On the face of it, parfilage, the unpicking of fine textiles to salvage the gold and silver threads, was a thrifty activity.

However, for half a century it enjoyed a vogue as a blue-blood social pastime in the courts of Europe – first at Versailles in the 1760s-70s (the name is probably derived from the French word filage, meaning to spin fibre into thread) and later in Britain from the 1790s into the Regency period where the practice was often known as drizzling.

Queen Victoria’s youngest son Prince Leopold being a devotee suggests it was done for pleasure and to display dexterity rather than financial reward. At its fashionable peak in ancien regime France, objects were made with gold or silver threads for the sole purpose of being picked apart.

The parfilage set was a luxury item. Typically made in expensive materials, it included the three necessary tools (scissors, knife and stiletto) in a case, sometimes together with a shuttle or spool onto which the metal threads could be wound.

Long-time enthusiast

A good 18th century example was included in Bleasdales’ (20% buyer’s premium) Sewing Sale held as a timed online auction in Warwick closing on June 16. Part of the first tranche of the collection of long-time enthusiast Enid Riley, the three elements with engraved silver mounts were housed in a white and blue enamel scissor style case. The final bid for this was comfortably over the £1000 top estimate at £1280.

Another word in little use today that was once common parlance is the hussif – a corruption of ‘housewife’, the name commonly given to a compact sewing kit that a soldier carried on campaign to mend his uniform.

Most of these were purely functional objects but some took on novel forms; the early 19th century example here worked in felt and silk and beadwork as a British military drummer. He wears a shako, his drum with a hinged lid for thread, his bed roll formed as a needle roll and bolster pin cushion. With only a few moth nips to count against it, this remarkable survivor from a 40- year private collection took £2420 (estimate £200-400).

This was one of several very fine examples of Georgian needlework that brought multi-estimate sums.

A late 18th century ribbon reel embroidered to one side with a flowering pansy and to the other with a flowering tree and three yellow birds took £1120 (estimate £100-200), while a delightful 18th century purse worked in red silk and silver thread as a set of bellows was a popular favourite at £2220 (estimate £150-250).

Made in a multitude of different forms, the brass needle cases made by W Avery and Sons, Redditch, and its contemporaries are among the most collectable of Victorian sewing accoutrements.

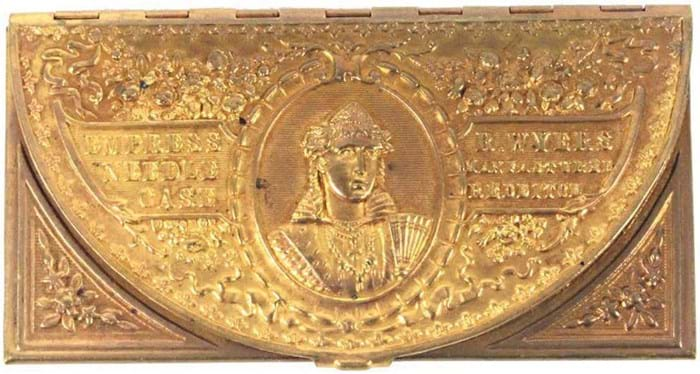

To date 226 types have been recorded – many of them available to view online at the Avery Needle Case Resource Centre. The selection offered at Bleasdales included many of the more standard types but also, sold at £340, a novel hat box form case (a design registered in 1879) and an envelope form case pressed with an image of Victoria.

Dubbed the ‘Empress Needle Case’ the latter is further inscribed verso Richard Wyers Improved Patented Needle Case – Furnished with Superior Cast Steel Sharps With Improved Elongated Eyes And Unsurpassable Temper And Polish.

Wyers, better known as a maker of fishing tackle, was also based in Reddich.

A rarity several collectors did not own, it was competed to £1220.

Take Tunbridge

Tunbridge and related wares are another element to these sales.

Rarities here included a 7 x 4in (18 x 9cm) rosewood box set to the lid with a mosaic panel of a cottage within two geometric borders sold at £1520 (estimate £100-200) and a handkerchief box in the distinctive ‘jigsaw’ marquetry pioneered by Robert Russell at £1420 (£80-120).

Russell was one of three Tunbridge ware makers whose work was shown at the Great Exhibition of 1851 (the others were Edmund Nye and Henry Hollamby). He advertised himself as ‘as inventor and sole manufacturer of the beautiful work analogous to the Tonbridge ware, but of superior character’.

Just as in Tunbridge Wells, in Killarney makers of marquetry souvenirs using local timbers including the distinctive arbutus would invite the visiting public to inspect their craftsmen at work to encourage tourists to purchase goods. One, James Egan, even introduced caged mountain eagles in his upper room as a further attraction.

The inlaid scenes of local tourist spots were based on engravings in guidebooks and topographical works of the area. A 9in (22cm) high Killarney ware arbutus wood inlaid casket, c.1850, offered here included, to the lid, a central panel of Glena Cottage, Co Kerry. As part of the collection of Enid Riley, it took £1020.