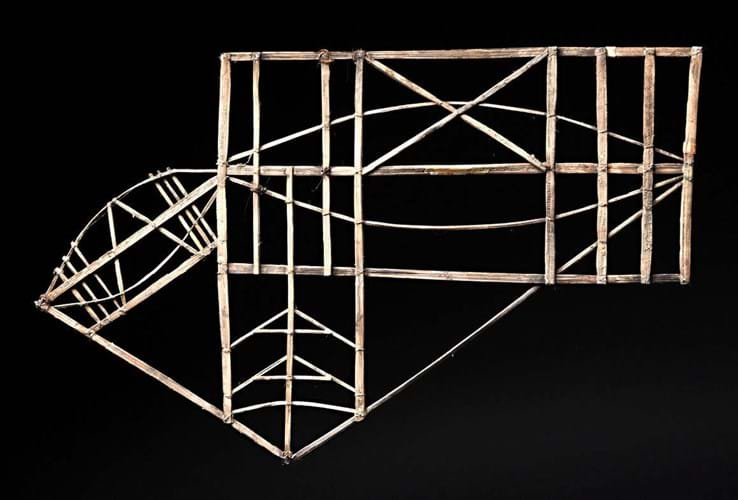

Fashioned from strips of palmwood bound with coconut sennit, they provided vital information about the trade winds and ocean swells around the archipelago of some 1156 islands.

While they had probably been used by islanders for centuries (there is a story that Captain Cook used one in the central Pacific), the existence of these curious charts only became widely known in the West in 1862 when they were described by a Catholic missionary.

They were later discussed in more detail by an Imperial Navy captain stationed in Micronesia in the 1898, by which time the territory had moved from Spanish to German control.

Ocean phenomena

The Marshallese were keen students of ocean phenomena – and protective of what was hugely valuable knowledge. Like a London cabbie schooled in ‘the knowledge’, an experienced pilot or ri-metos would be familiar with the four major swells of the Pacific Ocean – the rilib, kaelib, bungdockerik and bundockeing – and could use them to great advantage when canoeing from island to island. These charts containing hard-won practical information, typically passed down from generation to generation, come in several types.

Meddo charts, tied with cowrie shells at the intersections to represent islands or atolls, depict potential navigation courses. Rebbelib charts featuring chains of islands are similar.

However, mattang were more like training manuals that abstractly illustrate currents, wave and wind patterns. Rather than carried on a boat, the contents were committed to memory prior to a voyage.

These maps – evidence that ancient maps might have looked very different from conventional cartography – continued in use until the Second World War. Most examples that appear for sale were probably made in the first half of the 20th century.

The example offered by Woolley & Wallis in Salisbury at the African, Oceanic & Art of the Americas sale on April 28 had been owned by the vendor for more than 20 years since it was purchased from a family in the US. Fragments of paper labels attached to the lattice suggest it had once been ‘annotated’ at the time of its ‘discovery’.

Specialist Will Hobbs described its dual attraction as both “a piece of abstract art on the wall and an object of wonder”. Estimated at £400-600, it took £11,000 (plus 25% buyer’s premium) from a UK buyer.