By the late Victorian era virtually every large village in the UK had a resident 'professional' taxidermist and almost every home a stuffed bird or mammal of some description. And interest in the natural world, the advent of foreign travel and the lure of big game hunting before the era of animal conservation ensured the industry thrived into the 1930s.

By the 1970s of course, taxidermy had entered its fashionable nadir, and most of the commercial companies had ceased trading completely, but it was not forever. In the past two decades, there has been an undoubted resurgence of interest in mounted specimens from the animal kingdom as serious antiques, and taxidermy is among the most searched-for items on the-saleroom.com

What Do People Collect?

Collectors of antique specimens prefer named cases by the best makers. It is not an exhaustive list but the best examples of antique taxidermy often carry the labels of Henry and Rowland Ward of Piccadilly, James Hutchings of Aberystwyth, James Gardner of London, Thomas Gunn of Norwich, A.S Hutchinson of Derby, Jefferies & Sons of Carmarthen, Murray of Carnforth, H.T. Shopland of Torquay and Peter Spicer of Leamington Spa.

A large cased diorama of African birds from c.1865-80 with a trade labels for one of the most renowned 19th century London taxidermy firms: Ashmead & Co, Naturalists, 35, Bishopsgate. It comprises a pair of Secretarybirds stood above a coiled snake prey to the centre, a Northern Black Korhaan stood upon a faux rock ledge above, and a Cape Crow to the left perched upon a lichen and moss encrusted branch, all mounted amongst faux rock work, ferns, tall grasses and fauna, set against a painted evening sky back board. It sold for £12,500 at Tennants in July 2018.

There are equally respected European firms, while Van Ingen & Van Ingen of Mysore were renowned for their big game mounts (particularly tiger skins). Most taxidermists have a distinct style in case production: those by James Gardner for example are distinctive for their brightly coloured gouache or watercolour backgrounds, Peter Spicer for exceptional cabinetmaking.

A word of warning. Some of these firms produced taxidermy cases on an industrial scale (a factory production line was not uncommon) and all were capable of mediocrity as well as excellence. The allure of a maker's name has also led to forgeries. It is not unusual for a routine example of Victorian taxidermy to be 'rehoused' in an empty case with a trade label or for the ivorine label of Rowland Ward to appear on a previously anonymous big game head. It is important to seek expert advice when purchasing higher value taxidermy by famous Victorian makers.

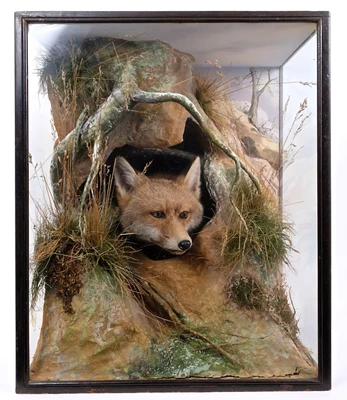

Collectors of antique taxidermy are as discerning as any others. There is no market for the moth-eaten red fox mounted by an anonymous Edwardian amateur. The key components of a desirable 'mount' are condition, maker, case, species and subject.

Condition is key. 'Mothed' is the collector's term for insect attack that has caused irreparable damage. Ideally taxidermy should be kept at an ambient temperature, out of direct sunlight and subject to pest control. Sadly that is not always the case and the high cost of professional restoration (often significantly more than the item's commercial value) dictates that only a small percentage of antique specimens are worthy of preservation. It is always preferential to have the case sealed and in its original condition.

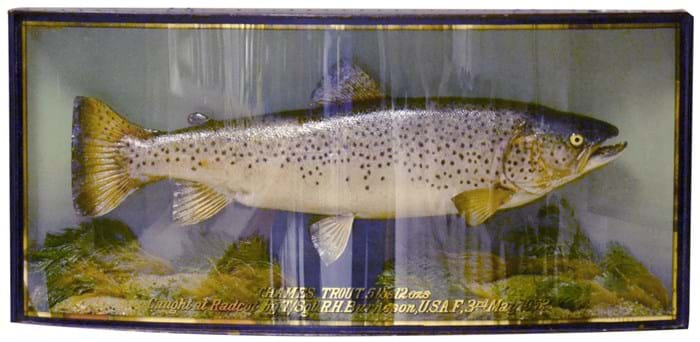

For many years the acceptable face of taxidermy collecting was cased fish - gentleman's trophies of the ones that didn't get away. A number of firms undertook fish taxidermy (including Rowland Ward and Peter Spicer) but the finest and most prolific exponent of the craft was John Cooper & Sons of London.

Many have survived (mounted fish suffer less from insect attack) so there is a definite collecting hierarchy. The cases that are most sought after these days are bow-fronted (they show the specimen off in the best possible way and give a greater impression of water in the case). It is always desirable to have an inscription in gold leaf denoting the species, the weight and the date and place of capture - and particularly if the specimen happens to be a record-breaker or an unusual catch. Pike, trout, bream, tench, roach, rudd and perch are the most common but Arctic char, bleak and salmon are scarce and command a premium.

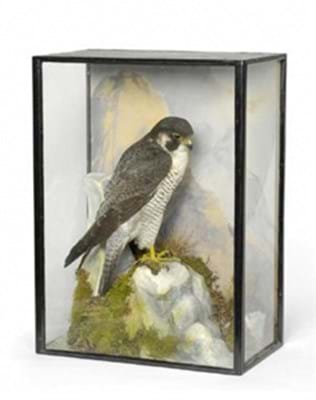

Even a deluxe firm such as Peter Spicer produced in large numbers mounts of then common species (fox, hare and otter masks and the like) over the years. The more exotic or impressive the species the more interest it is likely to generate. At the extreme end are specimens such as the now extinct thylacine or Tasmanian wolf cased by Murray of Carnforth that resides in the Kendal Museum, Cumbria or more than 80 surviving examples of the great auk (last sighted in 1844).

Most collectors prefer cased birds and mammals that show the subject matter as close to how it existed in the wild. A curious but avidly-collected niche of the Victorian taxidermy output are the anthropomorphic 'tableaux' depicting groups of animals taking part in human activities. Squirrels in classroom settings, kittens at weddings and frogs fighting duels, are undoubtedly macabre but appeal to a dark sense of humour and must be judged in the context of the era in which they were created.

Walter Potter (1835-1918) was the leading exponent of this kind of taxidermy. His Victorian museum in the village of Bramber in West Sussex was a famous tourist attraction for many years. Its contents (including the celebrated tableaux The Death and Burial of Cock Robin) later moved to the Jamaica Inn on Bodmin Moor before they were finally sold by Bonhams in September 2003. That this landmark sale included four-figure sums for preserved specimens of animal 'freaks' underlines that these too have a market - particularly in the USA.

Taxidermy And The Law

Old taxidermy doesn't escape the laws governing the sale of "parts and derivatives" of endangered species. Most taxidermy does enjoy an exemption from the controls under the "worked item" derogation and can usually be restored (or rehoused in a new case) without affecting its antique status. Providing the repair is done without the use of another CITES species, this comes under permissible maintenance (see Essential Info).

However, certain UK species (some reptiles and butterflies) will still require an individual CITES licence regardless of when they were mounted, while the eggs of native European birds are also protected under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 and may not be sold. Likewise any international trade in antique specimens (trade outside of the EU) will require export and import licences if listed as a CITES species regardless of when it was mounted.

The Market

Taxidermy is no longer the preserve of a small group of dedicated enthusiasts or the anglers who have long admired the skills of John Cooper. The fashion for the exotic has fuelled demand from interior decorators, while the recognition that the best taxidermy combines excellent technique with artistic flair and good cabinetmaking skills has brought nto the fold of the mainstream antiques trade.

The resurgence of interest in taxidermy has seen the advent of specialist sales (with related natural history specimens) at Tennants of Leyburn and a healthy section at Bonhams' Gentleman's Library sales but good individual specimens and occasionally single-owner collections can appear for sale anywhere.

A late 19th century cased diorama featuring a group of humming birds under a 17in (44cm) glass dome. It sold for £3000 at Summers Place Auctions in Billingshurst, West Sussex, in September 2018.

In recent times the market has been dominated by the huge prices paid by Far Eastern bidders for rhinoceros horn. Changes to legislation have curbed the sale of mounted horns in the UK although complete rhino heads are still permissible.

The highest prices tend to be paid for the 'big beasts'. A 10ft 2in (3.1m) long tiger skin in exceptional condition sold for £14,500 at Christie's South Kensington in September 2009. There is also heavy demand for the most sophisticated displays such as the elaborate carved walnut cabinet of exotic birds marked for Henry Ward sold to a North American collector for £8000 at Clevedon Auctions of Bristol in November 2011. This substantial sum came after a year when prices for more typical mounts (including Cooper fish) had, by and large, been falling.

Further Reading

A History of Taxidermy: Art, Science and Bad Taste by Pat Morris. ISBN 0956487319

Walter Potter and his Museum of Curious Taxidermy by Pat Morris. ISBN-10: 095455969X

Van Ingen and Van Ingen: Artists in Taxidermy by Pat Morris. ISBN 10: 0954559630