Frank Milner at the exhibition of some of his collection running at Lady Lever Art Gallery.

Image copyright: National Museums Liverpool, courtesy of Frank Milner

Retired art historian Frank Milner, 73, whose work specialised in British and European paintings, is a collector of Japanese woodblock prints.

Sixty-eight works by the 19th-century designer Toyohara Kunichika from his collection form the Kunichika: Japanese Prints exhibition at Lady Lever Art Gallery in Port Sunlight, Wirral, until September 4. Kunichika (1835-1900) was best known for depictions of Kabuki theatre.

ATG: How did you get the collecting bug?

Frank Milner: There was an exhibition held at the V&A in 1973 called The Floating World, which was an overview of Japanese prints from the 18th and 19th centuries. I was completely knocked out by it.

I bought my first Japanese print – of an actor playing a sumo wrestler – really cheaply in a junk shop in Penny Lane in Liverpool when I’d gone to the off-licence to buy a bottle of wine. I think I paid about five quid for it, which was probably a bit too much actually because it was part of a triptych rather than a self-contained print. But the design of a wonderful, big blue fish curling around the fabric of his clothes, I thought was great.

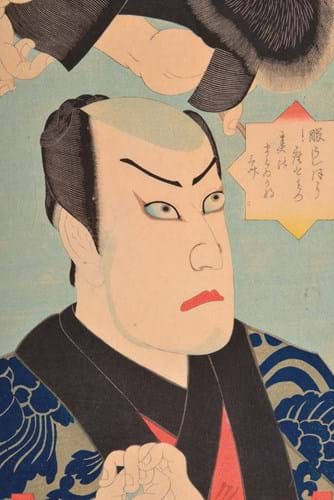

Actor Ichikawa Danjuro IX as Kamakura Gongoro Kagemasi in the ‘Wait a minute!’ (Shibaraku!) scene, 1895. One of the most famous kabuki scenes where the hero in his giant persimmon sleeves, decorated with the huge three-rice measures personal crest of the actor, interrupts the action. A scene beloved of kabuki fans, usually accompanied by applause, cheering and shouts.

Image copyright: National Museums Liverpool, courtesy of Frank Milner

What drew you to Japanese prints?

They’re very strong and powerful images. In the West, the image that jumps to everybody’s mind when they think of Japanese prints is a big blue wave by Hokusai, or prints by Hiroshige that were copied by Van Gogh or were collected by Monet and influenced his garden design. But I was quite excited by the bold and emphatic, impactful designs of Kabuki theatre prints.

What elements do you look for when considering a purchase?

I’m interested in condition, but I’m not that interested that I necessarily want a print to be perfect. I accept that there’s a trade-off between condition and price, obviously, but the condition of the colour is important. The subject matter as well.

There’s not really been a focus on the Kabuki plays that the prints are illustrating and, in certain Kabuki plays, there are really interesting social things going on. For example, plays about women gaining greater freedom, like riding unaccompanied in rickshaws.

At one level, my collection is a personal take on Kunichika; at another level, it’s trying to show the variety of work that he did over a 40-year period; at another, it’s taking Kunichika as a conduit for images that are reflective of changes in Japanese society – and there was a lot going on between 1870 and 1900.

Actor Danjuro IX having a wig lowered onto his head seated and reflected in his dressing room mirror. From the print series Mirror of true likenesses of actors backstage, 1868.

Image copyright: National Museums Liverpool, courtesy of Frank Milner

What social changes are reflected in Kunichika’s work?

The big one is the availability of photography in Japan from the 1860s onwards. Of course, photography threatens – as does machine printing – hand-printed art forms because they can do it quickly and cheaply.

I argue in the exhibition that publishers and print designers tried to push back using their strengths. Number one was full colour. Number two was price: two bowls of buckwheat noodles for a single sheet print, as opposed to say seven or eight bowls for a carte de visite sepia photograph.

The more interesting thing was the actual visual strategies for holding on to the market that were employed. There’s a little section in the exhibition, called Intimacy, where there are close-up views of actors in their dressing rooms, having their wig put on or their sweaty faces fanned by an assistant. This gave a directness.

And for the person who was buying the print, the fan of the actor, it gave them something that you couldn’t do with a little photograph because, to get the photographs taken, you had to stand very still.

The titles of the prints themselves are interesting, like the short series called ‘Modern People in Photographic Style’. It’s quite clear that, in that particular case, there’s a very conscious awareness of the competition.

Going big was a solution. There always had been triptych prints, where they made a big picture out of three bits of paper, but to have one figure at half-length was a much more powerful, punchy image.

That was something that Kunichika led with. Kunichika’s best work is thought of by quite a lot of people as being those straightforward, half-length triptychs in close-up, a CinemaScope in a way.

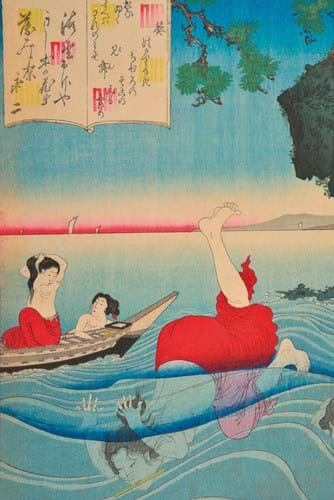

Abalone Divers at Aoi (Chapter 34). From the Bijin-e series Fifty-four feelings matched with chapters of the Genji, 1884. The composition and subject matter of this image derives from an earlier print by Kunichika’s master Kunisada.

Image copyright: National Museums Liverpool, courtesy of Frank Milner

Where do you find prints to buy?

All over the place. There are two people that I think are good in this country: Toshidama Gallery in Somerset, an online business; and Japanese Gallery Kensington in London. The galleries in Japan are the ones I look to first, though.

Sometimes you get things that turn up on eBay, although I’m deeply wary. I prefer to deal with creditable dealers rather than with individuals.

What’s the most you’ve spent on an item for your collection?

The most I spent was on the three-sheet print of the play Shibaraku Kunichika did in 1895 that we used for the exhibition poster. I spent £2500 on that one print. But a much more typical cost would be £200- £300 for a triptych. I classify it as an affordable vice.

How large is your collection?

I’ve no idea, maybe 250 or 300 prints. I’ve got about 120 by Kunichika and quite a lot by other artists as well. The other artists that I can collect and that are affordable are Kunisada, who was Kunichika’s master in a sense, and I’m very fond of Kuniyoshi. I’ve only got one Hokusai because he’s expensive. If I won the lottery, I’d buy some more.

Geisha Some of Yanagibashi holding a cat, from Tokyo sanjuroku kaiseki (from the series Thirty-six restaurants of Tokyo), Toyohara Kunichika, c.1870.

Image copyright: National Museums Liverpool, courtesy of Frank Milner

How do you display your prints at home?

Floor to ceiling, and on the staircase and hallways they’re nine or 10 deep. On the backs of doors, too. We’re running out of space. The trouble is having to keep the curtains drawn, because you’ve got to be careful not to get bright sunlight onto the colours as they’re fugitive. It’s becoming a bit of a problem, I must admit.

They’re beginning to be stacked up on the floor and I’ve got to the stage where I get people to adopt them. I’m not giving them to them, but I foster them out. I look at other people’s stairwells and think, ‘You need a few of my prints there for the moment’. Some of them have been in other people’s houses for a few years now and I’m getting a bit worried that they might think they own them. I’ve even got a relationship with one particular couple where I change their prints every 18 months. They get a circulating collection.

Have you ever considered selling prints from your collection?

No, I haven’t. I don’t know what I’m going to do with them when I die. That might not be my problem to sort out.

Is there one print you’re still looking for?

No, it’s not like that. I’m not looking for the philosopher’s stone. If I had more money to spend I’d like some of the large head prints of actors that Kunichika designed that are expensive. But the thing about Kunichika is that you can put together a collection of his works and not have a load of dosh.

How has the market changed during your time collecting?

The market in Japanese print collecting has expanded as more people know about Japanese prints.

The internet has made an enormous difference, in terms of the accessibility of catalogues online so that people can see what’s out there.

The second thing, which is hugely important, is this worldwide collective website ukiyo-e.org. There’s been an agreement to amalgamate the online image websites of the most important collections in the world in museums including in Boston and in Japan, the British Museum and also a number of dealers. There are hundreds of thousands of images. This, as research, has been enormously important.

What advice would you give a young collector?

Don’t buy anything until you’ve found out how it all works. You can very easily spend a few hundred pounds on something that’s not that good. Take your time and follow your own tastes, and never do it for investment.