1. Tiffany pendant – £10,000

Sapphire mining at the Yogo Gulch in Montana began in 1895 after a cigar box of pale blue gems picked from a creek by a local rancher found its way to Tiffany’s in New York. There an appraiser pronounced them “the finest precious gemstones ever found in the United States”.

Gemstones found on North American soil – tourmalines from the state of Maine, North Carolina moonstones, Mississippi freshwater pearls and sapphires from Montana – were all favourites of Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848-1933).

George Frederick Kunz, head of gemmology at Tiffany at the time, supplied the raw materials and fuelled a fascination for unusual and unconventional stones in contrast to the platinum, diamonds and natural pearls that had made ‘white’ the dominant colour of the Belle Époque style.

A good example of Tiffany’s Arts and Crafts colour palette came for sale at Lyon & Turnbull in Edinburgh on September 20. This, moonstone and sapphire pendant, dated to c.1915, had a guide of £2000-3000 but raced away to bring £10,000.

2. 18th century flagon – £7000

English stoneware flagon made for the Angel Inn in Colnbrook, Buckinghamshire, £7000 at Woolley & Wallis.

The sale of British and Continental Ceramics and Glass at Woolley & Wallis in Salisbury on September 19 included items from the collection of the late Jonathan Horne. For many years he was the UK’s preeminent dealer in early British pottery.

Several modestly estimated lots from Horne’s estate raced away, including this large English stoneware flagon. Applied with a plaque of a winged female figure or angel, it is an inscribed and dated piece, incised Hen Hosey 1723.

It was only after the catalogue was published that he was identified. The Hosey family were proprietors of the Angel Inn in Colnbrook, Buckinghamshire from the middle years of the 17th century with Henry Hosey recorded in a sale to Richard Bullock dated 1733. The 18in (45cm) pear-shaped bottle would have sat on the bar of the Angel Inn and dispensed ale or cider to visiting customers.

Estimated at £400-600, it attracted fierce bidding both in the room and on the phone, eventually selling to a determined American buyer for £7000.

3. Chaumet diamond necklace – £240,000

Bonhams’ London Jewels sale on September 21 was topped by this Chaumet diamond necklace. It was knocked down at £240,000 against an estimate of £120,000-150,000. Made around 1900 the striking design is one conceived in 1896 when the firm was commissioned to make a tiara for the Archduchess Maria Dorothea of Austria (1867-1932) for her wedding to Philippe, Duke of Orleans. The first version, noted for having 'inverted arches interspersed with laurel-leaf elements supporting large diamonds in tapered openwork mounts' was convertible to a necklace. Such was the design's popularity that several slightly different versions were made. This is one of them and a rare survivor.

Mounted in silver and gold, signed Chaumet Paris, it includes old brilliant and table-cut, cushion and pear-shaped diamonds with a total weight of approximately 32ct.

Other jewels were made by Chaumet incorporating similar 'floating laurel leaves'. At the 1900 Paris Exposition, the jury noted Chaumet's technical mastery and how his elegant jewels were carefully designed to enhance important gemstones.

4. Ann Forbes self portrait – £9000

While the Dundee-born painter Catherine Read (1723-78) is considered the first Scottish women to work as a professional artist, a close second was Ann Forbes (1745-1834). Born in Inveresk, East Lothian, the granddaughter of the portrait painter William Aikman (1682-1731), Forbes demonstrated remarkable talent and determination to further her artistic education in Italy at a time when female artists were excluded from the training given to male students.

Tutored in Rome by the ex-pat Scottish artists Gavin Hamilton and James Nevay, she returned home in 1771 as a competent oil painter and opened a short-lived portrait studio in the cut-and-thrust of Georgian London. Poor health forced her back to Edinburgh, but she recovered and made a living in the city as a drawing teacher and a portraitist.

Forbes’ likeness is best known through a 1781 painting by her friend David Allen (1744-1796) that hangs in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery. There she is shown in an embroidered white shawl working at the easel, her gaze turned away from the viewer in steely determination.

The 21 x 18in (52 x 41cm) self-portrait offered by Cheffins in Cambridge as part of a two-day sale on September 20-21 showed Forbes in a similar guise. Worked in the artist’s favourite medium of pastels on paper, she is again shown holding portfolio and the porte-crayon used by many Georgian artists.

Former owners of this picture included the eminent British rower and Olympian Frederick Pitman (1892-1963) and the British journalist and Reuters manager Sir Christopher Chancellor (1904-89). However, at a moment when female artists of all eras are being reassessed, its commercial value has probably never been higher.

Estimated at £800-1200, it was knocked down at £9000 (£10,580 including 24.5% buyer’s premium).

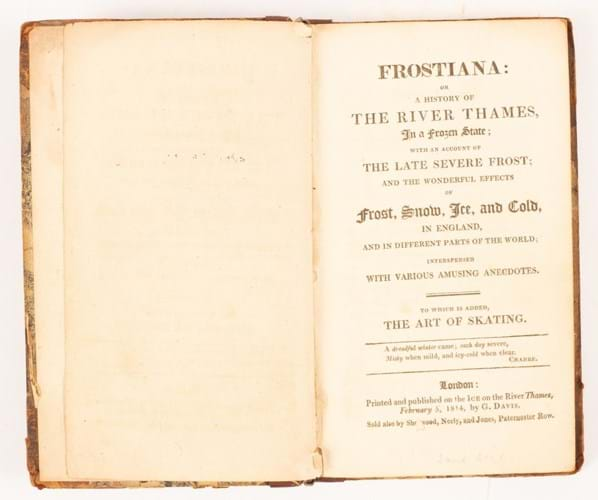

5. Frostiana book – £1700

The books sale at Chorley’s in Gloucestershire on September 19 included a copy of Frostiana: Or a History of the River Thames in a Frozen State. It was published in 1814 during what would be the last ever London frost fair.

As had happened a few times before in previous centuries, in December 1813 (the bitter winter of Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow) ‘Old Father Thames was taken into custody’ by the cold and for close to six weeks (from December 27-February 5) merchants had set up booths on the thick ice to sell food, drink and souvenirs.

Among those looking to make a quick shilling was the Paternoster Row printer George Davis who printed at least some part of this diminutive 124-page guide (perhaps the title page or a quire) while on the ice. It is dated February 5, 1814, the last day of the fair by which time the river ice was beginning to break up.

The book amounts to a written history of London's frost fairs, interspersed with anecdotes, humour and practical advice on topics such as ice cream making and figure skating. Priced at three shillings it was on sale at a number of London bookshops for much of the following year. As all the copies that survive appear to be first editions, it was seemingly never reprinted.

While the text is well-known through digital editions (the final chapter The Art of Ice Skating is one of the earliest works on the rules of figure skating), the book only rarely appears for sale today.

In 2018 a worn copy in a later binding sold for £250 at Roseberys. Chorley’s copy, guided at £80-120 took £1700. One of 14 lots from the estate of the late Diana and Gospatric Home of Lily Farm, Buckinghamshire it had the bookplate for Gordon Home of Vanmoor, Hambledon, Surrey.

Eight frost fairs were held on the Thames between 1607 and 1814, taking advantage of the firm ice that formed on the river as it flowed slowly in the shallows near the 18 arches of Old London Bridge. The winter of 1813-14 was the final fair as by 1831 a new bridge of just five stone arches had been built and the medieval structure was demolished.