Three of the objects chosen for the October campaign were long-time exhibits from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and had been misrepresented. Other pieces came from stock image sites and had not been stolen.

CINOA, the international federation of art and antiques dealers associations, filed a formal complaint with Unesco on November 15. It described the campaign as “fraudulent, with the desired intention to mislead the public on the provenance of works of art and to damage the credible reputation of the art trade and collectors.”

Unesco launched its ‘The Real Price of Art’ campaign with agency DDB Paris on October 20 “to make the general public and art lovers aware of the devastation of the history and identity of peoples wreaked by the illicit trade in cultural goods”.

It marked the 50th anniversary of the Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property adopted in 1970.

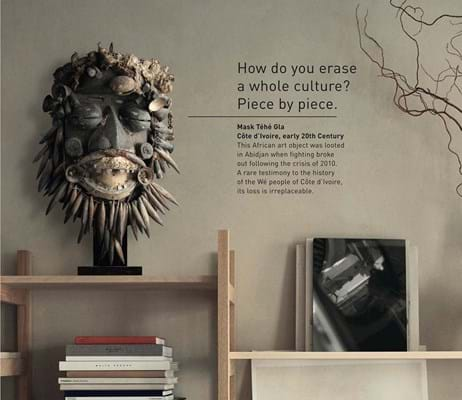

Five adverts were created, each picturing an object copied into the living room of an art collector, telling the story of antiques stolen in the Middle East, Africa, Europe, Asia and Latin America.

Adverts pulled

However, by mid-November, Unesco had pulled back the posts after it emerged only one of the five objects used in the campaign – the Righteous Judges panel from the Ghent Altarpiece missing since 1934 – had actually been stolen as the text suggested.

Members of the International Association of Dealers in Ancient Art quickly identified three of the pieces as those in the Met collection and another (a pre-Columbian face jar) that had been sourced from commercial image bank Alamy.

For example, the image of a 5th or 6th century Hadda stone head of Buddha was pictured alongside the headl ine ‘Terrorism is such a great curator’ and the text ‘This antiquity belongs to the Kabul Museum. In 2001, a large part of its collections was smashed into pieces by the Taliban. As the group was overthrown later that year, this priceless item was looted by local dealers and smuggled into the US market.’

In fact, excavated during the 1927-28 Trinkler expedition, it has been in the Met’s collection since 1930.

Similarly, a funerary monument from Palmyra was said to have been ‘stolen by Islamic State militants during their occupation of the city, before being smuggled into the European market’ while a Baule moon mask from the Ivory Coast region was accompanied by the information it had been ‘looted in Abidjan as fighting took place following the electoral crisis of 2010-11’.

More correctly, the Palmyra relief had been in the Met since 1901 and the mask in private hands since 1954.

In a statement on its website, Unesco said it “regrets the use of Met images that caused any misunderstanding”.

It read: “In an initial version of Unesco’s campaign, the ‘Real Price of Art’, some posters displayed items from the Metropolitan Museum of Art database that is in the public domain.

“Unesco’s intention was to alert the general public by depicting objects of high cultural value, which should be on display in museums, presented in luxurious private interiors. Unesco had no intention of questioning the provenance of items in the Met collection.

“After discussions with the Met, which is a valuable partner to Unesco, and in order to avoid any misunderstanding, Unesco decided to remove all pictures of items from the Met collection. Only three magazines [carrying the adverts] had already been printed. The digital versions of these publications were modified.”

IAADA, which has long questioned Unesco’s claims regarding the scale of the looted art problem, points out that copies of the original posts are available on multiple sites online.

The association also contends that some of the items used as replacements also amount to fabrications.

The Met’s Baule moon mask was replaced by an early 20th century Téé Gla war mask with the text again saying it had been looted in Abidjan in 2010. However, IAADA tracked the piece to the city’s Musée des Civilisations and contacted the curator who confirmed it had not been stolen and remained in the collection.

IADAA’s spokesmen told ATG: “Unesco keeps claiming that evidence of trafficking involving the art market is so widespread and clear. If so, why persist in publishing false information and go to such lengths to do so? Why not simply publish the real evidence instead?”

‘The real issue’

Asked to comment, Unesco told ATG: “The use of all images and texts of the current campaign were discussed with all institutions concerned.

“The artworks shown were all stolen or reported missing at some point, some are still categorised as stolen or missing (Africa, Europe) but for others (South America and Arab States) we have used restituted artworks, and this is noted in the text, either explicitly or implicitly.

“We would prefer to discuss the real problem – art trafficking and how to tackle it effectively. The illicit trade in cultural property has exploded in recent years – this is the real issue.”

Picture change

When first published in October, this Unesco poster titled ‘How do you erase an entire culture? Piece by piece’ featured a Baule moon mask (above) from the Met collection.

Using the same text detailing the theft of the piece from the Ivory Coast capital during a political crisis, a second version of the poster was created to include a Téé Gla war mask (above) from the We Guéré people. However, it too has not been stolen and remains in the Musée des Civilisations in Abidjan, Ivory Coast.

Unesco told ATG: “The use of the image of the African mask, as well as the text, were discussed and agreed with the museum, a long-standing partner that fully supports our campaign.”