More than 2500 coins were discovered in January 2019 by a group of metal-detectorists on land south of Bristol, which the British Museum said makes up an “unprecedented opportunity to examine changes in the coinage in the immediate aftermath of the Norman Conquest”.

The find almost doubles the number of known Harold II coins and includes five times more examples of the first coin type issued by William I than previously identified.

The BM also said that early analysis indicates the presence of mints previously unrecorded, including coins of Harold from the local mint of Bath.

The Roman Baths & Pump Room in Bath has expressed interest in acquiring the hoard for its collection.

Now to be known as the Chew Valley hoard, it also includes the first known examples of a ‘mule’ coin between Harold and William. Mules feature a design from different coin types on each side of the coin, indicating that the moneyer re-used a die to create one side - an early form of tax evasion. The BM said: “The mule demonstrates that coins were produced with Harold II's name on after William I had taken control of the country following the Norman Conquest and established coinage of his own.”

The hoard also includes a rare example of a mule of Harold’s predecessor Edward the Confessor (1042-66) and William I.

Following the discovery, the coins were taken to the BM where they were cleaned and catalogued for a report for the coroner to examine whether they are treasure under the Treasure Act. The act gives museums the opportunity to acquire finds. Administered by the BM, the items will be valued by the independent Treasure Valuation Committee and the finder and owner of the land where the coins were found can claim a reward. Museums then have the chance to raise funds to acquire the coins.

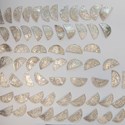

The hoard, said to be in “good condition”, is made up of 1236 coins of Harold II and 1310 coins of the first type of William I, as well as a number of fragments.

Commenting on the hoard, Nigel Mills at coin specialist Dix Noonan Webb said in the firm’s opinion the coins could be estimated at £3m-4m. He said: "At DNW, we have sold a Harold II penny of Lewes in July for £3000 and for the first type of William I, we sold a Winchester mint for £1300 in July… My estimate for the hoard is based on £2000-4000 for the Harold II coins and £1000-1500 for the William I. Adding up the numbers here at DNW we estimate it at £3m-4m … if they were to come to market.”

Gareth Williams, curator of early medieval coinage at the British Museum, said: “This is an extremely significant find for our understanding of the impact of the Norman Conquest of 1066… the coins will help us understand how changes under Norman rule impacted on society as a whole.”

Councillor Paul Crossley, cabinet member at Bath & North East Somerset Council, said: “We are very excited about the discovery of this important hoard in north-east Somerset with such strong connections to our area. If we are able to acquire the coins, we will work to display them locally, as well as partnering with the British Museum to make them available for loan… so they can be seen by a wider audience.”

Most of the Harold coins in this group were produced in Sussex and the south east, which the BM said indicates “financial preparation in the area to resist the Norman invasion”.

Period of unrest

The exact circumstances in which the hoard was buried are uncertain. The BM believes the hoard was buried in the period c.1067-8 which was a period of unrest in the south-west.

In 1067 the Welsh attacked Herefordshire and in 1068 William besieged Exeter. Later the same year the sons of Harold returned from Ireland, raiding around the mouth of the Avon, in Bristol and into Somerset.

The BM believes it is this event that is the most likely to be directly associated with the hoard, but all three episodes could have led to significant wealth being buried for safety.