While a few pieces with Stonehaven and Ellon marks are known, Keith silver, made in the Moray town with a population numbering less than 5000, has rarely appeared at auction – the last example spoon offered in the 1990s.

A humble 19th century fiddle pattern teaspoon came for sale at Lyon & Turnbull’s (25% buyer’s premium) Scottish Works of Art sale in Edinburgh on August 18.

As with the two examples illustrated in Jackson’s Silver & Gold Marks of England Scotland and Ireland, it was marked JC, probably for John Cumming, a watch and clockmaker in Keith. The town name is built from five oddly shaped letter punches, perhaps made by Cumming himself. The estimate was £1000-1500 but it did even better, selling at £2200.

Spoons by Alexander Glenny who worked in Stonehaven, c.1840, have made even more. One took £3400 at L&T in 2008.

Silver made a major contribution to the day’s £308,000 hammer total, led by the Charles I Steeple Kirk communion cup. The 9in (23cm) tall cup was from a communion set commissioned c.1640 for the historic kirk by a city merchant from Robert Gardyne II, one of a dynasty of Perth and Dundee smiths. One of the three known surviving cups is in Dundee’s MacManus Museum and L&T sold another to a collector in 2013 at £17,000 to raise restoration funds for the 12th century kirk.

Sold for the same reason, this third example, pitched at £20,000-30,000, sold on the lower figure to a buyer using thesaleroom.com.

Ballater is another rare provincial name but near enough Balmoral for local jeweller and silversmith William Robb to be given small commissions by Queen Victoria and Edward VII. He also made uniform items for Victoria’s own staff, the Balmoral Highlanders, and sold numerous smallwork pieces to visitors on the tourist trail.

A four-piece bachelor’s tea and coffee service is a rarer piece by Robb. The example here marked WR, BLTR. Robb Ballater and bearing assay marks for Edinburgh 1911 and 1912 doubled expectations at £1500.

A recently discovered spirit kettle and stand, c.1776-79, marked for James Gordon of Aberdeen, was only the third Scottish example known to have been made outside Edinburgh. The 14in (35cm) tall, once-fashionable tea accessory went above estimate at £8500.

Scottish provincial coffee pots are also uncommon. The example at L&T, marked CA, ABD – for entrepreneur Coline Allan, silversmith, watchmaker and founder of a factory making granite table tops and chimneys – was one of only three known to have been made in Aberdeen.

The heavily embossed pot doubled the mid-estimate selling at £9000.

Thirteen of the Jacobite lots on offer came from Tornaveen House, Aberdeenshire, owned by a Fraser family directly descended from a line of Lovat Frasers and Farquharsons – famous Jacobite clans – living there since 1670.

Of considerable interest to historians were letters by and to Lord Lovat and some by friends describing his execution in 1747, a year after he fought for the Stuart cause at Culloden. “Poor Lord Lovat was beheaded a few hours after writing my last”, wrote one. “He behaved like ane old true Duilnach quite undaunted even to the last, Made Several witty Speeches which seem’d quite agreeable to the Bulk of the People…”

Estimated at £600-800, the letters made £2800. Like the great majority of lots in the August 18 sale at Edinburgh, and all those mentioned in this report, the buyer was a private collector.

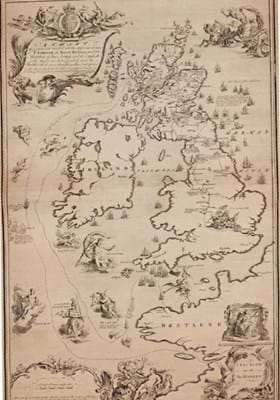

Also pitched at £600-800 was a rare map by Colonel James Alexander Grante, detailing all the routes, sieges and battles of Prince Charles’s and the Government armies during the campaign. Published in 1747, the 25 x 16in (64 x 41cm) map, a reduced version of one in the Royal Collection, sold at £4000.

Probably the most popular of all Jacobite material are contemporaneous wine glasses engraved with symbols of loyalty to the Stuart dynasty. So popular, indeed, that within 70 years of Culloden they were being faked – sometimes no more than later engravings on 18th century glass – to meet the ever-growing market.

No such problems with the best of the glasses at L&T: a pair similar to those once at Chastleton Manor, Oxfordshire, home of the Cavalier Society, and now dispersed among collectors and the National Trust.

On domed feet and air-twist stems, the trumpet bowls appear to have been decorated by the same engraver with the symbolic open rose and rosebuds and the word Fiat above an oak leaf. A similar single glass took £2400 at L&T in 2018. This pair estimated at £1500-2500 made £3800.

The outstanding jewellery lot was another richly Jacobite Tornaveen House consignment: a silver brooch with citrine set in smaller diamonds and engraved H Farquharson killed at Culloden 16th April 1746. Offered with three small gold memento mori brooches and a seal wax impression and estimated at £500-800, it made £3400.

Great Scott

If there is any link to match the potency of a Jacobite connection in Scotland it is Sir Walter Scott, who did so much to promote the romance of Highland history.

A silver-mounted pistol engraved with the armorial, crest and motto of Scott of Abbotsford and signed McLeod was very similar to a pair Sir Walter commissioned from the rather obscure Scottish gunmaker prior to George IV’s 1822 visit to Scotland which the novelist largely orchestrated.

Like that pair, still on display at Abbotsford, the 13½in (34cm) long flintlock pistol was made in 18th century style and sold at the lower £15,000 estimate.

It wasn’t all easy going for traditional Scottish offerings.

Before aftersales substantially improved the figures, 17 of the 41 Wemyss items failed to get away.

Most went around realistic estimates but an outlier was a 5½in (14cm) mug inscribed New Year 1899 From Some Old Ms Friends At Wemyss. With impressed mark, it tripled expectations at £1200.

Mauchline also had a tough day, only half the 11 lots selling in the room (aftersales reduced casualties to just one). Top-seller was a late 19th century 7½in (19cm) tall ‘Tartanware’ ware box of six volumes of poetry by Sir Walter Scott which sold below estimate at £460.

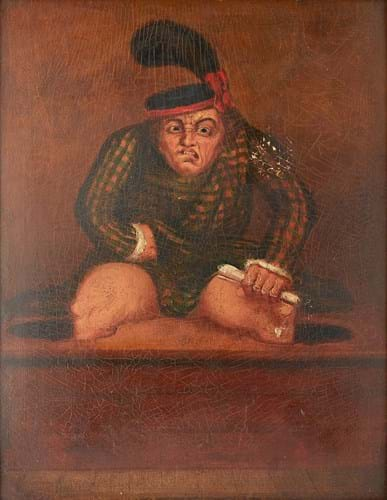

Today this insulting piece of propaganda would unite Scots against the Government which produced it. In the post-Culloden 18th century it was aimed at the bolstering the prejudices of Lowlanders (or Sassenachs as Highlanders called them) and the English. Part of the programme to obliterate Highland culture, the oil-on-panel caricature depicts an uncouth ‘primitive’ Scot unable the use the modern lavatory, with legs suspended down each bowl. Based on a similar image of folklore cannibal Sawney Bean, it doubled Lyon & Turnbull’s top estimate in selling at £1600.