Since the sale of ‘America’s oldest china teapot’ to the Metropolitan Museum of Art last year for £460,000, Woolley & Wallis (25% buyer’s premium) has been approached with a variety of pieces that fall outside the recognised corpus of English blue and white porcelain. Vendors are hopeful that they too may own a piece of porcelain made by John Bartlam in Cain Hoy on the Wando river in South Carolina c.1765.

Of these, says specialist Clare Durham, “some have been completely discounted, some have been scientifically tested and then discounted, and some are still undergoing research”.

And two pieces – representing the eighth and ninth recorded pieces of the earliest porcelain made on American soil – emerged for sale on February 19.

All pieces of Bartlam have so for been found in England. The newly discovered matching tea bowl and saucer had been acquired for under £1000 on eBay within the last two years by a collector who was playing a hunch that an attribution to the Isleworth factory might just be wrong.

The transfer-printed design is the same version of the Man on the Bridge pattern that appeared to one side of the teapot and testing has since confirmed the paste matches that of the sherds dug at the Cain Hoy site in 2007.

What price would it bring?

There were hopes of another six-figure sum (a single teabowl in the Bartlam on the Wando pattern was sold by Christie’s New York in 2013 at $120,000/£76,000) but it took an immediate aftersale to get it away for ‘only’ £40,000. It will go to an American buyer who was acting through London porcelain dealer Rod Jellicoe (agent for the Met last year).

Durham, head of European ceramics and glass, felt that several factors were at work – in particular, the finite number of collectors and institutions with the funds to hold prices at hitherto stratospheric levels.

In hindsight we placed too much emphasis on ‘English collecting rules’ – these pieces are so rare that condition becomes irrelevant

“In hindsight we also placed too much emphasis on ‘English collecting rules’ that put a premium on a matching teabowl and saucer and good condition. In fact, these pieces are so rare and esoteric that (as with the teapot) condition becomes almost irrelevant.”

We await the discovery of piece number 10 with interest.

The emergence of North America as a new frontier in connoisseurship is a reminder of just how much remains uncertain in the 18th century porcelain field.

In March last year dealership E& H Manners held a selling exhibition of porcelain figures assembled over 25 years by British Columbia collector Roy Hogarth. It focused on figures from the rarer factories and those that defy easy categorisation.

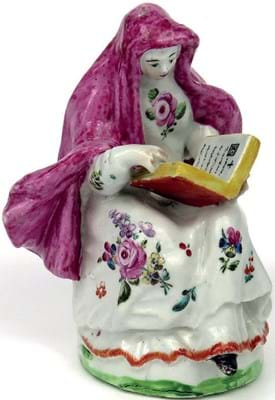

Some of the residual pieces were offered for sale in Salisbury, including a London-decorated figure of a seated nun c.1755-60, after the model by Bow (and ultimately Meissen), that remains something of an enigma.

The steatic soft-paste porcelain of this model has been previously attributed to Vauxhall but may possibly be linked to a short-lived concern at Kentish Town under the direction of John Bolton. It sold for £1500 (estimate £500-800). A similar figure is in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

An early Bow white-glazed figure of a huntsman filling the powder flask, his dog seated by his right knee, c.1752-53, took £2000 (it had a chip to the base and the end of his gun was lacking).

Sold for £3900 was a Chelsea figure of a dancing Dutch peasant c.1752-53, after a Meissen model by Kändler (with some good restoration).

The latter had been sold at Bonhams in 2010 for £2000 and had later formed part of a Simon Spero exhibition for which Hogarth, fresh from a flight from Canada, queued diligently for nearly 30 hours.

Watney enamels

A number of small collections enlivened the Salisbury sale.

A group of 18th century Birmingham and Battersea enamels collected by the late Bernard Watney were entered for sale by his widow.

Like much of Dr Watney’s vast holdings of English porcelain (dispersed in a famous series of sales by Phillips and Bonhams), they had been bought to educate and appreciate as much for display. But if condition sometimes left something to be desired, modest estimates and academic appeal ensured plenty of competition.

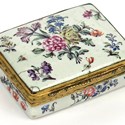

Sold to a collector for £3000 (estimate £150- 200) was a small 2in (5cm) rectangular patch box c.1770 with gilt meal mounts finely painted with flower arrangements and single scattered sprigs. It was probably the best-preserved of the 15 pieces.

A Birmingham panel c.1760, finely painted with butterflies, damselflies and two green backed beetles, sold for £1600 (estimate £100- 200). It was probably once a box lid and had some cracking and chipping. Despite cracks and losses, a Battersea snuff box c.1750-55 with puce engravings by Simon Francis Ravenet (1706-64) took £550 (estimate £200-300).

An identical box, printed to the top with Britannia Surrounded by the Arts and Sciences and to the interior with a portrait of Frederick, Prince of Wales, is pictured in Susan Benjamin’s book English Enamel Boxes.

A series of oval portrait plaques included one, 3in (8cm) high, printed in manganese with a halflength of Samuel Reddish (1735-85) in the role of Young Bevil. The print is taken from a 1777 engraving in Bell’s British Theatre of Reddish in his role in The Conscious Lovers. It had some cracking but took £650 (estimate £300-500).

Reddish, an actor, director and West End theatre manager from Frome who played Macduff opposite Garrick’s Macbeth in 1767, is recorded as dying in an asylum in York.

Elements from another private collection – that of the Australian collector Nigel Morgan – yielded the top price in the room.

Like many Chelsea bird models, the design for a rare model of a fieldfare c.1750-52 follows a print by the ‘father of British ornithology’ George Edwards (1694-1773). The floral decoration was probably added by an outside London atelier and is similar to that found on pieces from the St James’s factory run by Huguenot jeweller Charles Gouyn (another factory not firmly identified until 1993).

Birdie’s Chelsea fieldfare

It carried a paper label for the collection of Lady Ludlow (1862-1945), whose collection of English and continental porcelain – including many ornithological subjects (her nickname was ‘Birdie’) – was acquired by the Bowes Museum in 2004.

Despite some restoration to the beak, it attracted multiple admirers at its £600-800 estimate and sold to the trade at £9000.

Several pieces from this collection (elements of which had been sold by E& H Manners a decade ago at the International Ceramics Fair and Seminar) had formed part of Flowers and Fables: A Survey of Chelsea Porcelain 1745-69, an exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria in 1984-85.

A Limehouse blue and white scallop shell pickle dish c.1746-48 – £2800 at Woolley & Wallis in Salisbury.

These included both a two-figure group of the Peasants’ Supper modelled by Joseph Willems after Meissen c.1755-58 (estimate £1000-1500) and a naturalistically modelled sunflower pot with cover and stand c.1755 (estimate £1000- 1500). Both with minor faults and the latter with restoration to the cover, they took £5000 and £4200 respectively.

The sale totalled £220,000 with 79% of the 309 lots sold.