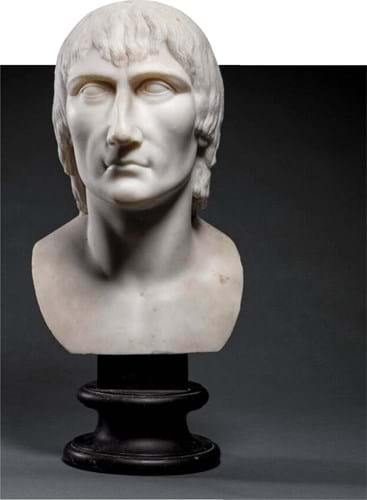

Rediscovered in 2020, this 1797 portrait bust by Giuseppe Franchi is the earliest known sculpted likeness of Napoleon Bonaparte. It took £140,000 at Sotheby’s.

Sotheby’s (25/20/13.9% buyer’s premium) sale of Master Sculpture from Four Millennia staged on July 5 included an important rediscovery: the earliest extant sculpted portrait of Napoleon Bonaparte. Estimated at £120,000-180,000, it took £140,000.

Carved in 1797 by the Carrara-born sculptor Giuseppe Franchi (1731-1806), the 16in (41cm) bust depicts the victorious commander-in-chief of the French Army of Italy following the fall of the Venetian Republic on May 12, 1797.

It is concurrent with Napoleon’s first major campaign of visual promotion which included commissions for painted portraits from Antoine- Jean Gros (1771-1817), Andrea Appiani (1764-1817) and Giuseppe Longhi (1766-1831).

The sitter wears the oreilles de chien (dog ears) hairstyle which was fashionable in Directoire Paris and assumes a pose recalling portraiture from the last days of the Roman Republic.

Although signed and dated Jos: Franchi facieb: Mediol: 1797, the marble was purchased in Paris as recently as 2020 when the subject was unidentified. Research by Prof Olivier Ihl, emeritus professor at the Sciences Po Institute of Grenoble, rebuilt its history from surviving correspondence.

This bust is almost certainly related to a dinner held by Napoleon just days after victory over Venice at Palazzo Serbelloni in Milan to which Franchi, then professor of sculpture at the Accademia di Brera, was summoned.

Napoleon saw the finished bust when he visited Geneva on November 22, 1797 – an encounter described in a document from January 1798: ‘We came to the room which contains various objects of curiosity which attract the attention of enthusiasts; there the General found his bust. He was asked if he recognised himself; he replied that there was some resemblance, but that it was embellished.’

However, by 1815 and Napoleon’s final defeat, Franchi’s bust was valued for sale at a mere Fr1200. The city of Geneva and the King of Sardinia both declined to purchase it and it was finally sold ‘to an Englishman’ on August 31, 1818, for ‘80 gold Louis’.

Sotheby’s European sculpture and works of art specialist Christopher Mason said: “The rediscovery of this bust tells the story of a famous sculpture, created as a triumphal symbol of Napoleon’s power. Initially much appreciated, it was rejected after the fall of the empire, deemed worthless and ultimately lost without a trace for two centuries.”

He also added a small corporate connection to the story: “The fact that it was commissioned for the first time in a building that now houses Sotheby’s Milan, and that Sotheby’s has rediscovered it, closes the circle of history.”

It is quite possible an even earlier bust of Napoleon is out there somewhere. It is known he commissioned a likeness from Giuseppe Ceracchi (1751-1801) in October 1796, although it is today known only from copies.

Remarkable manuscript

This rediscovery of the 1797 bust headlined a number of important lots relating to France’s most famous military and political leader offered across the UK in July.

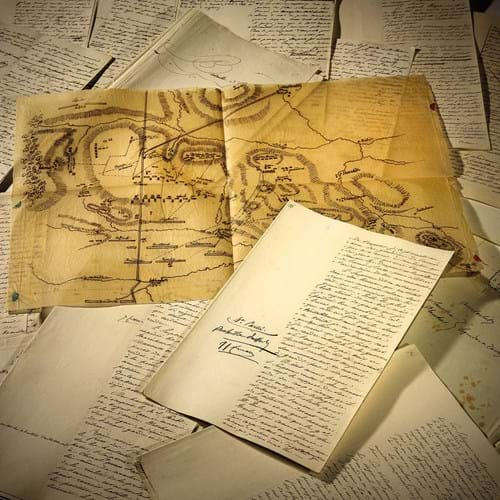

Christie’s (26/20/14.5% buyer’s premium) mixed-discipline Exceptional sale on July 7 included a remarkable manuscript that amounted to Napoleon’s personal account of victory at the battle of Austerlitz (December 2, 1805).

The legend of Austerlitz as Napoleon’s tactical masterpiece continues to grow. “The battle”, wrote Frank McLynn in his 1997 biography, Napoleon, “was to him what Gaugemela had been to Alexander, Cannae to Hannibal and Alesia to Julius Caesar. For the loss of 1305 French dead and 6940 wounded he had inflicted 11,000 Russian casualties and 4000 Austrian, captured 40 colours and taken 180 cannon.”

On hearing the result, William Pitt the Younger is said to have commented: “Roll up that map of Europe. It will not be needed these 10 years.” The Holy Roman Empire was dissolved the following year.

An annotated copy of Napoleon’s personal account of victory at the Battle of Austerlitz – £220,000 at Christie’s.

Dictated to General Henri-Gatien Bertrand (1773-1844), latterly Napoleon’s grand maréchal du palais and one of his aides-de-camp at Austerlitz, the 77 leaves of different paper stock include extensive cancellations, amends and additions in a number of hands including approximately 120 words inserted by Napoleon himself. It was part of a cache of archival material that remained in the Bertrand family until its dispersal at a series of auctions at Drouot, Paris, in the 1970s-80s (this one acquired by the family of the vendor c.1975).

Although described in Christie’s catalogue as ‘Napoleon’s definitive version, written in the early years of his final exile in Saint Helena’, eleventh hour information indicated that the manuscript had been composed within three years of the battle itself. It is now thought to be a draft for the text delivered to the Imprimerie impériale in March 1810, but not published.

One passage recalls the emperor’s tour of his army in the evening before battle, during which troops spontaneously created a firelit procession for him with torches made from straw. Napoleon recalled his response at the time: “This is the most beautiful evening of my life; but I regret to think that I shall lose a good number of these fine men.”

Later the narrative relates the moment a despairing young Russian officer threw himself at Napoleon’s feet crying “I am unworthy to live … I have lost my guns”, to which Napoleon responded: “I approve of your tears, but one may be beaten by my army and still have a claim to glory.”

The main narrative was to have been accompanied by a series of maps, tables and engravings showing the composition of the respective armies and their manoeuvres before and during the battle. Only the single map of the battlefield survives with the manuscript: this is on tracing paper, in ink over an initial pencil draft, probably in the hand of Bertrand.

It was expected to bring £250,000-350,000 but fell a little short, selling to a single bid of £220,000.

Presentation pistols

A pair of Napoleonic presentation flintlock pistols by Nicolas-Noël Boutet – £780,000 at Christie’s.

The following lot in the sale was more eagerly contested: a pair of presentation flintlock pistols made by the Versailles gunsmith Nicolas-Noël Boutet (1761-1833). Richly embellished with the Graeco-Roman and Egyptian ornament that epitomise the period, they carry the serial number 345 for 1809.

Their presence in the Palace of Tzarskoe Selo, St Petersburg, in the 19th century led to speculation that they had been captured from the French baggage train during the retreat from Moscow in 1812. It is more probable that they were presented by Napoleon to one of the eight Russian recipients of the Grand Aigle of the Légion d’Honneur.

They were later owned by William Goodwin Renwick (1886-1971) who amassed one of the great collections of antique firearms in the decades before the Second World War, and they were last sold at Sotheby’s in July 1972. Estimated at £300,000- 500,000, they took £780,000 at Christie’s.

Boutet was named Directeur Artiste of the newly formed Versailles Arms Manufactory in 1792 and in 1795 was appointed head of the newly created Arms de luxe department, responsible for richly decorated presentation arms suitable for military heroes or heads of state.

Victory prize

A six-piece presentation garniture of Boutet weapons comprising a gold inlaid rifled carbine, carriage pistols, pocket pistols, and a dress sword and scabbard sold for $2.5m (£1.875m) or $2.875m when buyer’s premium is included at Rock Island Auction Company of Illinois in December last year (ATG No 2522).

Made at the Versailles Manufactory in 1797 at the moment when Napoleon was rising to power, it was purchased by the Directory of the French Republic for 1000 guineas and presented to General Bonaparte following ‘his victories over the Austrians and Sardinians’. The garniture previously sold at Christie’s King Street in 1991 for £105,000.