Twyssenden Manor, a Tudor house in 258 acres of land near Goudhurst in Kent, spent much of the 20th century as a youth hostel.

However, after the property was acquired in the late 1990s by a City gent yearning for life in the country, it was carefully restored to its former grandeur and then furnished in period style.

The property was recently sold and its contents – oak and vernacular furniture, tapestries, portraits and associated works of art – were offered for sale by Doncaster auction house Wilkinson’s (20% buyer’s premium) on February 27.

Curiously for a collection of this size (the 475 lots generated a hammer total of £678,150) relatively little was known about the earlier provenance of these pieces. However, the owner had clearly been advised by a very capable eye with the emphasis on good colour and patination.

Auctioneer Sid Wilkinson said that across the entire collection, only a very small percentage of pieces were problematic.

The sale recorded some of the highest prices seen in the oak furniture field for some time.

Pictured on the front page of last week’s ATG (No 2533) was an early 17th century English carved and inlaid oak court cupboard or buffet hammered at £88,000. Like most of the top lots in the sale, it went to a UK private buyer.

The name court cupboard comes not from an association with royalty but from the French ‘court’ (meaning short) – a reference to the low height of such a piece designed for storing and displaying plate. Shakespeare mentioned them in Romeo and Juliet as the order is given to clear the hall of the Capulets’ house for dancing: “Away with the joint-stools; remove the court-cupboard; look to the plate.”

‘Just fabulous’

There were several 17th century examples in the collection, most of them of relatively small proportions with carving of the period. One measuring 4ft 2in wide x 4ft high (1.2 x 1.23m), with particularly rich carving and punch work, pilasters carved with flowering plant and bulbous ‘cup and cover’ posts, was described by Wilkinson as “just fabulous”. Pitched at £6000-8000, it took £23,000.

The vendor had been inclined towards the grander style and some of the most fully developed Tudor and Stuart forms. Two coffers were typical. The example from c.1600 was carved with atlantes, caryatids, zoomorphic scrolls and green man face masks and inlaid to three arcades panels with birds perched on flowering plants.

Another from the 1630s had a similarly richly carved facade of arcaded panels with ‘flower-potte’ carving and a frieze rail ornamented with relief-carved male heads, possibly portraits of Charles I.

These were both eagerly contested, selling at £19,000 (estimate £3000- 5000) and £15,200 (estimate £2000- 3000) respectively.

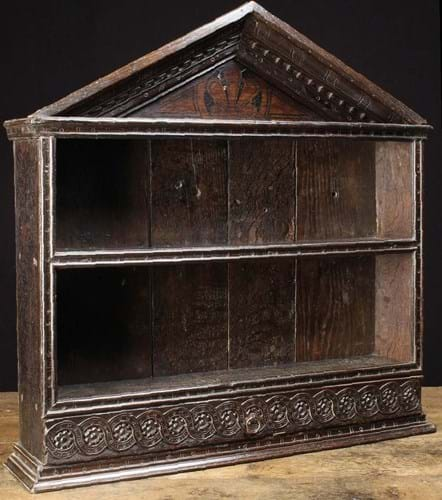

A mid 17th century oak glass case with a triangular pediment, chipcarved and punch-work decoration and a long frieze drawer carved with a guilloche band sold at £9000.

The estimate was just £600-800 but these are rarities. In his Oak Furniture: The British Tradition (1993), Victor Chinnery illustrates several similar boarded glass cases, noting that “cheap and coarsely-made drinking glasses were fairly plentiful even in middle class homes in the 16th century and 17th centuries but owing to their fragile nature some special system of storing them was a necessity. The answer was a lightlybuilt case of shelves, known as a glass case, glass perch or glass cupboard which first made an appearance toward the end of the 16th century.”

Most 17th century versions were made without doors and have open shelves.

Slender proportions

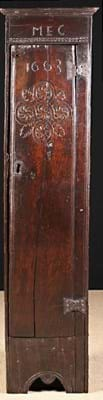

One piece that was easily recognised from a recent sale was a 17th century boarded oak livery cupboard of unusual slender proportions and arched ‘cut out’ feet. The carved decoration includes a quatrefoilroundel and a frieze with the initials MEG and the date 1663.

This piece (the date may be a later addition to a piece that could have been made earlier in the century) was among those sold by Bonhams Oxford in 2014 as part of the Danny Robinson collection. Sold then at £6500, it made £4500 (estimate £4000-6000) this time around.

The late 16th century dining table at Twyssenden was in walnut rather than oak. The base with its fluted baluster legs with carved scroll capitals and vertically gadrooned frieze supported a cleated plank top, measuring 8ft 2in long x 3ft wide (2.2m x 90cm), that could extend to almost twice the length with the addition of leaves drawn out on lopers. It did not quite make its estimate of £60,000-80,000 but got away at £55,000.

A series of boxes, coffrets and caskets from the period – mainly from continental Europe – were well received.

Sold at a top-estimate £6000 was a 13in (33cm) casket carved with armorial crests to the cover and to the front with a panel depicting the Biblical tale of the apostles Paul and Silas accused before the magistrates. The upper and lower friezes carry an inscription in Dutch which loosely translates as ‘be here with us and teach us’. Retaining much of the original polychrome and gilding, it was thought to have been made in Aachen in the 16th century.

A 15in (3cm) late 16th century pine box painted to the lid with a lady and gentleman in Tudor attire and fitted with a heart-shaped escutcheon, lock and key sold at £4400.

Although catalogued as Elizabethan, these ‘marriage’ boxes, and more sophisticated table cabinets, were exported from southern Germany and Switzerland c.1580-1600. Typically painted in polychrome against a metallic bismuth ground, the technique is known as wismut-malerie.

Complex carving

So-called Minnekästchen with complex carved decoration and decorative iron mounts were produced in the Upper Rhine in the 14th and 15th centuries, some probably as betrothal caskets, others as commemorative boxes. A good example was sold at Christie’s in 2021 as part of Syd Levethan’s Longridge collection for £13,000. The casket here, measuring 6½in (16cm) wide with all-over floral decoration brought £4700 (estimate £4500-5000).

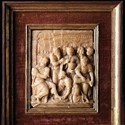

The town of Mechelen in the province of Antwerp was a major centre of alabaster sculpture from the mid-16th century onwards. The craftsmen there even had a dedicated name: they are described in guild records as cleynstekers (meaning sculptors of small-scale works) and albastsnijders (alabaster cutters).

The narrative panel, typically depicting scenes from New Testament and the Passion cycle, was the mainstay of the Mechelen cleynstekers. There was something of a production line for these, particularly after the Southern Provinces were reconquered by Catholic Spain in 1585.

Examples come to sale quite frequently in continental Europe but less often in the UK. There were several among the contents of Twyssenden Manor, including a pair c.1700 carved with The Way to Calvary (Saint Veronica offering her veil to Christ) and The Garden of Gethsemane. Both enriched with gilt detailing, they were set in original gilt and strap-work frames measuring 9 x 8in (23 x 20cm).

Estimated at £2000-3000 (not an unduly modest estimate), they went to a UK private collector at a punchy £15,400.

The names of most alabaster cleynstekers are unknown. However, one carver who regularly signed his work was Tobias van Tissenaken (1560-1624). Records suggest he was active from 1596 until his death and was elected dean of the Guild of Saint-Luke of Mechelen in 1619.

An early 17th century plaque depicting Christ washing the feet of his disciples, signed with his monogram to the lower ledge and set in a crimson velvet clad frame with moulded gilt borders, took £6100.

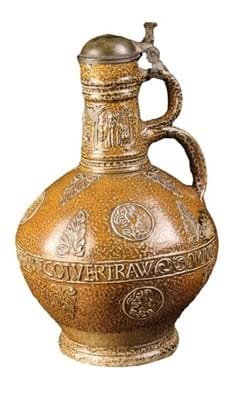

Sold at a low-estimate £5500 was a 16th century Frechen stoneware flagon with double loop handle and original domed pewter lid. Standing 10in (25cm) high, it was applied with portrait medallions, images of Christ Pantocrator and a band of repeated text reading Ominsoe Ingol Vertraw.