I wrote to you in August about the MA (Antiques) course run by the University of Central Lancashire (UCLAN). I wrote my dissertation for this excellent course on the Brynmawr Furniture Company Ltd, which was started in 1929 by the Quakers, and led by a master cabinet-maker, Paul Matt.

It was Paul’s father Otto (known as Charles) Matt who led the team of craftsmen working on the furniture for No 78. They were, as your piece says, ‘working on the Isle of Man’ – in fact, they were German internees, rounded up in 1915 in the face of suspicion and hostility. The island had a large camp built for them at Knockaloe.

Otto Matt had moved from Stettin in Germany in the 1880s and lived in Willesden Green in London. He is described in the 1911 census as a ‘foreman cabinet-maker’, and was in charge of a workshop of about 80 men in ‘one of the large London firms’. No-one (so far!) has been able to establish which firm this might have been. He and his brother Ernst, also a cabinet-maker, were incarcerated at Knockaloe in late July 1915 and there he assembled and trained a sizeable workforce [also see our separate story for more information].

A Quaker crafts teacher, James T Baily from Sheffield, became supervisor at Knockaloe. Baily was a friend of Wenman Bassett-Lowke, the owner of No 78; through Baily, he gave the Knockaloe craftsmen work building model ships to be used by the Admiralty. Baily wanted ‘his’ craftsmen to have a chance at building the furniture for No 78. Bassett-Lowke chose Mackintosh as designer for the house and furniture.

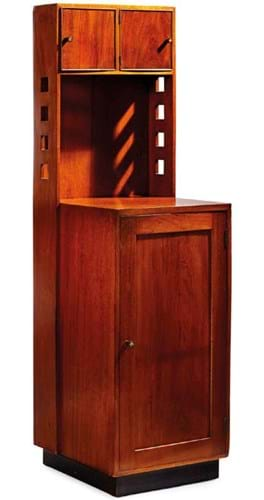

Mackintosh produced working drawings to be taken to the men; Baily then set them to work, finding good materials for them to build the quality furniture. I have no photographic evidence of the recently sold bedside cabinet being made at Knockaloe, but much of the house’s furniture was. Charles Matt’s men made cabinets, clocks, a long settle for the hall and many other items.

As your piece says, Mackintosh was ‘unable to supervise’ the manufacture – he was not one of those allowed into the internment camp. His drawings were prepared so carefully that he did not have to be there. Some of the furniture was reconstructed in 2005 by Prof Jake Kaner, who commented that the lack of Mackintosh’s personal presence was made up for by the excellent craftsmanship the men could provide.

Incidentally, the letter censor at Knockaloe was one Archibald Knox…

After making the furniture for No 78 the Knockaloe men – German and Austrian internees – made a huge quantity of furniture for homes and schools in France that had been bombed.

After the war Charles was allowed to return to his family in London. Ernst, sadly, was repatriated to Germany, against his wishes.

Quakers in Brynmawr

Charles trained his son Paul as a master cabinet-maker. They both became Quakers. In 1929 the Quakers began work in Brynmawr and called for help; Paul said to the organiser that he ‘could make furniture’, and was set to work.

By 1938, around 50 people were still making furniture at Brynmawr, but the Second World War stopped work. Brynmawr furniture, built in very difficult circumstances, was made to Paul’s – and Charles’ – high standards. It is still highly sought-after and sells regularly at auction.

Fascinating links between the Matts, Bassett-Lowke and Mackintosh!

Dr Jen Llywelyn

Bwlchygroes, Sir Benfro