If there was a year when the market for Qing and later Chinese silver changed it was 2005.

A scholarly exhibition titled Chinese Export Silver: The Chan Collection had been held at the Asian Civilisations Museum in Singapore, showcasing a collection assembled since the 1980s by local ‘early-bird’ collector David Chan.

It was announced shortly after the exhibition closed that all pieces had been sold to a mainland Chinese buyer, lock, stock – and dragon.

As London Silver Vaults dealers Stephen and Jeremy Stodel of S&J Stodel recall, it had not always been that way.

“When we began 43 years ago we were looking for something we could afford at a time when prices for traditional antique silver were very high. Typically the price of mid to late 19th century Chinese silver hovered around the melt value. We believed it was a hugely decorative product that was underrated.”

At the time there were just two other dedicated dealers: Fortunoff (New York) and Glenn and Lucille Vessa of Honeychurch Antiques, the ‘king and queen’ of Hong Kong’s Hollywood Road in its 1970s-80s pomp.

Art historical information had been hard to come by. Unlike other aspects of Chinese art (the subject of some of the earliest Western reference works on antiques), the field was not seriously studied until the late 1960s. The first book on the subject, Chinese Export Silver 1785-1885 by Massachusetts collector and academic Dr Henry Ashton Crosby Forbes, was not published until 1975.

In short, says Stephen Stodel, “until the 1980s most late-19th century Chinese silver was sold as style accessory rather than serious antique”.

Distinct eras

Chinese export silver can be imperfectly split into two distinct eras – those pieces made before and after the Treaty of Nanking in 1842.

The earlier period is characterised by both the splendid filigree work admired by the imperial courts of Europe (Catherine the Great and Queen Charlotte were both avid collectors) and nearslavish copies of Georgian silver created on the cheap for British merchants, sea captains and crew. Typically, as China mined relatively little silver of its own, the melting of trade dollars and silver ingots (sycees) provided the raw material.

A contemporary insight is provided by Osmond Tiffany, author of The Canton Chinese or The American’s Sojourn in the Celestial Empire (1849), who wrote: “The silver is remarkably fine, and the cost of working it is a mere song. Its intrinsic value is of course the same as it is in Europe, but the poor creatures who perspire over it are paid only about enough to keep the breath in their bodies.

"It is much cheaper to have a splendid service of plate in China than in any other country, and many Europeans send out orders through supercargoes.”

Among the earliest-known Chinese export silver teapots is a small group made for import into England in the late 17th century. One example carries London hallmarks for 1682, in compliance with the law that foreign silver should be marked at Goldsmiths’ Hall before it could be sold in England. In September 2018 this rare 17th century Chinese silver ewer was acquired by the Palace of Versailles in a private treaty sale conducted by the auction firm Beaussant Lefèvre. It is the only known surviving piece of silverware from a lavish diplomatic gift presented to Louis XIV by the King of Siam (Thailand) in 1686. (Photo copyright Studio Sebert - Beaussant Lefevre.)

Pseudo hallmarks

Some of this ‘splendid plate’ – dubbed ‘China Trade silver’ – came with pseudo English hallmarks that have long amused academically-minded Western collectors.

An oft-quoted example is the enigmatic Canton workshop stamping its wares WE WE WC in imitation of the London spoon maker William Eley, William Fearn and William Chawner. The Goldsmiths Company Assay Office was occasionally prone to having such pieces destroyed as fakes.

The Treaty of Nanking in 1842 that ended the arcane Canton system of trade acted as the catalyst for the growing fashion for chinoiserie in Europe and North America.

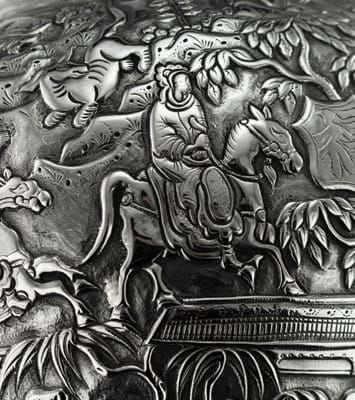

The forms remained unquestionably Western but the appearance of Chinese-made silver began to change in favour of native decorative motifs such as bamboo, chrysanthemums, orchids, plums, cranes, dragons and figural scenes of mythology and military history. The appeal is the fusion of cultures.

Home and away

Not all of it left China. Many pieces of Chinese ‘export’ silver were presented as gifts or prizes for the gentlemen’s and sporting clubs that became synonymous with Westernisation in Shanghai and the crown colony of Hong Kong.

Similar examples of européenerie found favour among an emerging middle class or added theatre to the grand tea parties held in the Treaty Ports to impress Western merchants.

Added to this is the silver made by immigrant Chinese in the vassal states or the Peranakan silver made in Malaya and Singapore for the baba-nyonyas, the ethnic Chinese populations of the British Straits Settlements.

For these reasons there are academics who would prefer to talk simply of ‘Qing dynasty silver and Chinese Republic silver’.

Scholarly interest in the subject has doubtless been piqued by a market that has moved forward in leaps and bounds.

No longer is Qing silver vulnerable to the spikes in the bullion price as it was for most of the 20th century. It is the buying audience that has changed.

Once the preserve of an American fan base charmed by the exotic, the flamboyant and the downright showy, by the 1990s buyers had also emerged from Hong Kong and Singapore and in the 21st century mainland Chinese collectors began to take note.

“We received our first online enquiry from China in 2004,” recalls Stodel. “By 2006 prices were rising exponentially and they have rarely softened since.”

The market continues to evolve. Chinese collectors show a preference for traditional motifs, enamelled wares and silver gilt while some forms are more popular than others.

“The first piece a Far Eastern buyer will purchase is a tea set. The first piece a Westerner will want to own is a beer mug,” says Stodel.

A recent development is the focus on particular makers or cities of production. Not until the past decade have scholars attempted to produce anything like a comprehensive study of the marks which is now allowing collectors to identify and group objects by style, region and producer with more confidence.

Retailers and makers

A breakthrough was the understanding that most of the late 19th century ‘makers marks’ mentioned by Crosby Forbes are in fact simply merchant houses or retailers.

It is only by deciphering the Chinese characters or chop marks that accompany the Latin alphabet initials and numerical guides to metal purity that the names of actual silversmiths are found.

By way of example are the many pieces carrying initials for Wang Hing – the best known and most prolific ‘maker’ in the late Qing and early Republican period which exhibited at international exhibitions and enjoyed connections with firms such as Tiffany.

The name Wang Hing, simply a portent to good luck and success, more properly describes a luxury goods emporium with outlets in Canton, Shanghai and Hong Kong that provided work for a network of hundreds of silversmiths – many of them working as ‘free agents’ for a number of different paymasters.

The most recent research on the topic is being led by Adrien von Ferscht, author of Chinese Export Silver 1785-1940, The Definitive Collectors’ Guide, a fellow of the University of Glasgow and Tsinghua University, Beijing, and consultant to museums and auction houses.

His desire to place Qing and later silver in the context of over 2000 years of Chinese silversmithing is helping to change the way pieces are catalogued and how they are interpreted by the buying audience.

“Picking up a piece of Chinese export silver is tantamount to holding a hand grenade packed with history, culture and artistic merit,” he writes. “It is ready to explode and reveal its secrets.”

CHINESE EXPORT SILVER: A COLLECTING TIMELINE

- 1964 Inspired by a family history that included 11 members of the China trade, Dr Henry Ashton Crosby Forbes opens the Museum of the American China Trade in Milton, Massachusetts. It is renamed the Forbes House Museum.

- 1975 The Museum of the American China Trade publishes Chinese Export Silver 1785-1885 by Crosby Forbes (with John Devereux Kernan and Ruth Wilkins). For many years it is the definitive volume on the subject.

- 1985 The first major exhibition of Chinese export silver was held in New York to mark the 75th anniversary of the Ralph M Chait Galleries. A catalogue, The Chait Collection of Chinese Export Silver, is written by John Devereux Kernan.

- 1990 Venerable London Chinese art dealership John Sparks holds an exhibition titled A Survey of Chinese Export Silver. The catalogue is written by ex-Foreign Office diplomat Alan Marlowe.

- 1997 The handover of Hong Kong iin July 1997 is marked by a football match held between Chinese and British Hong Kong teams. The winner’s trophy, an elaborate late-19th century Chinese silver cup and cover, was supplied by S&J Stodel.

- 2005 The exhibition Chinese Export Silver: The Chan Collection is held at the Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore. David Chan had been collecting Chinese export silver since the 1980s. The collection, much of it originally purchased from S&J Stodel, was later sold in its entirety to a mainland Chinese buyer.

- 2013 Chinese Export Silver of the Qing Dynasty, 1685-1940 is published by Adrien von Ferscht. A fifth edition of this catalogue of around 500 silversmiths, silver-making workshops and retail silversmiths operating in imperial and republic era China in the 18th, 19th and first half of the 20th century, will be published shortly.

- 2018 An exhibition The Silver Age: Origins and Trade of Chinese Export Silver is held at Hong Kong Maritime Museum.