“Talk across the industry now is just how much a game changer the pandemic will prove to attitudes and behaviour. It’s quite clear that those who might have taken another five years to become comfortable with viewing and bidding online have now taken the leap. Having been successful in their efforts, they’ll be back.”

Chris Ewbank, a past chairman of the Society of Fine Art Auctioneers & Valuers, and an auctioneer of more than 30 years standing, pondered the future of his profession in the wake of a 225-lot Asian Art auction on April 30.

Although the sale was conducted at Ewbank’s (25% buyer’s premium) Burnt Common saleroom behind closed doors with no opportunity to view in person – anathema to the ‘proper’ way of studying Chinese works of art – live online bids were successful on all but a handful of the 96% of sold lots.

At just over £160,000 hammer the sale total was more than five times the estimate.

Some sellers had been nervous and reluctant to accept the sort of cautious estimates that attract suitors in all auction formats.

“I had to speak personally with a number of important consignors to reassure them,” said Ewbank.

“In one case, the recipient of several dozen pieces from a deceased estate was vehement that the auction should not go ahead, but eventually came around.

“After the event, they emailed to tell me how delighted they were with the result.”

Many auctioneers regret the way it is going, but I believe it is a case of adapt or die

Not period but desirable

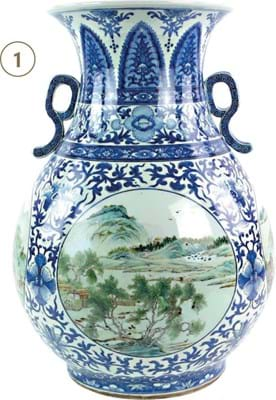

Top lot in the sale was a large 22in (55cm) high underglaze blue and famille rose decorated vase, decorated with circular landscape vignettes.

It carried a six-character mark for the emperor Qianlong (1735-96), and had it been 18th century it would have been priced comfortably into six figures, but it was not of the period.

It nonetheless sold as a 20th century decorative object for £20,000 against an estimate of £500-1000. The winning bid came from China via online marketplace thesaleroom.com.

Also selling via thesaleroom.com was a part service of 13 famille rose plates of two different sizes, each decorated with a pair of phoenix. They had Guangxu (1871-1908) six-character marks, but as these too were deemed apocryphal the estimate was just £80-150. In fact, the winning bid was £8500.

The same hammer price was bid – this time against an estimate of £400-600 – for a distressed Qing kesi robe embroidered with a five-clawed dragon to a blue ground, while £9000 (estimate £200-400) was required to win two large Ming type green and blue glazed pottery figures. The taller of the two figures, one holding a large vase, the other balancing on his right foot, stood 4ft 6in (1.37m) high.

Change is coming

Ewbank said that, as similarly positive results are replicated across the regional auction spectrum, “the debate over the future shape of the industry is already well advanced”.

As some traditionalists still prefer viewing and buying art and antiques in person, he concedes more change in favour of the online selling model is unlikely to be universally popular.

“This is a very controversial situation and many auctioneers regret the way that things are going, but I believe it is a case of adapt or die,” Ewbank added.

“Perhaps we needed a jolt to move away from the rather stuffy and elitist image that conventional auctions have. Many of us will be looking at how we continue to develop our businesses once the crisis is over.”