Halfway between a photo album and a printed book lies the photobook.

In the age of Instagram, when almost a million images are shared across social media every minute, leafing contemplatively through a photobook allows for a deeper appreciation of the interaction of image and text. Yet this is a relatively young collecting field.

Whereas early photography itself began to receive serious curatorial and collecting attention in the 1950s and ‘60s, photobooks – published in multiple identical copies with an imprint and letterpress text – had to wait until the 1980s to come under the microscope of academics such as Helmut Gernsheim, Lucien Goldschmidt and Weston J Naef.

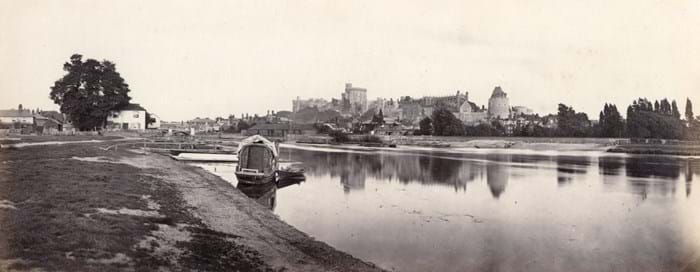

Using the darkroom equipped punt that can be seen in the foreground of the view of Windsor reproduced here, Victor Prout spent five years photographing views along 'The Thames from London to Oxford'. Forty panoramas, mounted on card with printed captions, make up a rare complete example of the 1862 first edition of that work which sold for £13,000 at Bonhams on March 1.

Thirty years on and discoveries are still being made, scholarly work is still being done and it remains a fruitful area for collectors to forage.

The term ‘photobook’ is a wide-ranging one: the photo historians Martin Parr and Gerry Badger describe it as “a book – with or without text – where the work’s primary message is carried in photographs”.

The Victorian era

However, the focus here is on books which have original photographs pasted in – a format which began in the 1840s and had largely tailed off by the last quarter of the 19th century.

In fact, the photographic print, the photo album and the photobook were triplets, emerging into the world at the same moment.

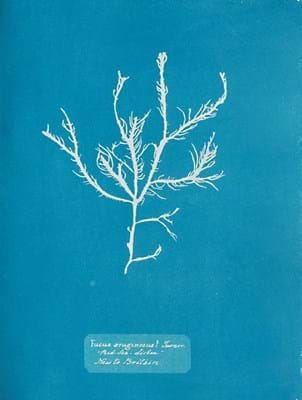

The paper negative was key. Although Louis Daguerre’s silvered copper plate produced a rich, highly detailed image, each daguerreotype was a one-off, and lent itself to display only in a frame, case, or locket. With a paper negative, on the other hand, William Henry Fox Talbot’s rival calotype allowed for an almost infinite number of identical positive prints. These could also be pasted into a codex – just as one might mount watercolours, engravings, or pressed flowers in a scrap album.

“The Great Exhibition was the photobook’s coming out party”

Fox Talbot created the first photobook when, unveiling his calotypes to the public, he mounted them in the first part of The Pencil of Nature, issued on June 29, 1844, to 274 buyers. Complete copies of this pioneering periodical are rarer than the Gutenberg Bible.

Slightly more obtainable is his 1845 Sun Pictures in Scotland, a copy of which is with Sims Reed at £65,000. However, in an attempt to make his invention known to a wider audience, in June 1846 Fox Talbot inserted a photo in each of the 7000 copies of the Art-Union journal. It was, as the editors wrote, “a great boon to our readers, many of whom, although they have heard much of the wonderful process, have not been yet enabled to examine an actual specimen.”

The magazine’s large circulation, and the unfortunate tendency of the prints to fade, means that examples can be had at auction for as little as £200 or £300.

Fox Talbot’s restrictive patent on the calotype meant that photography in England was slow to get off the ground. However, the 1851 Great Exhibition was, in some ways, the medium’s coming-out party. Not only was there the world’s first open photographic exhibition – 700 images were displayed – but the Crystal Palace was itself fabulously photogenic.

The JP Getty Museum in California holds an imperial-plate daguerreotype of a fully-grown tree that thrived inside the iron and glass structure.

The Great Exhibition spawned two major photographically illustrated books: Philip Henry Delamotte’s very rare Photographic Views of the Progress of the Crystal Palace of 1855 and the Reports by the Juries with its 154 calotypes. Bonhams holds a record for the latter, selling a presentation copy bestowed to Fox Talbot’s daughter at £180,000 in 2011, but copies typically sell in low- to mid-five figures.

Exotic climes

The focus of early photobooks was on British photography. But very soon more exotic climes were in the frame. Maxime Du Camp published his Egypte, Nubie, Palestine et Syrie album in 1851, while Francis Frith’s works on the same region began to appear in 1858.

With these topographical works, size matters: Frith’s Egypt, Sinai, and Jerusalem: a Series of Twenty Photographic Views, is “the largest book with the biggest, unenlarged prints ever published”, according to Helmut Gernsheim. It is now a six-figure work at auction, but a volume of a smaller-format Middle East photobook by him can be had for around £5000.

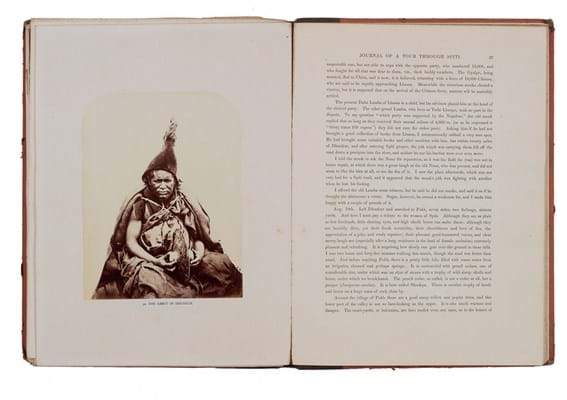

Linnaeus Tripe published works on Burma and Madras in the late 1850s, and an unexpected recent find at the bottom of the very last bookcase in a library in Scotland was a copy of Philip Egerton’s Journal of a Tour through Spiti, to the Frontier of Chinese Tibet (1864). At £15,000, it was worth as much as the rest of the collection put together.

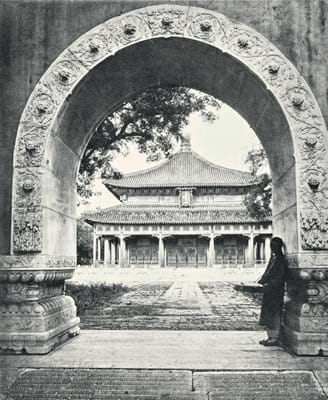

John Thomson set off for Asia in 1862 and spent a decade in the Far East. This summer, mammoth-format prints, newly produced from the original negatives, are being shown in London at the Brunei Gallery, SOAS (April 12 to June 22).

Thomson’s 1873 publication Foochow and the River Min is illustrated with 80 mounted carbon prints, while his Illustrations of China and its People, appearing the same year, makes use of another new technology, the collotype. Both works have risen rapidly in value in recent years thanks to their appeal to the Chinese market.

“A volume of photographs can explode into life at any time”

Brighton photo dealer Roland Belgrave sees strong demand for both Chinese and Indian photobooks, especially those “that have an interesting ethnographic angle and strong images”. This global appeal makes sense: the language of photography is universal. As Martin Parr says: “A volume of photographs, even one from the distant past, can explode into life at any time, when stumbled upon by a sympathetic reader.”

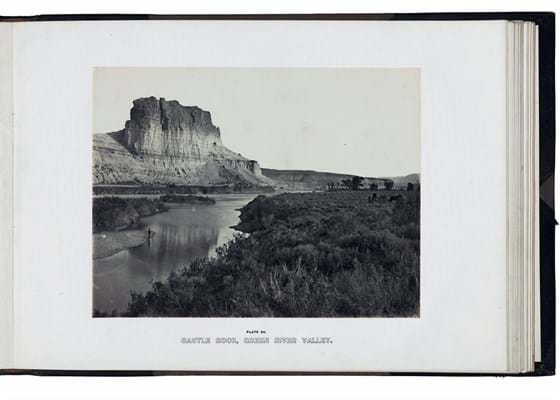

Other 19th century photobooks cover the American Civil War, Yosemite, the Arctic, and even the Moon – all big-ticket items. But the deluge of photobooks published in Britain from the 1860s – and a currently weak market for British topography and Victoriana in particular – mean that the entry-point for collectors can be much lower. There are collectable photobooks at all price points.

On a practical note, photographs mounted in a book that is shelved in a library are often better preserved than their framed brethren under constant exposure to daylight. Also, unlike photo albums, there is no VAT on printed books illustrated with photographs.

At ABA dealer Patrick Pollak, the Exeter-published Devonshire Celebrities is £100, Howitt’s Ruined Abbeys and Castles £160, and Memorials of the Hospital of St Cross at Winchester is £175. The more exotic Swiss mountaineering title Oberland and its Glaciers: Explored and Illustrated with Ice-axe and Camera can be had elsewhere from £500.

By the turn of the 20th century, technologies such as photogravure and halftone printing made mounting original photographs in books outmoded. Perhaps because the formats are aesthetically so different, few private collectors combine early and modern photobooks in their libraries.

Lindsey Stewart of dealer Bernard Quaritch detects “very little overlap” here, noting that by contrast “in academic libraries there can be a real appreciation of the history of the book as a format for extending the reach and depth of a photographer’s vision”.

She believes that a more all-encompassing approach by those collectors who focus on a theme, rather than an historical period, could bring richness to their collections.

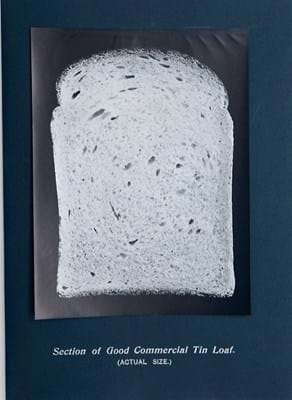

For those who insist on real photographs in their books, however, the last hurrah of the genre came in 1903. Owen Simmons’ entirely serious Book of Bread had two mounted silver gelatin prints… of slices of bread. With a copy available from Peter Harrington at £1500, a hesitating buyer would be wise to use his loaf, rise to the occasion and toast the beginning of a photobook collection.

Matthew Haley is head of books, maps, manuscripts and historical photographs at Bonhams. Despite a predilection for albumen, he dabbles in digital photographs on Instagram under the username matthewjohnhaley.