Sporting pictures might not be the strongest area of the art market at present but when a work has the ‘right’ subject matter or date this can go a long way to generate interest.

When it comes to cricketing scenes, historical elements often count for more than artistic quality.

Although paintings of a particular player, match or ground are sometimes what buyers look for, when it comes to more generic or unattributed cricketing scenes, the date of the work is often the main determinant of value. Naturally, it is a case of the earlier the better.

Dating such scenes is not always an exact science, however. Many works from the 19th century and earlier were unsigned and undated and so specialists need to look for clues within the paintings themselves such as the equipment used and attire of the players.

Unidentified in Kent

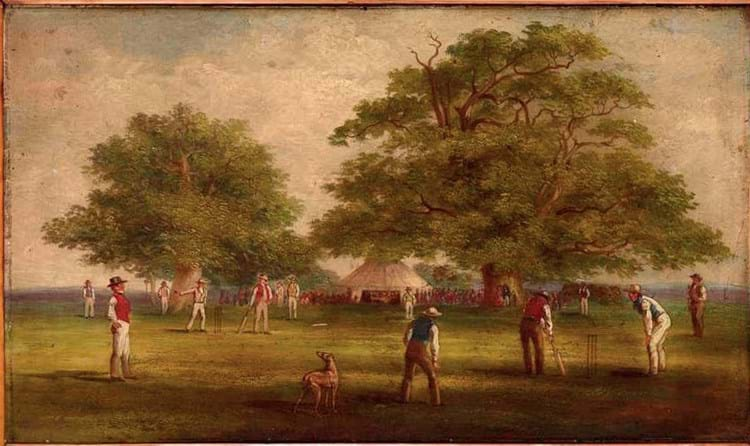

A picture that turned up at Lyon & Turnbull’s (26% buyer’s premium) February 22 auction in Edinburgh posed a few puzzles. The 17 x 28in (43 x 71cm) oil on panel depicted a village cricket match but came with no documented history. It was consigned by a private vendor with only a suggestion that it depicted a match taking place in Kent.

While the artist was unknown and no candidates could be established, a few pointers helped determine its approximate date. The use of oblong bats indicated a post-1770 date as, until then, cricket was played with a curved bat that looked more like a club or hockey stick.

The fact that the wickets comprised three stumps here also meant an 18th century date was unlikely – two stumps and a single bail was the standard practice during that period.

The bowler was bowling underarm, implying that the match was played before 1860, by which time the practice had effectively disappeared and was replaced by the overarm action. The players’ clothing meant the likely date could be narrowed further as, from the 1820s, the kind of looser trousers as seen here had become the norm.

One other feature was significant. The position of the fielders in the background indicated that the trees were either used to define the boundaries or they may even have been inside the boundaries themselves.

Three examples of trees within the boundary in cricket are known, the most celebrated of which was the ‘St Lawrence Lime’ at Canterbury Cricket Ground – a tree that measured 90ft (27m) high in 1847 and remarkably lasted until 2005 when it eventually blew down. The other two examples are both overseas grounds: City Oval in Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, and the VRA in Amstelveen in the Netherlands.

The L&T catalogue stated that Kent County Cricket Club were unaware of the picture and were ‘doubtful’ that it was a Kent subject. But, even without being able to pinpoint an exact location, the picture still had appeal as a piece of cricketing history.

It was offered as ‘English School c.1830’ and estimated at £6000- 9000. The auction house reported ‘a range of interest’ as it drew considerable competition on the day. It was knocked down at £18,000, a sum that looked relatively strong considering another unascribed cricketing scene from the late 18th or early 19th century made £14,000 at an Andrew Smith & Son in December 2018 (see ATG No 2377).

At the latter sale the location of the match was indeed known: White Conduit Fields in Islington which was an early venue for the game.

Sartorius at the double

Elsewhere at L&T, a sporting picture by equine specialist Francis Sartorius (1734-1804) and two by his son John Nost Sartorius (1759-1828) each drew demand.

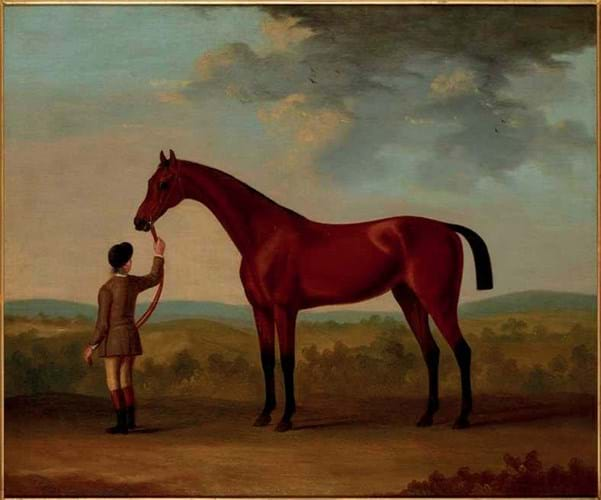

The former was a painting of the racehorse King Herod, a four-mile specialist bred by Prince William, Duke of Cumberland, and made the highest price among the group. The horse was sold to Sir John Moore at the age of seven but, although he won a number of big races at Newmarket and Ascot, his place in racing history today is mostly down to his prodigious breeding career.

King Herod produced numerous offspring – he was apparently still covering mares until his death at the age of 22 – and he was one of three racehorses from which all modern thoroughbreds are descended (along with Matchem and Eclipse). In terms of the art market, any painting of these foundation sires is a valuable proposition, especially by an artist with a strong following such as Francis Sartorius.

The 2ft 1in x 2ft 6in (64 x 76cm) signed oil on canvas here showed King Herod with a groom. Sartorius appears to have painted him a number of times and a mezzotint after one of his portraits, slightly different to the current pictures, was published in 1768.

Consigned from a private Scottish collection, it was pitched at £3000- 5000 and sold at £12,000 – a solid sum for a work by the artist without a mounted jockey.

The two works by John Nost Sartorius meanwhile both came with provenance to The Earl of Kintore and were formerly kept at Keith Hall in Aberdeenshire. First up was a fairly generic painting of a hunter jumping a fence that was signed and dated 1816. Estimated at £800-1200, it took £2200.

Celebrity canine

The following lot was a portrait of a renowned foxhound called Jasper bred by Lord Egremont, shown together with Tom Seabright, a huntsman of the New Forest Hounds. A similar work by Ben Marshall (1768-1834) can be found in The Museum of Hounds & Hunting in Virginia which was made into an engraving in c.1800 and appeared in The Sporting Magazine shortly afterwards.

The commentary that accompanied the engraving stated that Jasper’s hunting prowess meant that ‘he began to acquire the laurel of celebrity’. It added: ‘The whole of the present pack are his own progeny, and esteemed, by the best and most impartial judges, to have as good legs and feet – the finest of all considerations in breeding – the finest symmetry, and the strongest muscular powers of any fox-hounds in the universe…’

L&T described the 13¼ x 16½in (34 x 42cm) signed oil on canvas as in ‘country house condition’ and gave it a £800-1200 estimate. After a good competition it was knocked down at £6000. The extra interest here again showed the difference of having a notable subject.