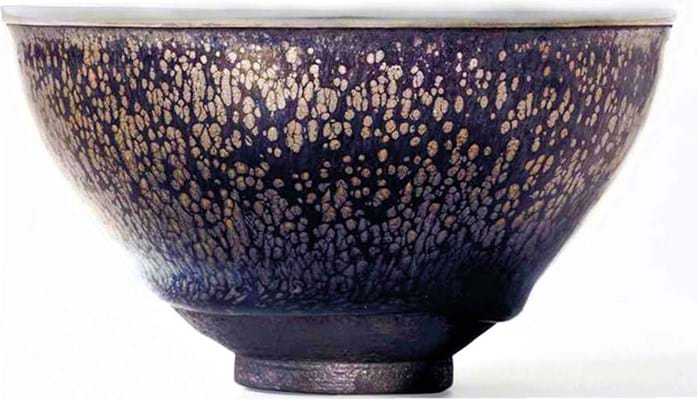

The celebrated Kuroda family Jian tea bowl was the prized lot of the Linyushanren collection selling in New York at $10.3m (£7.9m). An 11th century celadon brush washer from the fabled Ru kiln in Henan – one of only four Ru wares in private hands – is expected to surpass that sum at Sotheby’s Hong Kong on October 3.

Selling the best Yuan and Song ceramics in Hong Kong rather than London or latterly New York represents a relatively new development – one that Colin Sheaf, chairman of Bonhams UK and Asia, and head of the auction house’s Asian art department, says “reflects the emergence in mainland China of an older Beijing-influenced taste for the classic early, non-excavated, imperial wares”.

Still lagging behind are export wares of all types and the often splendid pottery sculptures from the Western Han and the Tang periods.

Sheaf doesn’t expect any great change. “Export art still only really appeals to Western buyers – the market is solid but has not really moved much in years. Archaeological art is increasingly affected by buyers demanding a secure provenance, before the key 1970 UNESCO date. Prices can be high for the finest archaic works but it’s not a predictable market to price.”

This robustly modelled bronze buffalo, typical of Western Zhou (1046-771BC) sculpture, sold for $600,000 (£450,000) as part of Sotheby’s Important Chinese Art Sale in New York on September 13. Provenance is increasingly important in the sale of archaeological material. This 10½in (26cm) model was part of an exhibition titled 'Ancient Chinese Bronzes' held by Yamanaka & Co, London in 1925, and was later in the collections of both Mary Cohen and JT Tai. Previously it had sold at Sotheby’s New York in 2011 for $110,000. A number of buffalos of this type are recorded and are believed to have been used as stands or feet to support large vessels.

Micro Markets

The die is cast in terms of the relative popularity of the different categories of Chinese works of art. Relative to Ming and Qing imperial porcelain, other areas of the applied arts can appear under-priced.

The greatest pieces of cinnabar lacquer from the late Yuan or early Ming period are among them. A little of that disparity has been redressed at recent sales but serious collectors are still relatively few in number.

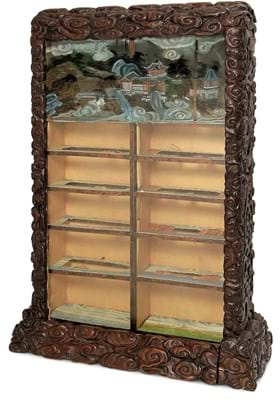

Classical furniture from the Ming and early Qing – plus associated works of art in zitan and the fragrant aloeswood – is on a quicker roll.

A series of single-owner collections have ‘white gloved’ including that of Dr SY Yip (Sotheby’s Hong Kong) and Robert Ellsworth (Christie’s New York). A set of four Ming huanghuali horseshoe back armchairs, pictured in Ellsworth’s 1971 publication Chinese Furniture, Hardwood Examples of the Ming and Early Ch’ing Dynasties, was taken to $8.5m (£6m).

Across its autumn sale week, Sotheby’s Hong Kong will conduct an exhibition of the so-called MQV collection assembled by dealer Grace Wu Bruce. The Best of The Best: The MQJ Collection of Ming Furniture will be on public view with a book of the same title. The collection is apparently not for sale – yet.

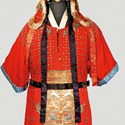

Following a spike in demand for the embroidered silk robes and other paraphernalia associated with the Qing court, textiles have become a more recognised and predictable collecting category. Meanwhile the series of sales of the Bloch snuff bottle collection have underlined the possibilities of micro-markets when the conditions are right.

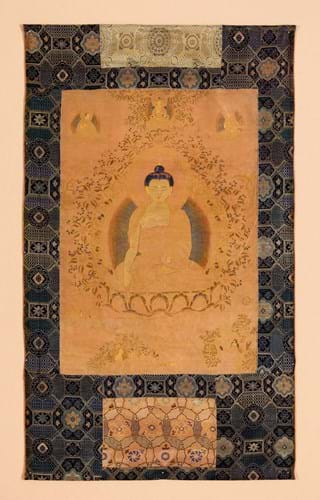

The sale of the Jongen-Schleiper collection at Bonhams Bond Street in May was another sell-out and set new price levels for later Tibetan thangka paintings. However, these aren’t market revolutions: the Jongen-Schleiper auction was dominated by just a few aggressive buyers taking the chance to buy a coherent, well-preserved and superbly-researched group.

A rare 18th century distemper and gold on silk thangka of Ratnagni Buddha that sold for £255,000 (estimate £20,000-30,000) as part of the sell-out Jongen-Schleiper collection at Bonhams on May 11. This thangka, once part of a set devoted to the previous lives of Shakyamuni Buddha, included an extensive Tibetan calligraphy on the reverse detailing the donor as Rinchen Ngodrub, who lived in the Upper Mu region of Tibet.

The consensus among the UK trade is that jades – even the pale, monochromatic colours that are deemed ‘Chinese taste’ – are softer than they were four or five years ago. Keen pricing, in addition to the usual variables of provenance and quality, is now key. One of the Critchel House jades, the famed group of Chinese hardstones bought half a century ago by a titled Dorset family, returned to market this year. The large celadon carving of a water buffalo sold by Woolley & Wallis for £340,000 in 2010 was offered at Sotheby’s Hong Kong. It failed to sell at a punchy estimate of around £800,000.

As Hunt says: “There is great strength in the market but it does depend on what you are selling.”

“Export art still only really appeals to Westerners - the market is solid but hasn’t moved that much”

Colin Sheaf, Bonhams

Confidence Sapped

A major factor in the fall-off in jades has been the preponderance of fakes. Copies and homages have been part of the Chinese tradition for centuries. However, 21st century price levels have prompted the trickle to turn into a flood.

Many of the current crop of fakes are extremely good, exhibiting only small differences in gilding, carving, enamelling, potting and paste than from original works of art. Confidence is being sapped across many disciplines with some, such as scroll paintings and calligraphy (the largest Chinese art category, with more than 100,000 lots sold in mainland China alone last year) now fraught with issues of attribution and authenticity.

Catalogues raisonnés are desperately needed for some artists but these are relatively young markets and scholarship is yet to catch up.

Prices for once booming contemporary works are now correcting – by as much as 40% in some areas. The speculative market in Hong Kong and Beijing, where pictures by living artists are regularly traded for more than the price of downtown apartments, has been hardest hit. It might urge the abundance of 20-somethings operating across this roller-coaster field to think again.

Certainly this is not a market without challenges. New laws relating to the sale of items ‘of cultural history’ are prompting some German auctioneers to sell Chinese art outside Germany. Ivory and rhino horn works of art come with increasingly amounts of red tape while issues of non-payment refuse to go away. Suggestions in the recent Global Chinese Art Auction Market Report 2016 that the market in mainland China and Hong Kong had grown to $4.8bn were countered by the small print (see page 5). Just 51% of items were paid for – a figure that dropped to 47% for top priced items.

Chinese auction houses are keen to tackle the problem – different coloured paddles now denote varying levels of bidding ‘power’ – but it is enormously difficult to extract money from a buyer who chooses not to fulfil a saleroom promise.

Emptying the Attic

The preponderance of fakes highlights a wider issue of supply after a decade of sell, sell, sell. “You can only empty the attic once,” says Berwald.

Buying opportunities still abound across the thousands of lots offered on a monthly basis, but sales are thinning. Even spectacular discoveries like the £13m butterfly vases sold by Christie’s in May (page 38) can’t paper over this crack.

In 2016 the total sales value of Chinese art and antiques sold overseas declined by 27% year-on-year to $1.9bn, according to the Global Chinese Art Auction Market Report 2016. “Supply is dwindling”, says Sheaf “and it’s accentuated because demand is now global, internet-driven and the better items are becoming almost untraceably dispersed.”

It has been the strength of the Western market in particular that buyers come in expectation of finding honest items from old collections at relatively low prices.

Few auctioneers care to admit it but, under pressure to perform as before, a rising percentage of material sold in Europe and the US now comes from sources across the Far East.

“There are still those collections out there formed in the 1920s-50s. You just need to fight harder to get them”

John Axford, Woolley & Wallis

John Axford of Salisbury saleroom Woolley & Wallis.

John Axford, director at UK regional auctioneer Woolley & Wallis in Salisbury, admits “keeping the sales clean can be a challenge” when so much being offered over the counter comes without the credible provenance buyers demand.

“People want genuine goods – and ideally they want to buy them at auction. But the attempt to fill the void of diminishing supply is bringing too much problematic material onto the market.”

But Axford is no doom-monger. His department now has five full-time staff members – including new recruit Jeremy Morgan who joined in August after more than 20 years at Christie’s. “I remain confident we will still be here in ten years’ time. There are those collections out there formed in the 1920s-50s. You just need to fight harder, travel further and negotiate more strongly to get them.”

Sheaf, too, is confident of longevity. “Chinese art is now more global than almost any other area of the art world except contemporary art and jewellery. If the market changes, it will be because some established dealers and collectors become less hungry, not because new geographical areas of buyers suddenly emerge.”

Market Maker

If global economics is the ultimate market maker, then what of the plethora of other different mediums, styles and cultures that make up the umbrella term ‘Asian art’?

There’s no doubt that centuries of artistic endeavour have been left behind in the rush to sate the Chinese appetite. Jonathan Tucker, dealer in early Indian and South East Asian sculpture, contrasts the abundance of university graduates operating across the Chinese art market with the absence of young blood in his chosen field. “Christie’s and Sotheby’s stopped their sales in London almost 20 years ago,” Tucker observes.

Interest from the nouveau riche of the Indian subcontinent is currently focused on the modern and contemporary market. A much deeper art history with a rich seam of Pahari, Company and Mughal School painting and Gandhara sculptures is waiting to be tapped.

Korean Uplift

There has been sufficient Korean bidding of late to suggest an historically volatile market is strengthening once again.

“The Korean market has been up and down,” says Axford, recalling the extraordinary moment 20 years ago when a Korean vase could outsell its Chinese exemplar. Woolley & Wallis recently sold a consignment from the Kensington home of the late collector John Newall with all 21 Korean works of art sold including a huge price posted for a suit of armour.

Museum building in South Korea is a current and positive influence.

There are also Western collectors who have been turned off the frothy Chinese market and turned on to the creativity and spontaneity of Japan. However, the accepted wisdom is that this is still a buyer’s rather than a seller’s market, at least for the 19th and 20th century export-quality art that dominates sales in London and New York. Export restrictions that forbid the movement of a sublime ivory okimono or netsuke to keen collectors in the US add a grey cloud.

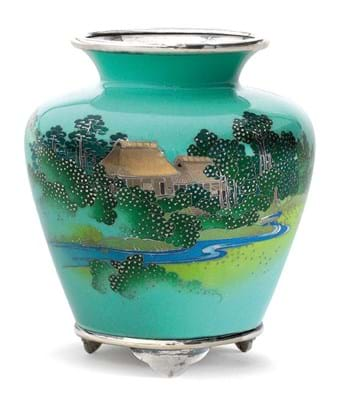

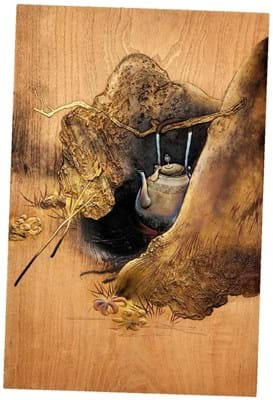

The exceptions are two-fold. The demand for a small number of Meiji masters – the miraculous cloisonnés of Sosuke, Yasayuki and Kodenji or the lacquerwork of Shibata Zeshin – transcends any wider softness in the market. The Edward Wrangham collection of Edo and Meiji sword fittings and sagemono offered in five parts at Bonhams since 2010, is ample proof of the old adage that quality sells.

There is also the knowledge that much of the finest classical Japanese art is still sold discreetly in Japan. Ultimately, Sheaf says, “trying to judge the strength of the Japanese art market from the evidence of Meiji art sold in the West is rather like judging the Chinese market by following the prices of armorial dinner services”.

In numbers

51%

Defaulting buyers at auction remain a chronic problem in mainland China and Hong Kong, with payment rates dropping to 51% in 2016.

324

The number of overseas auctioneers offering Chinese art and antiques for sale in 2016 fell from 332 in 2015, marking the first decline in seven years. The number of lots offered and sold also dropped for the first time since 2012.

21%

The share of Chinese art and antiques sold in North America and Europe dropped from 33% in 2011 to 21% in 2016. The market is becoming concentrated towards Asia, as major auction houses shift their inventory to Hong Kong.

Source: The Global Chinese Art Auction Market Report 2016, published by Artnet and the China Association of Auctioneers