While dozens of vintage wristwatches have passed the seven-figure barrier at auction in recent years, only a handful of antique clocks have ever attracted a £1m price tag. But they do exist.

Back in June 2019 Bonhams sold the miniature Thomas Tompion ‘Q’ clock made for Mary II, c.1693, for £1.6m.

In 2015 dealership Carter Marsh sold the ‘Medici’ grande sonnerie Tompion for around £4m as part of the Tom Scott collection. This year the Winchester firm has offered the first tranche of the John Taylor collection, selling the ‘Mudge Green’, a marine chronometer c.1776-79 by Thomas Mudge priced at £1.2m and entertaining offers of around £3.5m for the ‘Spanish Tompion’, another magnificent clock from the celebrated grande sonnerie series.

Overflowing with Golden Age rarities, the Taylor collection overshadowed much of what was offered at auction in London and further afield this year.

However, its presence (first at the Ronald Phillips gallery on Bruton Street and then in Winchester) also helped add value to what was in the salerooms. In particular, the transparent pricing and accessible cataloguing gave buyers a better-than-usual idea of the relative merits of different types of Golden Age timekeepers.

Details matter. Take the two Tompion ‘quarter repeating’ table clocks offered by Bonhams and Sotheby’s. At first glance they might look alike but on closer inspection they were quite different.

International interest

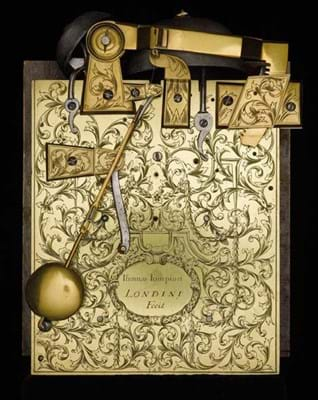

The Tompion in Bonhams’ (27.5/25/20/14.5% buyer’s premium) Fine Clocks sale on June 22 was a 13½in (35cm) quarter repeating table timepiece from c.1680-85.

The first detail of interest is that it predates the numbering system introduced at the Tompion workshop to aid with the accounting process. Secondly, although it has a bell and repeating work set into the backplate, the clock is, strictly speaking, only a timepiece.

James Stratton at Bonhams said: “The clock is not a striker; however, the hours and quarters can be struck at will by pulling a cord from either side of the case.”

One of only a small handful of similar eight-day clocks, all of them with ebony ‘Phase One’ cases, it sold for £125,000 against an estimate of £65,000-90,000. The buyer was a US enthusiast (a Tompion table clock sold by Bonhams in December 2020 for £210,000 also sold to North America).

Stratton added: “As a general trend most top lots now go to private buyers and not the trade. Buyers are also more internationally based.”

He is witnessing more purchases of high-value clocks being made online without a traditional prior viewing – both recent Tompions sold without the buyers seeing the clocks first.

Name recognition

Sotheby’s (13.9/20/25% buyer’s premium) Tompion, the opening lot of the July 6 Treasures sale, was a numbered clock – the digits 168 dating it to c.1690. It is one of a small group of repeating clocks marking the transition between the workshop’s first clocks, made without subsidiary regulation and strike silent dials, and the ‘Phase Two’ clocks with fully developed dials.

The auction house commented that the foliate lower spandrels to the dial are very unusual for Tompion and appear on a very few clocks at around this date. It may also be possible to link the clock with its original owner: it was probably originally purchased by General Charles Churchill of Minterne Magna, Dorset (1656-1714), brother of John, 1st Duke of Marlborough.

Jonathan Hills, from Sotheby’s, emphasised the importance of a name: “It is the crucial thing. Clocks with a major maker’s name get attention.” He said about the piece: “The clock was in country house condition and wasn’t perfect and this was reflected in the value. It had good provenance, however, and was largely in an untouched original state.”

It sold for £80,000 against a more bullish estimate of £80,000-120,000.

Hills observed that other clockmaking periods are now beginning to be appreciated. Sotheby’s enjoyed measured success with a trio of late 18th century gilt brass and paste clocks made for the Chinese market.

The only one to sell in the room was by specialist Clerkenwell maker John Mottram whose clocks were much enjoyed by the emperor Qianlong and are still on view at the Palace Collection, Beijing. Standing 21in (53cm) high, it included both a musical train and an automaton to the top surmount. Seven paste-set rosettes spun around a central pink and white rosette while another rotates along with the red and white finial.

“It’s very rare and lifts the clock up to another level with this extra layer of complication to the automaton,” said Hills.

The clock made £220,000 against a guide of £250,000-350,000.

Much more was expected for a yet more complex Mottram creation of a similar date – a 3ft (92cm) high pagoda clock set with enamelled panels of river landscapes and a silvered dome of spinning glass rods simulating a fountain. The ‘Swan Clock’ by the same maker sold in Sotheby’s Treasures sale in 2014 for £2m and the guide here was £1m-1.5m.

A clock such as this, appealing to collectors in China and internationally, may have suffered a little from the absence of international collectors in London, due to travel restrictions. However, although ‘unsold’ on the day, it is understood to have found a buyer soon afterwards at a price around the low estimate.

Hills added: “The market is still strong for great pieces across the board but it’s got to be the right thing. People are looking for statement pieces and the piece itself needs to be absolutely right. Buyers today are very discerning. Overall, there are not as many pure horological collectors around - some of these collectors have now been priced out of the top end of the market.”

Spectacular orrery clock

A spectacular orrery clock made for the conseiller-secrétaire of Louis XV led Christie’s (14.5/20/25% buyer’s premium) horological offering – limited to just two lots in the firm’s Exceptional sale held on July 8.

Standing an imposing 7ft 10in (2.4m) high in its ormolu-mounted kingwood case, it features quarter-striking, goes for a month and includes both a calendar and equation of time. Described as ‘a tour de force of horological and scientific complexity’, it was originally designed by and made for Jacques-Thomas Castel, Conseiller- Secrétaire of Louis XV c.1763.

The clock’s provenance includes ownership by Baron Mayer Amschel de Rothschild and his descendants at Mentmore Towers and its sale by Sotheby’s in 1977 for a mighty £40,000.

Toby Woolley, Christie’s clock consultant, said: “The clock was a unique piece with great provenance and a well-documented history. It was a centrepiece item when it stood in the Great Hall of Mentmore. In all a spectacular timepiece.”

It had some alterations including the dome under the figure of Father Time which is a later addition. Selling at £380,000, the clock fell just short of the lower estimate.