Making money in the auction business is seldom quite as easy as it sounds. Closures can happen occasionally, with vendors left to pick up the pieces.

Australia provided a spectacular recent example when in December 2017, one of its largest fine art auction houses, Mossgreen, went into administration with debts of Aus$12m (£7m) and many vendors among the 400-plus creditors.

A hive of activity followed a grim situation. Vendors successfully challenged the efforts of the receivers to charge big for the receipt of unsold goods, the Auctioneers and Valuers Association of Australia (AVAA) called for all auctioneers to introduce client accounts (known here as trust accounts), and three new auction houses set up in Melbourne as ex-Mossgreen staff chose to go it alone.

Abacus Auctions (coins and stamps), Donington Auctions (classic cars and automobilia) and Gibson’s (art, antiques and jewellery) all promise to conduct business according to the AVAA’s recommendations.

But while the long Mossgreen legal process continues, 10 months on the dust has started to settle on the auction scene Down Under. And, by and large, it has been a decent year for the Australian market.

Market obstacles

In truth, the art market in Australia is familiar with bumps in the road – and not just those associated with global economics or the ebbs and flows of the Australian ‘resources boom’.

A Resale Royalty Right charged at a flat rate of 5% on art sold for more than Aus$1000 came into effect in 2010. Tougher copyright rules regarding reproduction rights followed, while the 2011 changes surrounding Self-Managed Superannuation Funds led to a big sell-off of modern and contemporary art that had been bought for investment purposes alone. The result was saturation, falling prices, scandal around fakes and a beleaguered dealing community.

That fall-out is still being felt. Damian Hackett of South Yarra, Melbourne, and Paddington, Sydney, firm Deutscher and Hackett says: “The primary challenge now is attracting more participants – more collectors and more dealers too. Restrictive copyright laws and the introduction of an uncapped resale royalty has meant the number of old-guard art dealers is now dwindling.”

Nonetheless, the cream did rise to the top. “The volume of works fell and certainly the number of people participating in the market also fell, but great works held their own or grew in desirability and value.”

Hackett describes 2017 as “an excellent year with the market as a whole, and Deutscher and Hackett’s share of it, growing well”.

According to numbers crunched by the Australian Art Sales Digest, the total annual turnover of fine art at auction in Australia grew from Aus$105.7m (£56.9m) in 2016 (a level at which it had languished since 2007) to Aus$141.6m (£76.2m). Deutscher and Hackett’s take grew from 18% to 26% with $37m (£20m) – pretty much the same number posted by fellow market leader Sotheby’s Australia.

John Keats, senior executive officer at Sotheby’s (a name used under a licence agreement), tells ATG: “the market is becoming more knowledgeable and demanding for quality, which is always a challenge to satisfy”. However, indicative of the strength observed since 2017 has been the renewed vigour for art by mid-20th century heavyweights such as Charles Blackman (1928- 2018). The buyer of Blackman’s Mad Hatter’s Tea Party (1956) for $600,000 in May 2009 resold it for a record Aus$1.55m at Sotheby’s last November.

This year, with sales such as Russell Crowe’s Art of Divorce dispersal, Keats says Sotheby’s has “sold almost twice as much Australian art in value as our closest competitor” and has “over 50% of the Australian auction market” for jewellery.

John Albrecht, managing director at Leonard Joel (South Yarra, Melbourne, and Woollahra, Sydney) where sales last year were around Aus$30m, believes the market is now benefiting from what, in hindsight, was a serious correction.

“The bubble-like dynamics have been resolved,” he says. “The best example of this is in prices for Aboriginal art, where the secondary market for this important genre now represents fair and sustainable market value.

"Similarly, but less dramatically, traditional pre-modern Australian art has stabilised, modern Australian art market is robust and, while there is an increased appetite for contemporary art, the effect on the secondary market is more gradual.”

Diversification

Previously there was a sense that the health of the Australian art market as a whole depended on Australian pictures alone. This is now evolving.

“A challenging auction market changed the nature of auctions. The number of international works of art [we] sold grew and results for artists such as Bridget Riley, Barbara Hepworth, Lucian Freud and many others not only assisted our turnover, but also attracted international collectors to our sales,” says Hackett.

The firm’s November 28 auction includes a work on paper by Leon Kossoff (estimate Aus$45,000-65,000) and the Andy Warhol screen print Rebel Without a Cause (James Dean) (estimate Aus$100,000-140,000). It’s no longer the case that Australia is simply too far away from the global art scene to make an impression.

Changing tastes

At Leonard Joel, Albrecht references what he terms “a profound change in taste and collecting habits that has occurred in line with shrinking domestic spaces and interiors with more glass than wall.”

Australians who once marvelled at buildings and objects more than a century old will now, too often, relegate pre-war furnishings to the status of ‘those pieces that my parents or grandparents owned’.

Newer collector categories such as modern design, prints and photography and pre-owned luxury are now priorities for Albrecht as the firm approaches its centenary in 2019 – so too the sort of mixed-discipline single-owner consignments that they are picking up in the wake of the Mossgreen debacle.

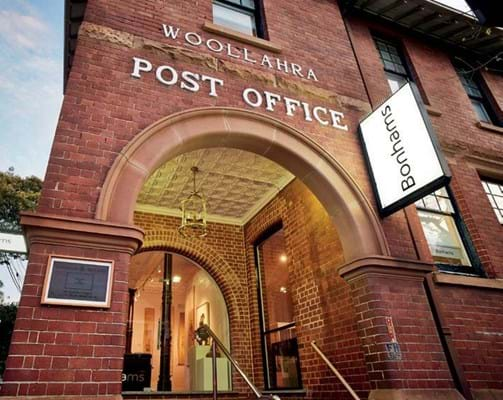

Business in New South Wales has grown significantly since the ‘watershed’ sale of the estate of publisher and philanthropist James Fairfax, prompting Leonard Joel to move into a larger space on Queen Street, Woollahra.

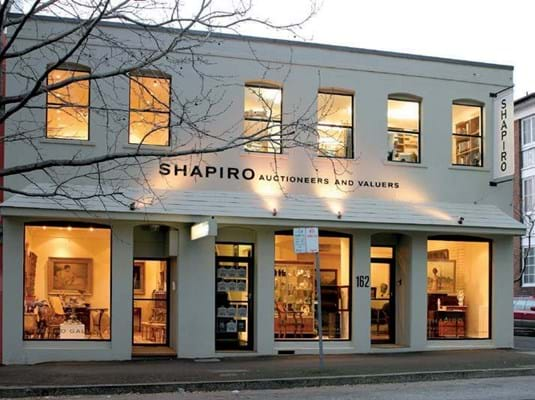

Shapiro, a fixture on Queen Street for more than 20 years, has also experienced a strong flow of goods since the demise of a near-neighbour.

Luxury design

“Scarcity of good stock is always a problem in our industry, particularly when you live in a country with a relatively small population [24m]. However, we have established ourselves in 20th and 21st century design while luxury design was established about four years ago and is one of our fastest-growing departments,” says managing director Andrew Shapiro.

Has the issue of trust accounts become more important to consignors? It is certainly a question vendors are now asking.

“The dire situation many Mossgreen vendors found themselves in prompted an evaluation on our part,” says Albrecht. “While we have a long-established practice of a diligently managed client account, entirely separate from our trading account, we thoroughly audited our processes and introduced a new rapid settlement service that guarantees a seven-day settlement for all collections of $250,000 and above in value.”

The March edition of the firm’s monthly house magazine included an article on the topic titled The Importance of Trust. “As the CEO of Australia’s largest auction market, it is my duty to reassure prospective clients that recent events are the exception rather than the norm,” adds Albrecht.