During his teenage years he was a keen archaeologist, long before metal detecting became popular. He had uncanny abilities to understand the hidden past, and once discovered an entire abandoned flint-knapping site in a ploughed field at Peacehaven in Sussex.

As a teenager he worked at several jobs and saved money to pursue his passion to go to motor race meetings, of which he was an avid fan. He was also a keen motorcyclist.

In Chelmsford he trained as a librarian, which stood him in good stead. He was an astute editor and proofreader. However, the academic life became tedious for him. He moved to Brighton, to the polytechnic, an active and arts-minded campus.

In Christopher’s spare time he and a friend set up a mobile discotheque - The Music Machine - which was very successful.

During his time in Brighton he also volunteered for the Samaritans.

Car ‘like a wedge of cheese’

His librarian’s training resulted in him joining the V&A, where he worked for two years in the National Art Library.

Not a conventional soul, he insisted on working hours of his own, choosing to arrive later and leave later. He also pioneered the wearing of jeans in the museum, unacceptable until then.

Christopher was famous - or infamous - for driving a bright orange Bond Bug, a three-wheeler shaped like a wedge of cheese, which he was permitted to park within the V&A precincts.

He was on-site, fortunately, when there was a tremendous rainstorm, resulting in flooding of the library, and his alacrity helped to rescue many books and minimise damage.

He found time to set up a business, At the Sign of the Sad Iron, in partnership with Felicity Guille, specialising in domestic metalware. Spit-engines, downhearth goods, candlesticks and lighting were all of interest to him.

In 1974 he was poached from the V&A to become manager of the New Art Centre in Sloane Street. The prospect of life in the Civil Service dimmed in comparison with the challenges of running an enterprising venture promoting new artists. During this time he met, among many others, the artist Prunella Clough, and they became lifetime friends.

Dealing in flat irons was an interest which became very active after he had met his first wife, Rita Adam, and they moved to the Tay Valley in Perthshire. Here they bought a derelict pair of thatched stone cottages and set about renovation. Rita says that he took to this like a duck to water.

For the first bitter Scottish winter they lived in the tin-roofed bothy, sleeping with their dogs for warmth.

Growing market

Christopher still had to continue to earn his living as a dealer. He found that he could buy the relatively unknown Scottish box irons (previously often considered to be Russian), and sell them to a growing market of international collectors.

The demands of building the house and dealing in antiques meant that he would spend weeks in Scotland, then drive the 500 miles south, calling on his network of dealers on the way, and spend time in London. He loved Scotland.

Christopher was innovative and designed his stands at antiques fairs with an artist’s eye. He was one of the first to have a mobile phone - a car-phone was the only option at that time, in 1989, and eye-wateringly expensive - and he was one of the first to subject his antiques to scientific analysis. For both decisions he was mocked by many in the trade, but was proved to be ahead of the game, as no dealer now can be without a mobile and most antiques of value are subject to rigorous scientific analysis.

In 1985 the American Bud Lear was passing through London, and by chance called in at the Chelsea Antiques Fair in the King’s Road. Here he met Christopher, who was exhibiting there, and a long-term friendship was established which resulted in the Lear Collection, and 10 years later the accompanying book.

In addition to showing at the London fairs in the 1980s and early 90s, Christopher also vetted the BADA and Olympia fairs and the now defunct Grosvenor House Fair.

With the opening of his private gallery, The Triangle, in Fulham in 1996, he dropped public exhibitions and received his clients in the dramatic, spot-lit, black-painted and air-conditioned private showrooms.

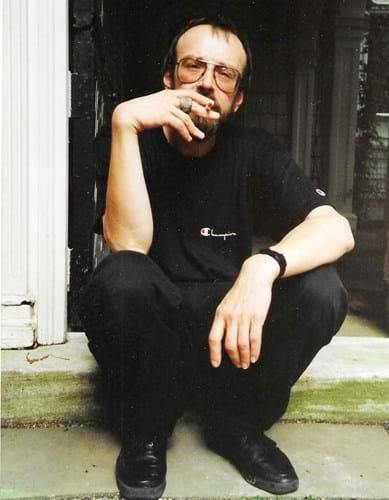

In May this year Christopher died, unexpectedly, of COPD. He was 71.

We were together for 34 years. It always amused me to say: “We went out to dinner twice and have been living together ever since.” We married in 2005.

I have been profoundly touched by comments made by his friends, many of whom say that there is now no-one else like him who they can ring up and chat to about life and the universe. Many have said how kind he had been to them, and many have said how much they will miss his laugh. And one of them said to me: “He was a one-off.” Indeed, he was.

Judy Wentworth