The evening auctions at Sotheby’s (25/20/12.5% buyer’s premium) and Christie’s (25/20/12% buyer’s premium) totalled £82.81m from 116 lots on July 5-6. This was a superior sum to last year’s equivalent sales, especially at Sotheby’s, which dramatically improved on a lean £13.8m contribution.

Overall, Sotheby’s larger 70-lot sale was the stronger of the two, with an 85% selling rate (the house’s best ever for an Old Master evening sale) and a £44.9m hammer total.

Alexander Bell, co-chairman of Old Master paintings worldwide, said after the sale that the total numbers of bidders and countries were “significantly up on last year’s sale” and, as well as fresh-to-the-market works, an appetite also emerged for ‘seen’ works.

Christie’s slimmer 48-lot sale the night after totalled £37.8m from 36 lots (75%). It was down on last year’s total, which included the £40m Rubens Lot and his Daughters, but for the second year in a row, Christie’s could claim the bragging rights on selling the highest-priced picture – a £23.25m view of the Rialto Bridge by Guardi (see News, ATG No 2300).

In all, this was good reading for a sector that has come under pressure in recent years from the high-flying fields of modern and contemporary art.

These areas have found it easier to draw in collectors, offering potentially high returns, the seemingly unending supply of fresh works and record-breaking sales.

One solution to counterbalance this trend was to up the ante on marketing for this series of Old Master sales. Slick videos, some using CGI and animation, are new to the sector’s promotional arsenal.

Such marketing exercises may not directly attract new buyers, but their use in an increasingly media-friendly and Instagram-hungry world will surely help.

Another aspect of this series was the abundance of fresh works, the perceived lack of which has conventionally been a sticking point.

Over half of Sotheby’s lots had either not appeared at auction before (40%) or were being sold for the first time at auction in over 50 years (18%).

Both evening sales also set 13 artist’s records.

The quality of the material offered and the sums fetched led to suggestions that London has reasserted itself as the premier Old Master location, especially with Christie’s moving away from the traditional major January sales in New York. But this seems premature for a market where results can easily be skewed by single lots.

The top-sellers at both auction rooms for instance – the impeccably preserved Guardi Rialto Bridge view and Turner’s £17m German canvas of the ruined fortress of Ehrenbreitstein (discussed in ATG No 2300) – amounted for almost half the entire totals for both evening sales.

Sotheby’s

One of the most intriguing portraits of the week was a recently identified work of Anne of Hungary’s court fool, Elisabet, by Jan Sanders van Hemessen (c.1504-56).

Last appearing at auction in 1814, it shows an amused old woman wearing a gown of vivid green and yellow, a matching pointed hat and an unusual arrangement of rings around her neck (perhaps a link to some magic trick).

The work, which in years gone by may have passed under the radar, chimed with today’s taste for the quirky and appealed to more than just Old Master collectors.

George Gordon, Sotheby’s worldwide co-chairman of Old Master paintings, said “our clients are not worried by the weird” and are “less concerned with art matching their sofas”.

Against a £400,000-600,000 estimate, the 19½ x 16in (49 x 40cm) oil on oak panel sold to a phone bidder at £1.8m after a lengthy battle with an internet bidder.

Another strong price was fetched for a rare grisaille by Sir Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641). Depicting the Flemish engraver Jean-Baptiste Barbé, the small 9¼ x 6½in (24 x 16.5cm) oil on panel made £1.35m. This was well above hopes of £200,000-300,000, and probably more than the vendor had paid for it at dealer Agnew & Son in 1998.

Indeed, Van Dyck was one of the most prominent artists of the week. Two more works by the artist appeared at Christie’s the following night: a newly discovered oil of St Sebastian that sold within estimate at £1.6m (the Louvre owns another version) and an oil on paper head study of an old man from van Dyck’s first Antwerp period, which sold over estimate at £95,000.

Elsewhere at Sotheby’s, a newly discovered study of an old woman by Sir Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) sold within hopes of £300,000- 500,000 at £340,000.

The 20 x 16in (50 x 40.5 cm) oil on oak panel sold for $27,000 (£18,620) in March last year, catalogued ‘as studio of Rubens’ at Wechslers in Washington DC. Sotheby’s had sought approval from the Rubenianum in Antwerp, which studied it first-hand.

Another indication of the health of the market came when Ecce Homo by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1617-82) reappeared in the saleroom.

The vendor broke the record for a Murillo when they acquired the work from Christie’s in 2005 for £2.2m.

Returning relatively quickly to auction, it was hammered down at Sotheby’s at £2.3m – a new record for the artist, although the vendor probably made a loss when fees are taken into account.

Christie’s

Like Sotheby’s, Christie’s had several pictures returning to the market after a short time.

One was The Minuet by Giandomenico Tiepolo (1727-1804), a 13 x 20in (33 x 50 cm) oil on canvas of a group of elegantly attired Venetians dancing in the countryside estimated at £1.5m-2.5m.

Back on the auction block after a good clean, it easily bettered its 2007 premium-inclusive price of £1.3m (also at Christie’s), selling for £2.6m.

Elsewhere in the sale was an ‘estimate on request’ portrait of a bearded old man attributed to Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (1606-69).

Bidding opened at £950,000, and drew competition between a phone bidder and Old Master dealer Johnny Van Haeften. It was knocked down to the former at £1.75m.

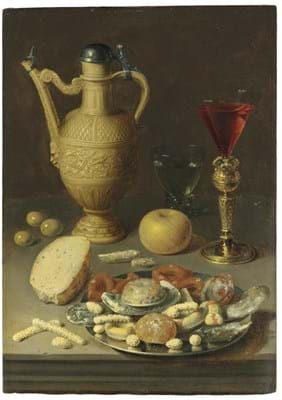

Earlier in the evening, Van Haeften had triumphed over a phone bidder to secure a still-life painted by the rare and enigmatic artist David Rijckaert II (1589-1642) at an above-estimate £460,000.

Consigned from the property of ‘an important European collection’, it was a hitherto unpublished work and deemed an exemplary example from among the first generation of Flemish still-life painters with its ‘incisive detailing of objects and illusorily subtle composition’.

However, Van Haeften appears to have other ideas about the attribution, telling The Telegraph: “It’s not Rijckaert; it’s Osias Beert.”