When in 1900 the art dealer Ambroise Vollard published his first book it caused a sensation.

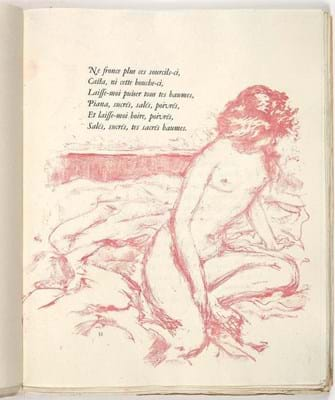

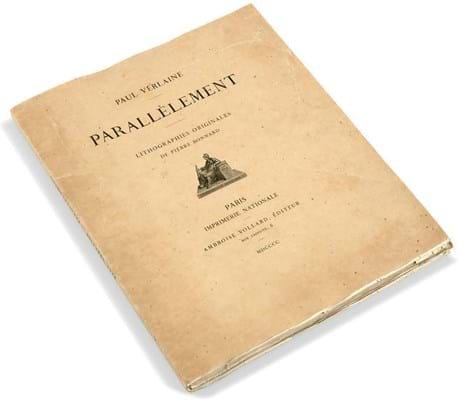

He’d commissioned a young Pierre Bonnard to provide the 109 sanguine chalk illustrations encircling the pages of Paul Verlaine’s Parallèlement, a series of poems that juxtaposed religious life with debauchery. It was not, as an outraged printer quickly discovered, a treatise on geometry.

The 230 copies of Parallèlement were not just considered licentious. Lithography was not deemed an appropriate medium for book illustration and an upstart avant garde artist an unsuitable choice for a professional illustrator. Today Vollard’s experiment is often dubbed the first modern artist’s book – or (the term first used in The Studio magazine in 1960), the livre d’artiste.

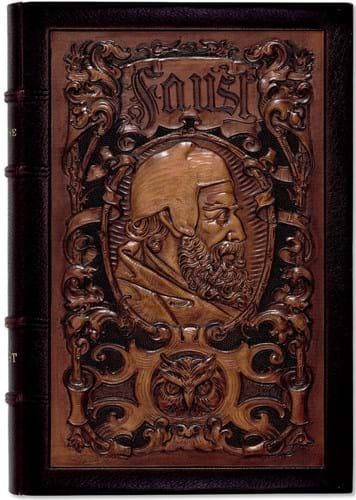

Drawing a start line isn’t easy. Books have contained art, and artists have made books, for generations. In France itself Delacroix had illustrated Faust as early as 1828 while Manet had provided lithographs for a translation of Edgar Allen Poe’s The Raven in 1875. Important too was the work of William Morris at the Kelmscott Press and that of the visionary artist and poet William Blake.

However, in Parallèlement the genre as it developed in the 20th century began.

Championed by an art dealer interested in publishing rather than by a publisher interested in art, it contained original works of art produced for the project, it used traditional printing techniques, it was envisaged as a deluxe product, it was created in a signed and numbered limited edition and the artist was given freedom of creativity to interpret the text.

In this in particular the artist’s book differed from the tradition of professional book illustration when – for example in the work of Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz) in Charles Dickens novels – the job of the engraver was simply to follow the story with visuals of the narrative.

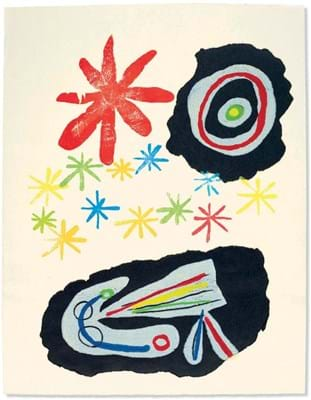

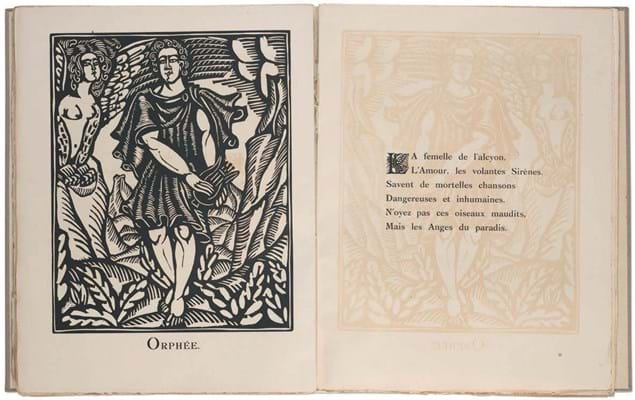

When creating an edition of Éluard’s À toute épreuve, Miró, wrote: “I have made some trials which have allowed me to see what it was to make a book and not merely to illustrate it. Illustration is always a secondary matter. The important thing is that a book must have all the dignity of a sculpture carved in marble.”

The avant garde

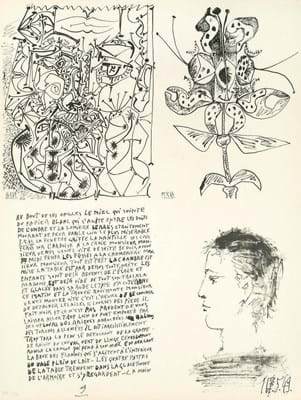

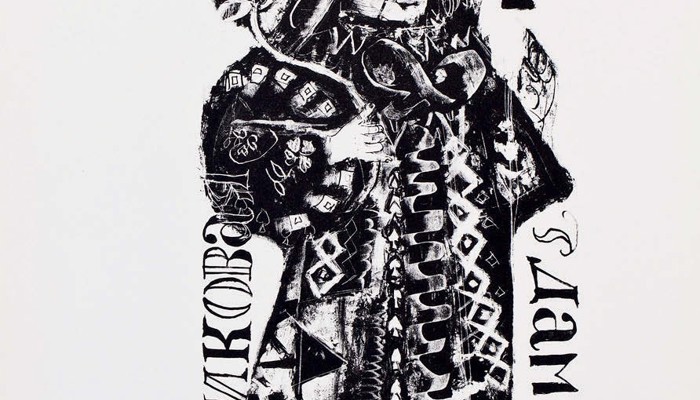

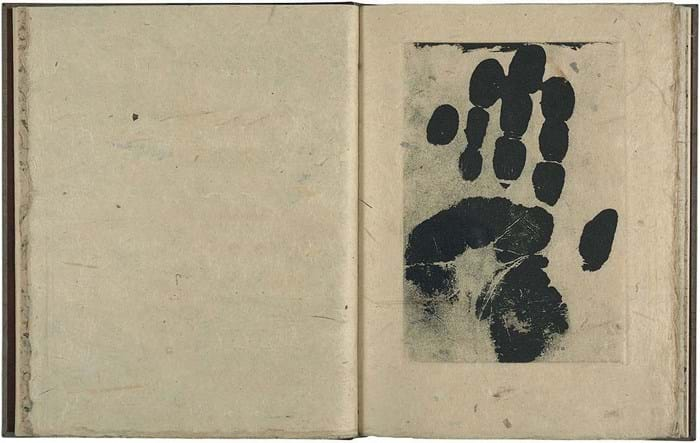

Leading Part I of the Destribats collection sold in July 2019 at Christie’s in Paris was this 1936 firstedition copy of 'La Barre d’appui', a volume of poems by Paul Eluard. This copy is one of small number that include an extra engraving – an aquatint of Picasso’s right hand. The work soared past its high estimate of €150,000 to realise €532,000 (£425,000).

From the beginning, livres d’artistes were tied to the avant garde. As the genre took hold in the creative milieu of early 20th century Paris, texts by the city’s writers and poets were matched with images by its artists and sculptors.

It was shaped too by radicalism and in particular the explosive potential of images and text witnessed in the pamphlets, posters and manifestos that emerged across the continent and in Russia as Europe plunged headlong into war.

As much as any medium, artist books mark key moments in the Modern movement, from the Fauves’ unleashing of colour, the Cubists’ dismantling of form, the Futurists’ celebration of dynamism, Dada’s rejection of logic and reason and the Surrealists turning inward. The mixing of words and pictures were central to Dada and Surrealism in particular.

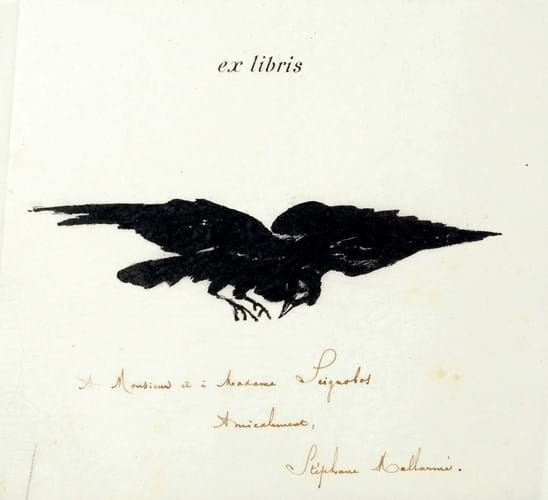

Edgar Allan Poe’s 'Le Corbeau' (The Raven) was translated by Stéphane Mallarmé in 1875 with his close friend Edouard Manet providing half a dozen lithographs for an edition of 240. Both Mallarmé and Manet signed the edition with this presentation copy, sold for £25,000 at Bonhams in March 2020, inscribed for Charles and Dinah Seignobos. They had met the poet when he was a schoolteacher in Tournon in the Ardèche in the 1860s and worked to give him a pay rise and paid leave. 'Le Corbeau' was a commercial failure and the venture, a full 25 years ahead of its time in concept and design, was not repeated by the publisher. Photo: Bonhams

Virtually every major painter and sculptor of the 20th century – Rodin, Braque, Ernst, Matisse, Maillol, Kandinsky, Dalí and Giacometti, to name a few – collaborated in the creation of one or more such works and some, such Picasso, would become prolific in the genre.

From the beginning, livres d’artistes were designed as collectors’ items that might enhance their status.

Prints were frequently offered in two forms: stitched within the codex as decoration, and as an extra appended unbound and untrimmed set.

Occasionally there could be variations in the plates or colours, different grades of paper and bindings while – most desirable of all – were those copies dubbed hors commerce (not for sale) that, often set aside for presentation to family and friends, included original drawings, sketches or manuscript material.

All conspired to make the edition more desirable in the marketplace.

Representing the intersection of art and literature, the livre d’artiste lies somewhere between the book and the artwork.

And initially they proved of more interest to private collectors than to institutions – a reflection of the common refrain that art museums hesitate to purchase books, and few libraries can afford to acquire art. Typically artist’s books will form part of wider studies devoted to a particular artistic movement or painter.

It was not until the 1960s, by which time artists such as Dieter Roth and Ed Ruscha had moved the concept into the territory of the livre d’object, that scholarship recognised the emergence of a distinct genre.

Two US exhibitions were key: The Artist and the Book: 1860-1960 in Western Europe and the United States held at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts in 1961 and Beyond Illustration: The Livre D’Artiste in the Twentieth Century at the Lilly Library in Indianapolis in 1976. The accompanying catalogues (by Philip Hofer/Eleanor Garvey and Breon Mitchell) remain standard reference works on the subject.

Another important early study was The Artist and the Book in France (1969) by Walter John Strachan.

A teacher of modern languages in Bishop’s Stortford, Strachan had a parallel career as a poet, French translator, critic and connoisseur. His collection, amassed in repeated visits to collectors, printers, and artists over several decades, is now part of the Taylor Institution Library, Oxford.

It features several classics of the genre including Parallèlement and Balzac’s Le Chef d’Oeuvre Inconnu illustrated by Picasso (1931).

The translation of Goethe’s 'Faust' illustrated by the French Romantic artist Eugène Delacroix (published in 1828 in Paris) is sometimes cited as the first livre d’artiste. It contained a frontispiece portrait of Goethe and 17 lithographed plates drawn on stone. Delacroix was inspired to illustrate the work by a performance of the play he attended in London in 1825. Although criticised at the time, one early viewer who did appreciate their greatness was Goethe himself, who on first seeing them in 1826 wrote: “One must acknowledge that this M Delacroix has a great talent, which in 'Faust' has found its true nourishment … I have to agree that M Delacroix has surpassed the scenes of my writing.” This copy in a fine cuir-ciselé binding by Charles Meunier, dated 1920, sold for $23,000 (£17,700) in a Christie’s online sale in June 2018.

The collecting base

Are today’s buyers typically art collectors or book collectors? “I would say that many art collectors will have one or two livres d’artistes, but more extensive collections are usually the preserve of bibliophiles,” says Bonhams specialist Matthew Haley. “There are certainly livre d’artiste collectors, but very often these books form part of a wider ‘books as objects’ library which might also include a medieval Book of Hours, a volume of Piranesi, a Blake and designer bindings.”

Traditional collecting variables of rarity, condition and provenance apply but as a general rule, the higher the status of the artist, the more desirable the artist’s book.

A book that fits well into a painter’s oeuvre (such as Matisse’s Jazz) carries extra gravitas as does the collaboration that brings a good synergy of art and text.

Bindings were sometimes integral (Marcel Duchamp’s famous foam rubber breast is the most memorable element of Le Surréalisme en 1947) but others, added at a later date, are very much the stuff of personal preference.

“Some collectors want their books in their purest form, as issued and fresh off the press,” says Vincent Belloy, specialist at Christie’s Paris. “Others do appreciate them bound, adding the touch of another artist to what is already a collaborative work at heart.”

Paul Destribats

The most recent market barometer in the field has been the three-part dispersal of the Paul Destribats (1926-2017) collection held between July 2019 and February 2021 by Christie’s Paris, in association with book dealer Jean-Baptiste de Proyart and specialist Claude Oterelo.

Destribats was one of the great avant-garde book collectors of his generation, his encyclopaedic library of more than 6000 volumes, manuscripts and printed documents centred on the work of André Breton, the leader and principal theorist of Surrealism.

He has been an active buyer when several major collections were dispersed at the turn of the millennium: those of Renaud Gillet (Sotheby’s London 1999), Pierre Leroy (Sotheby’s Paris 2002), Daniel Filipacchi (Christie’s Paris 2004) and Fred Feinsilber (Sotheby’s Paris, 2006).

Some of the livres d’artistes in the Destribats collection were special copies that included original artists’ illustrations.

These included the sale-topping 1936 first-edition copy of La Barre d’appui, a volume of poems by Paul Eluard, illustrated by Picasso. His pre-war works are more desirable than those made in the 1960s and 70s. This was number one of the first six copies with proofs printed in blue, green and red that included an extra aquatint of Picasso’s right hand produced in a moment of spontaneity as the volume was printed at the end of May or the beginning of June 1936. The work soared past its high estimate of €150,000 to realise €425,000 (£386,400)

Proyart summed up the appeal of the artist book as he celebrated a €13.5m sale: “What is exciting is the fact that many of these artists created new images [for these works] that nobody had ever seen before. They invented a new way of combining paintings, books and engravings, which was something unique.”