In its current show Stoppenbach & Delestre divides the career of artist André Derain (1880-1954) into four periods of equal weight even though, for many buyers, only the first is important.

The French painter is known chiefly as co-founding the Fauvism movement with Henri Matisse (1869-1954). Running from c.1905-10, the style emphasised strong colour over realistic detail. It was a radical moment in the development of Modern art, and it is from this early period that Derain’s top-selling works come.

These include Arbres à Collioure, a 1905 oil that sold for a premium-inclusive £16.28m at Sotheby’s London in 2010, where it was catalogued as representing “the pinnacle of Derain’s career as well as of the Fauve movement”.

Later value

However, according to dealer Robert Stoppenbach, plenty of merit is to be found in the artist’s output beyond this narrow period.

“His values are all over the place,” he says. “The Fauves – that’s him in art history. But you can buy a good late oil for £20,000.”

André Derain: From Fauvism to Classicism runs until February 21 in the St James’s gallery and comprises 22 paintings and 11 works on paper. Prices range from £3000 for drawings to £1m and up for paintings.

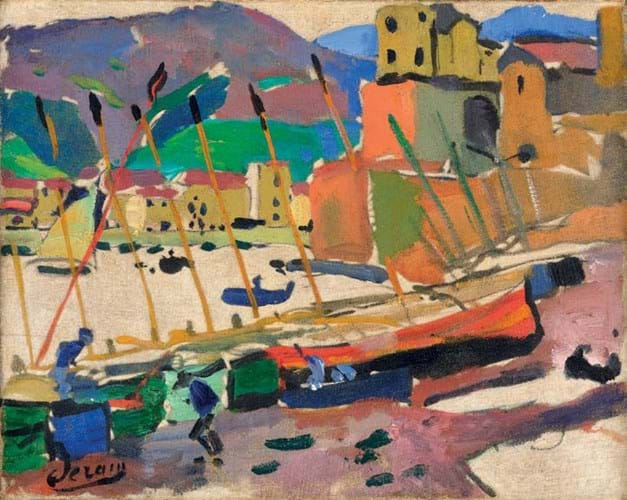

Beginning with early works such as Le Port de Collioure (1905) and Bateau au Port de Collioure (1905), the gallery offers several paintings from each stage of the artist’s career, often demonstrating how changes in his output reflect the development of Modern art.

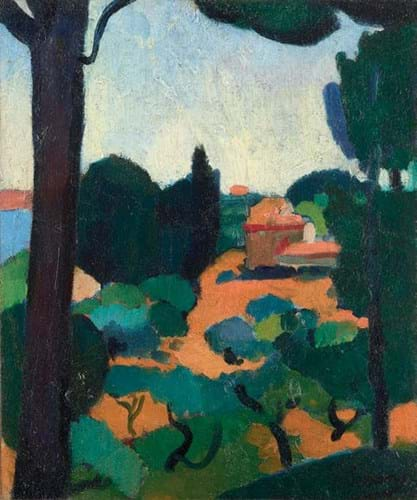

He started to drift away from Fauvism in 1906. His 1907 landscape Paysage à Cassis is an early example of his second phase or ‘Cézanniste’ period (c.1907-10) and reflects how Derain combined vivid hues with an awareness of other artists’ works.

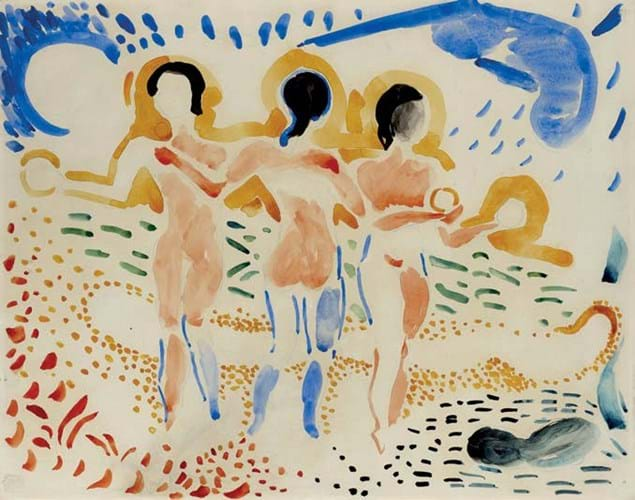

The third phase in the show is his ‘return to order’, part of a wider movement in Europe after the First World War. Following Derain’s war service, his paintings were marked by muted colours and softer forms, influenced by the work of earlier artists and the Old Masters.

By the 1920s he was regarded as one of the foremost French painters and for the next two decades he experimented with form and colour, producing portraits, landscapes and works informed by the Classical world.

Great promoter

Four of the works in the show are from the collection of the artist’s dealer, Paul Guillame (1891-1934). He did much to advance Derain’s career through exchange of ideas and advocacy.

“He was a great promoter,” Stoppenbach says, adding that Guillame’s death in 1934 may have contributed to the artist’s reputation being “somewhat eclipsed” in the minds of the public. By the time he created his late works (the fourth and final period in the show), Derain had distanced himself from the art world, but continued to produce rhythmic compositions in harmonious colour.

Each phase may be superficially different, but all are underpinned by the artist’s interest in colour and other artistic movements.

Today Derain’s work is mostly exhibited in Europe. According to the gallery, which has a long history of representing the artist, this is the first major show of his work in the UK for more than 15 years.

When the business opened in 1982, its first sale was a picture by Derain which went to the Tate. Stoppenbach is now on the André Derain committee and is in possession of possibly the largest collection of works by the artist in the world.

An associate of many leading artists in his day – from fellow Fauves Matisse and Vlaminck to Balthus and Giacometti later – Derain continues to inspire artists.

Cry freedom

Among his admirers are Scottish painter Merlin James, who writes in the catalogue introduction for the show: “He touches nerves. He was at once compromising and capricious. He insisted on absolute artistic freedom, including the freedom to accept restrictions and recognise standards, if only to then bend the rules again.”

Stoppenbach, too, attributes Derain’s appeal to his spirit of artistic independence. “He didn’t reject earlier works,” he says. “He wasn’t reactionary, but he went his own way.”