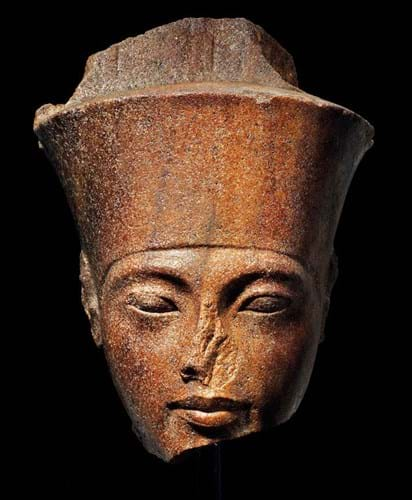

It follows the Egyptian National Committee for Antiquities Repatriation saying it will instruct a UK law firm to file a case over the auction of a bust of Tutankhamun at Christie’s on July 4. It called on Interpol to track the statue and other artefacts which it claims have been sold without the correct paperwork.

Prior to the sale, Egypt had questioned “the legality of trading in these items, the authenticity of documents, and evidence of legal exportation from Egypt”, but Christie’s has countered stating that it “carried out extensive due diligence”.

Chairman of the ADA Joanna van der Lande said that Egypt’s claim was part of a “wider zeitgeist” of nations attempting to reclaim works found on the antiquities market.

“Auction houses have been fielding claims from archaeologically rich countries for decades,” she said. “With the increased online presence and transparency of both dealers and collectors they too are now being targeted.

“In the case of Egypt, they had a thriving antiquities market for over 100 years when they finally made it illegal to export antiquities in 1983.”

Complex history

Van der Lande pointed out that a complex sharing system used in the past – where foreign excavation teams worked with government museums to share archaeological finds with no legal obligation to retain invoices and documentation –meant that legally exported antiquities were now becoming unfairly tainted.

“What is important now is that the market continues to tighten its due diligence practices – which it has been doing in recent years – and that it also stands up to the politicisation of the trade.”

This latest development follows Turkey’s decision to pursue legal action over the $12.5m (£9.7m) sale of the Guennol Stargazer, an ancient Anatolian idol, at Christie’s in New York in 2017 and the demand last year from Greece that a Corinthian Geometric period bronze horse at Sotheby’s be returned.

Before the sale of the Tutankhamun head, Christie’s published a 50-year collecting history that indicated the piece had been in Germany, probably first in the collection of Prinz Wilhelm von Thurn und Taxis (1919-2004), since the 1960s.

In responding to the legal threat, the auction house issued a statement saying that it “clearly carried out extensive due diligence verifying the provenance and legal title, establishing all required facts of recent ownership”.

Christie’s also questioned why Egypt had not raised doubts about the head when it had been exhibited in the past.

It added that it would not and does not “sell any work where there isn’t clear title of ownership and a thorough understanding of modern provenance”.

“We recognise historic objects can give rise to complex discussions about the past; our role is to provide a transparent, legitimate marketplace upholding the highest standards for the transfer of objects from one generation of collectors to the next.”

Full statement from Joanna van der Lande, Chairman of Antiquities Dealers’ Association

“The Egyptian claim on the head sold at Christie's is part of a wider zeitgeist where nations rich in cultural heritage reclaim works found on the antiquities market. This pre-dates the horrors inflicted by Isis on the cultural heritage of Iraq and Syria. “Auction houses have been fielding claims from archaeologically rich countries for decades and with the increased online presence and transparency of both dealers and collectors they too are now being targeted. In the case of Egypt, they had a thriving antiquities market for over 100 years when they finally made it illegal to export antiquities in 1983.

“In addition there was a complex partage system where foreign excavation teams worked with government museums to share archaeological finds. There was no obligation to retain either invoices or proof of export which came in the form of a stamp on the invoice.

“Invoices are rare documents and the few that I have seen often list multiple items, sometimes amounting to hundreds or thousands of antiquities, with no identifiable information from a pre-digital age. The absence of export documentation does not in itself taint an antiquity because there was no legal obligation to retain any such documentation.

“What is important now is both that the market continues to tighten its due diligence practices, which it has been doing in recent years and that it also stands up to the politicisation of the trade. While the Antiquities Dealers’ Association abhors any wanton act of theft or looting, the changing perception of who should own what is far more complicated as it involves long-standing chains of ownership and good faith purchases. The increased uptake on art law courses suggests this is a subject of growing interest but the interests of many must be taken into account and the rules of law, not emotion applied.”