While the current macroeconomic indicators are far from promising, there is little in the market – at least at this stage – to suggest clock collecting will be buffeted by winds of external strife.

It is worth remembering that inflation has rarely been bad news for the antiques trade (it can pay to put money into assets when index prices are rising) and antique clocks and watches in particular are free from Capital Gains Tax. In the eyes of HMRC, all mechanical objects, regardless of age, are considered wasting assets.

Above all, the passion for clock collecting has proved remarkably resilient whatever has been thrown at it in recent years. Subject to changes in taste, a pandemic and the loss of several key collectors, the market keeps ticking over.

Money on the table

The traditional collector’s favourite, table, bracket and mantel clocks continue to strike the right note. Size is important – they sit somewhat between larger longcase clocks and the smaller carriage clocks – and they can pack a lot of horological features enjoyed by collectors.

Importantly they also encompass clocks made in the English ‘Golden Age’ – the innovative period from the late 17th century to the early 18th century that is so beloved by collectors. The maker’s name, the level of horological complication, case details, provenance, originality, and rarity are all key to pricing.

Dreweatts (25% buyer’s premium) offered two rare table clocks that did well at its biannual curated Fine Clocks, Barometers and Scientific Instruments sale held in Newbury on September 6.

One-off commission

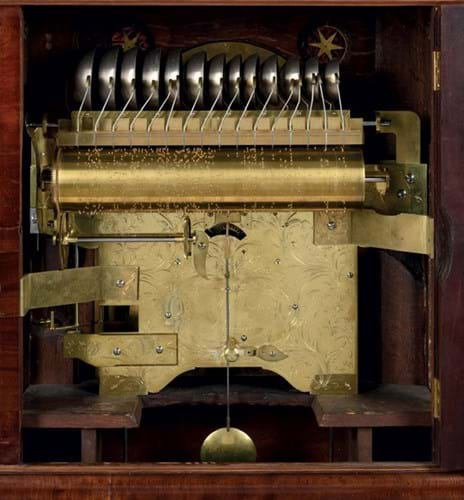

One of these clocks was a rare George III gilt mounted mahogany musical table clock of large proportions by London maker Eardley Norton (1728-92).

Dreweatts noted that the size and quality of the clock would suggest that it was a one-off commission c.1780. Powered by a triple chain fusee movement, it played a choice of 12 tunes via a 14in (35cm) pinned cylinder and 13 bells, while sounding the hour on another larger bell.

With an estimate of £10,000-15,000, it brought £24,000 with the winning bid coming online. Specialist Leighton Gillibrand said it ”really needed to be seen to fully appreciate the presence that it commanded; it really was a lot of clock for the money”.

Rivals collaborate

Also offered by Dreweatts was a fine ebony quarter-repeating table clock c.1685-90. It was signed for Henry Merriman but probably made in the workshop of more renowned maker Joseph Knibb – evidence that, although London’s clockmakers were ‘rivals’ they were never above sharing parts, cases and movements when there was a sale to be made.

Ebony quarter-repeating table clock of Knibb ‘Phase III’ type (detail shown) – £20,000 at Dreweatts.

While the clock case, typical of a Phase III Knibb, had been altered, Gillibrand said: "This lot was just a really nice discovery. Although the visual impact of the alterations to the case are fairly dramatic, they are actually relatively minor and can easily be reversed without affecting the overall integrity of the clock.”

The clock had an estimate of £6000-8000 and sold at £20,000.