For nine years now Christophe Lucien of the Nogent sur Marne auction firm just outside Paris has been holding his Paris Mon Amour themed sales.

These eclectic ensembles that celebrate the City of Light embrace anything from paintings, pieces of metro stations and Paris brasseries to posters and old photographs.

When he first started this series of specialist sales the majority of the bidders were foreign, recalls Lucien, notably Americans celebrating their long love affair with the city. But things have changed.

“From sale to sale Parisians have become more of a presence. Now they come en masse. Bit by bit it is as if the sales we do have opened their eyes to the heritage of their city,” he said.

This year he had something extra to mark the occasion: a single-owner collection of Paris memorabilia mixing paintings and items of street furniture taken from its buildings and roads.

It had been assembled by Roxane Debuisson, a passionate enthusiast for the heritage of Parisian streetscapes and one of the first to embark on preserving the city’s heritage before it became lost to demolition and refurbishment.

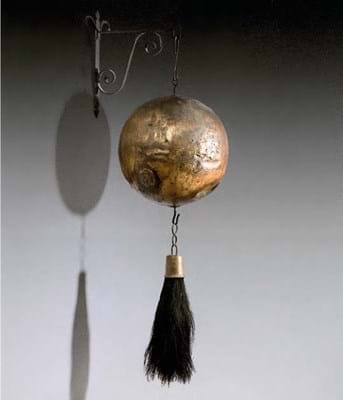

This elaborate Art Nouveau sign from the lanternmaker Grimmeisen on the rue du Faubourg du Temple was acquired by Debuisson in 1972, her attention drawn to it by Robert Doisneau the photographer. Originally gas lit, now powered by electricity, the 4ft 5in x 5ft 3in (1.35 x 1.62m) tôle and iron sign was one of the Musée Carnavalet’s purchases at €2500 (£2135). All images: Lucien/Drouot.

She amassed books, postcards and invoices, topographical drawings and paintings, elements of the boulevards and buildings – and above all, the distinctive sculptural shop signs that were once found across the city.

Scouring fleamarkets and calling in on shop owners, nothing was too humble in Debuisson’s eyes for preservation. She even bought the inter-war iron bench on the boulevard outside her home when she saw the workmen removing it for replacement. Some of these salvaging searches were made in the company of her friend, the photographer Robert Doisneau, another impassioned enthusiast for Paris’ built heritage.

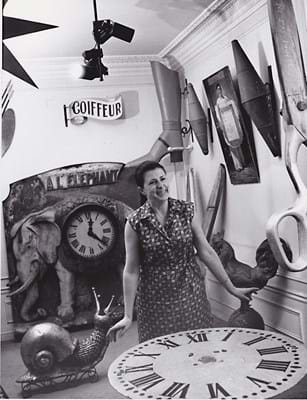

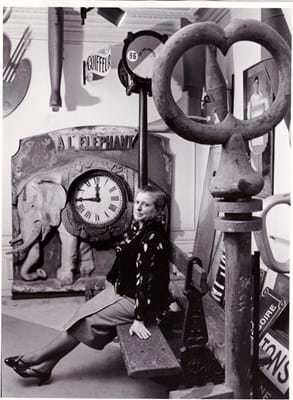

Debuisson’s finds were taken to her central Paris home where she lived surrounded by them in what her daughter Florence described as an “appartement-musée”.

They comprise a 3ft (93cm) bust on stand of the famous French playwright and two full-length figures, possibly Alceste and Don Juan. The latter date from c.1820, Molière is probably earlier. The trio cost €6500 (£5555) in the Lucien auction.

In 1970 Debuisson managed to acquire three plaster figures from the façade of the baker’s shop A Molière on the rue de Pont Neuf. All images: Lucien/Drouot.

Heritage and gastronomy

Lucien knew the collector and her family. When she died last year aged 91 he was the chosen auctioneer to sell her lovingly curated collection. What better opportunity to market this than to offer it on Monday, March 18, immediately before his ninth Paris mon Amour sale?

“Roxane had masses of friends who shared her passion,” said Lucien, but she was also well known beyond the salvage sphere. In the 1990s she developed a keen interest in French gastronomy, receiving in 1994 the distinction of Personnalité de l’année dans le Monde de la Gastronomie at the Crillon Hotel.

The auctioneer therefore already had the core of a highly interested souvenir-hunting audience on which he could build.

Estimates had been deliberately set at modest levels. This was partly to encourage interest and, said Lucien, to make it affordable to the maximum range of purses. Moreover, some of the pieces, such as the numerous drawings and watercolours of Paris that were acquired as documentary records of lost locations rather than for artistic importance, were harder to gauge in value.

Most of those estimates were left far behind come sale day as a huge crowd filled the room at the Hôtel Drouot auction centre and the 190 lots were all sold for a hammer total of €259,170 (£221,513).

The traditional international demand emerged. “There were lots of Americans who came specifically for this sale,” said Lucien, as well as other nationalities including British and Australians.

But this time, he added, the majority of the buyers, 80%, were Parisian, testimony to that increased demand from the home market mentioned above.

Included among the French clientele were a number of chefs.

This 18 x 15in (46 x38cm) oil on canvas of 1896 signed and dated by Emile Désiré Liénard depicts the Rue des Gobelins showing the tannery district and is interesting for its depiction of the Bièvre, Paris’ second river which starts near Guyancourt and flows into the Seine.

Being used in the past by the tanneries and the dyers of the Gobelins tapestry works, this water source became polluted. Haussman’s urbanisation of Paris and sanitation work began the enclosure of the river and by 1912 it had been completely culverted. The painting sold for €700 (£598).

“From sale to sale Parisians have become more of a presence – now they come en masse

The most expensive prices came from the 60-odd examples of early shop signs. The first shop signs appeared in Paris in the 14th century and by the beginning of the 19th century you could find more than 1000 around the city.

But by the early 20th century the number had dwindled to around 200, hence the cultural importance of the efforts made by enlightened collectors such as Debuisson who spent the 1960s-70s saving as many as possible, often buying from shop owners when the business closed or the building was demolished or modernised with neon signage.

Recognition of the importance of her task came at the sale in the form of the acquisition of eight signs by the Musée Carnavalet, the Paris museum in the Marais district dedicated to the history of the French capital which already has a substantial collection of shop signs.

The museum secured them by its right of pre-emption which allows a French institution to step in and claim the lot for the price determined by the fall of the hammer.

Among the eight signs secured by the Carnavalet were a pair of gilt-iron models of snails at €10,200 (£8715); an intricate Art Nouveau sign from a lantern maker at €2500 (£2135); another for a wine merchant and cafe A l’Auverngnat de Paris for €900 (£770); a giant gilt-iron glove at €4500 (£3845) and a red painted sign composed of two open umbrellas for €1100 (£940).

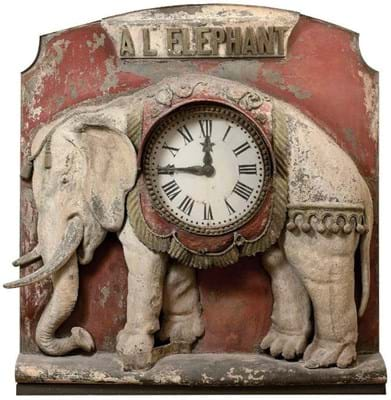

The most expensive sign in the sale, and the top lot of the auction, was a massive 5ft 11in x 6ft 1in (1.8 x 1.85m) zinc and painted tôle model of an elephant centred by a clock face surmounted by the inscription A L’ELEPHANT. This cost its purchaser, an American buyer, a multi-estimate €31,000 (£26,495).

Dating from c.1840, it came from the Maison Bresson founded in 1824 as a manufacturer of equipment for cafes and bistros such as counters and beer pumps.This was one of two elephant signs that originally stood at the premises on the rue de Lyon in the 12th arrondissement. The other, featuring a barometer, was destroyed in the 1960s before Debuisson acquired its companion from the last proprietors in 1969.

Another high-priced lot was an ensemble of verre eglomisé panels that decorated the outside of the Boulangerie Patisserie Des Statues on the rue de la Tombe Issoire in the 16th arrondissement. This realised €22,000 (£18,800).

Debuisson also collected a range of street signs ranging from the early stone plaques with engraved lettering from Louis XVs reign through to the familiar blue and white enamel signs that are still so much part of the Paris street scene.

Street lamps, and furniture and elements of the Paris Nord-Sud Metro made up much of the rest of the sale.

£1 = €1.17