In February 1603, the Portuguese merchant ship Santa Catarina, was seized by the newly-formed Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Ostindische Compagnie or VOC) off the coast of Singapore.

Her rich cargo, including as many as 100,000 pieces of the Ming blue and white hitherto known as Kraakporselein, proved a sensation when sold at auction in Middleburg and Amsterdam.

Agents for James I of England and Henry IV of France were among the successful bidders. At a stroke, a pan-European market for porcelain as an expensive but readily obtainable luxury item was born.

All objects tell stories about commerce, taste and the societies for which they were made, but few are as voluble as those made for export from the lands once collectively called ‘the Indies’.

Works of art made in 17th and 18th century China, Japan, India, Sri Lanka, Indonesia and the Philippines for a Western audience speak of exploration, colonisation, the exchange of ideas and, above all, the sense of wonder and excitement that once accompanied the exotic.

Chinese porcelain – ‘white gold’ from the kilns of Jingdezhen in northeastern Jiangxi province – was among the first global commodities and at the very core of the Indian Ocean luxury trade.

Porcelain had reached Europe by the (the earliest documented piece here by 1381). It had arrived in Central Asia and the Middle East much earlier, the contact with the Muslim world key to driving the development of ceramics in the Yuan and early Ming periods.

However, kraak wares – named after the Portuguese supercargos or carracks that transported it in payloads of up to 800 tons – were the first porcelains to arrive in Europe in any quantity. Kraak was also among the earliest East-West artistic hybrids, crafted with the same materials and technical virtuosity as pots made for the domestic market but in forms new to the Chinese repertoire and in decors designed to fire the foreign imagination.

Specialist export porcelain dealer Michael Cohen of Cohen & Cohen describes them as “some of the first fusion works of art”.

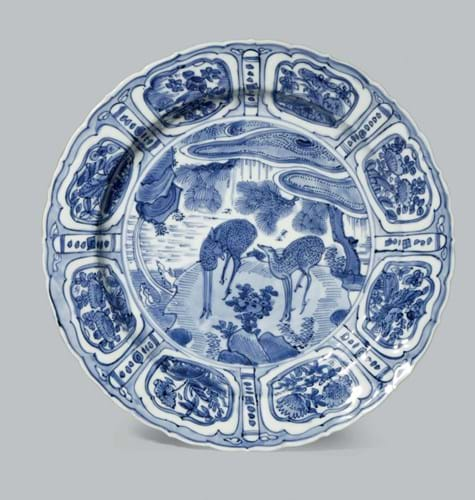

This 8in (21cm) ex-Bluett & Sons dish, sold for £14,000 (plus 25% premium) at Woolley & Wallis in Salisbury on May 23. It is among fewer than 50 high quality Wanli (1573-1620) kraak wares known to carry an egret mark.

In a famous letter, part culture diary, part industrial espionage, penned from Jingdezhen in 1712, the French Jesuit priest François Xavier d’Entrecolles explained the production process and some of the occasional teething problems.

“The porcelain that is sent to Europe is made after new models that are often eccentric and difficult to reproduce; for the least defect they are refused by the merchants, and so they remain in the hands of the potters, who cannot sell them to the Chinese, for they do not like such pieces”.

Some of this remains true in the marketplace today.

While Chinese ‘private trade’ and ‘country house’ porcelain has scarcely waned in popularity in Europe and the US since the Stuart era, predictions that it might soon find favour amongst the new wave of Chinese collectors have largely proved premature. For now at least, the market remains in the West.

It is priced accordingly. Porcelains of the type that comprised the famous Nanking or Diana cargo sales dispersed by Christie’s in Amsterdam in the 1980s and ‘90s can be bought for two- and modest three-figure sums.

“For now at least the market for most export wares remains primarily in the West”

Much higher numbers are paid for the more deluxe one or two per cent of export production that was specially commissioned by the aristocratic and merchant classes at prices tenfold or more those of standard blue and white ‘landscape’ wares.

The development of the famille rose palette by Jesuit missionaries working in the imperial workshops in the 1720s was key – something referenced half a century later by Josiah Wedgwood as he congratulated himself on the success of his creamware in India.

“Queen’s Ware”, he wrote to a friend in 1767, “was already in use there, & in much higher estimation than the finest porcelain [sic]… Don’t you think we shall have some Chinese missionaries come here soon to learn the art of making cream colour?”

Coloured enamels changed not just the character of Qing porcelain but also the pace of production. Painting in underglaze blue necessitated the arduous 400-mile inland trip to Jingdezhen, meaning a lapse of two years or more between commission and delivery. Porcelain enamelled in workshops at the principal trading centre of Canton could be turned around in a matter of months or even weeks.

Some 3000 armorial dinner services were made for British customers before trade petered out in the late 18th century. And alongside family crests, country pursuits and classical mythology there could be topicality: the victory at Culloden, the trial of the libertarian John Wilkes or indeed the storming of the house of the chief bailiff of Rotterdam on October 4, I690 – the earliest known example of a topical subject on export porcelain.

Christie’s regular January sales of export porcelain, held in New York alongside the ‘parallel’ collecting area of Americana, typically include some good examples. Leading the sale in 2016 at $60,000 (plus 25% premium) was a punchbowl decorated en grisaille with the London Hospital, a building in Whitechapel begun in 1752 intended to serve the sick and injured poor of the East End.

The equivalent sale earlier this year included two of a well-known series of doucai plates enamelled with figures from the commedia del’arte and satirical comment on the 1720 South Sea Bubble ($10,000) and a child’s coffee pot from a service apparently ordered on the occasion of Charles IV’s accession to the Spanish throne in 1788 ($5500). The decoration here copies a medal struck to celebrate the occasion by the Royal University of Mexico.

“The Mediterranean offered the Bible and matchlock rifles. In return came silk, silver bullion and lacquerwork”

East meets West

The key characteristics of Chinese export porcelain – an Eastern product with a Western-friendly flavour – are common to most export wares whether made in Canton, in Kyoto’s lacquer workshops or in the trading hubs of Goa and Vizagapatam.

Kensington Church Street dealer Amir Mohtashemi, who has specialised in this field for over 20 years, treats the subject as a whole: “My experience has shown that collectors initially focus on one particular area, but ultimately consider different types of trade pieces. Only then, by covering a larger spectrum of items, are they able to tell a more comprehensive story of the extensive trade that took place.”

He describes export wares as the ultimate story tellers. “Their appeal lies in the fact that the inspiration for their form and decoration stems from very different cultures – a fusion that resulted from trade corridors established over thousands of years.”

Owning such objects spoke not just of wealth and luxury but also of sophistication and an awareness of a world beyond close dominions.

A late 17th or early 18th century Indo-Portuguese tortoiseshell, ivory, wood and glass workbox with flower diorama, 14in (36cm) wide, from Amir Mohtashemi of Kensington Church Street, London.

Nanban (‘southern barbarian’) art emerged during the so-called ‘Christian century’ initiated by the arrival in Japan in 1549 of Francis Xavier (1506-52), a founder of the Society of Jesus.

Ships from the Mediterranean offered the Bible and matchlock rifles. In return came silk, silver bullion and the lacquerwork that could sell for ten-fold in European markets. What is believed to be the first auction of Japanese works of art in London was held on December 20, 1614 following the return from the Land of the Rising Sun of TheClove, a ship of the English East India Company. The sale was conducted by burning candle – the end of the auction signalled by the expiration of the flame.

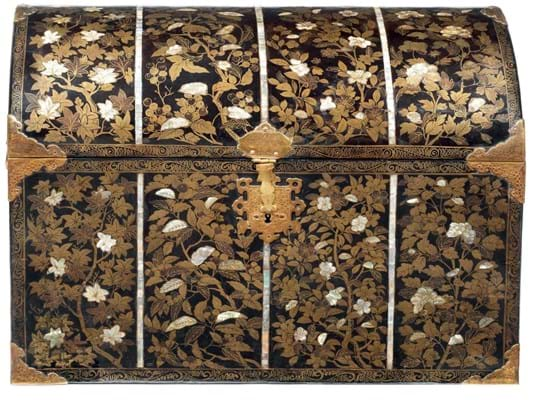

Nanban chests and cabinets decorated in gold hiramaki-e lacquer and mother-of-pearl offered the courts of Europe a glimpse of the splendours of the Momoyama age. That these pieces differed in form from those made for Japan’s domestic market is apparent in the lack of appropriate terminology:

rectangular coffers with domed lids were famously described as kanabokogata or boxes in fish-sausage shape’.

The closing of Japan’s borders during the Tokugawa period only served to add to a sense of mystery that continues among European collectors today. Lisbon, London and Paris are the places to find nanban wares for sale.

“It is difficult to generalise, but it is fair to say that the majority of demand is from the recipient country where these objects were destined for,” says Mohtashemi.

The subcontinent

The Portuguese, first to establish regular trade with China (in 1513), and the first to make landfall in Japan in 1542 had also been the first in India and Ceylon (modern-day Sri Lanka) in 1498 and 1505 respectively.

In India, Portugal’s merchants had found the means to monopolise the spice trade but relatively little in the way of luxury furniture: even the finest dining and socialising conducted while sitting on exquisitely woven carpets or dhurries.

An exception were the giltwood low chairs encountered in the Bay of Bengal that were adapted to include the motifs of the high Renaissance.

They only very occasionally appear for sale although a late 16th century chair of this type was sold by Bonhams in Chester in 2012 for £13,500 (plus 25% premium) and a pair emerged at Bonhams on September 18 to sell at £15,000.

It was more typical that early Portuguese settlers – and later the Dutch, the French and then the British – imported furniture to India where the designs were copied and interpreted by local craftsmen.

Indo-Portuguese or Anglo-Indian furniture follows European shapes and methods of construction but received its twist of exotica courtesy of materials (tropical hardwoods, turtle shell, mother-of-pearl and ivory) and the carved or inlaid flourishes that were distinctly sub continental.

“The first sale of Japanese works of art in London was held in 1614 following the return of The Clove”

Centres of production emerged in Gujarat, where the focus was upon lustrous articles fashioned from mother-of-pearl, and in Vizagapatam on the Coromandel Coast where the making of ivory furniture and boxes flourished in the latter half of the 18th century.

Goa in particular grew from a remote province to become the eastern trading capital of the Portuguese empire and the seat of Christian imperialism, its local religious and secular art an exemplary blend of southern European and Indian aesthetic sensibilities.

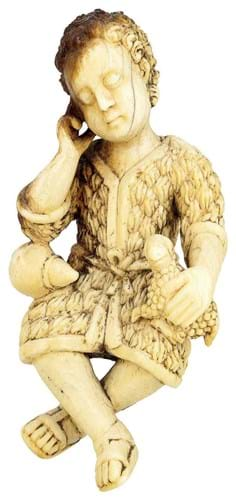

An 18th century Goan ivory carving of Christ as the Good Shepherd sold by Matthew Barton of London on June 6 for £800 (plus 24% premium). Indian-made Christian ivories made their way to Spain and Portugal or were sent to dominions such as Mexico and the Philippines while others entered aristocratic collections as curios and collector’s pieces. Demand for Goan ivories has weakened since the UK debate on the ivory trade started some three years ago.

Some of these distinctive wares are now finding favour with buyers from the subcontinent who, in the past decade, have demonstrated a growing interest in this field. Prices for Indo-Portuguese inlaid table cabinets and Gujarat mother-of-pearl have responded although Mohtashemi believes there is still room for growth.

“Despite the demand and rising prices for Indian export ware, there are still many opportunities to acquire high quality and historically significant objects for modest prices compared to Chinese works of art,” he says.

Perhaps this will be the next chapter in the long market history of export wares – integral to the story of any nation state and the story of globalisation itself.

An artist trained in the Chinese tradition carefully copying a European print can create a sense of incongruity. This rare Yongzheng blue and white dish, 18in (45cm) diameter, is painted to the centre with Christ as a young man with John the Baptist within a border of landscape reserves, cherubs amidst fruit and flowers and the inscription Mat 3.16. It sold for £26,000 (plus 22% buyer’s premium) at Woolley & Wallis in Salisbury in 2013. A slightly larger dish from the celebrated Mottahedeh Collection, dated to c.1725 is pictured in China for the West by David Howard and John Ayers where it is noted that ‘it is possible that this ware was first designed for use by missionaries in China and Japan, and only incidentally exported to Europe as a curiosity’.