Delving into the rich seams of London’s cartographic history is akin to an archaeological dig.

These are eyewitness documents showing the bull and bear baiting pits which predated Shakespeare’s Globe, Old London Bridge with its shops, pubs and houses, the wharves and docks which crept east as the Thames became the busiest port in the world, the great railway termini and public parks of the 19th century or the airports and football grounds of the 20th. Depending on one’s literary bent, these are the streets trodden by Samuel Pepys or Samuel Johnson, Charles Dickens or Virginia Woolf.

For the modern-day Londoner, old maps are both reassuringly familiar and disturbingly different. Across 450 years of printed map-making – the years during which London grew into a major world city – there is no era in which the capital ossified. Old landmarks were torn down and new ones took their place. It is a rich field for the collector and a popular one too: demand comes from the millions who live or work in London, or visit each year.

Lagging well behind other commercial and political centres, London was mapped 80 years after the first printed atlases. The best available map of pre-Reformation London was not published until 1855 – compiled by the antiquary William Newton (a copy is available from Altea Gallery at £1500).

William Newton’s 'London, Westminster and Southwark as in the olden times', showing pre-Reformation London in the reign of Henry VIII, compiled from maps, documents and surviving structures and published in 1855. Priced at £1500 from Altea Gallery.

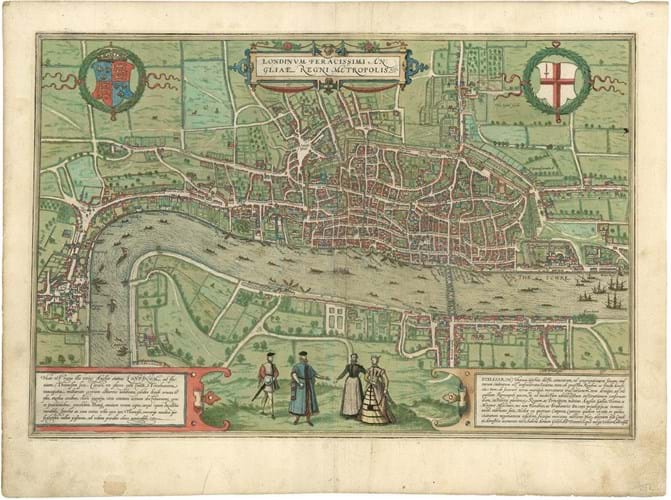

The first printed maps of the capital were German. Not a single copy exists of the oldest, a bird’s-eye map commissioned by German merchants of the Hanseatic League seeking favour with Queen Mary in the 1550s. Instead the first surviving printed map is one created in Cologne by Georg Braun and Frans Hogenberg in 1572 as part of their great city atlas, the Civitates Orbis Terrarum.

Copies do appear on the market: an example with modern hand colour is currently available for £6500 (Garwood and Voigt) and one with original hand colour £9500 (Daniel Crouch Rare Books). There are a number of early derivatives which are more affordable. The woodcut version which appeared in editions of Sebastian Munster’s Cosmographia from 1598 onwards can often be found in the £1000-£1500 bracket.

1666 and all that

Seventeenth century London was buffeted by civil war, plague and fire.

“17th century London was buffeted by war, plague and fire”

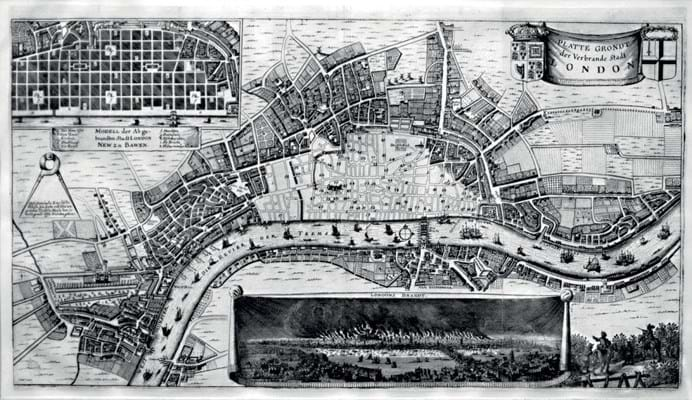

The Great Fire was international news, and a 1666 Frankfurt printing of Platte Grondt Der Verbrande Stadt London, a contemporary map showing the extent of the destruction, is currently offered at £4000 (Jonathan Potter).

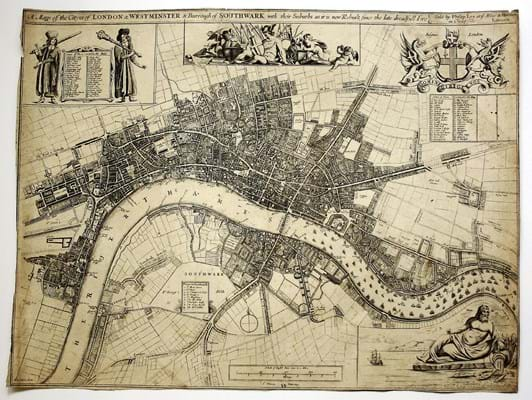

Rarity sometimes means that allowances can be made for condition.

An example of John Oliver’s 1676 Mapp of the Cityes of London & Westminster, showing the early phases of the rebuilding of London after the fire, is offered at £7500 despite suffering some loss (Clive A Burden). It is one of three recorded examples of a map compiled by one of the pair of City Surveyors who oversaw the reconstruction work, with further input from Christopher Wren and Robert Hooke.

A popular genre fed by a growing customer base in the 18th century was the ward plan, chiefly used to illustrate new editions of John Stow’s History of London, or William Maitland’s The history and survey of London: from its foundation to the present time.

Ward plans

Wards were an important tier in local government, and the maps engraved for Maitland are decorated with the arms of aldermen. Individual ward plans can mostly be bought for £100-250, depending on area. An example of the complete 1754-55 sixth and best edition of Stow, handsomely rebound in diced russia c.1800, is currently offered at £7500 (Angelika Friebe).

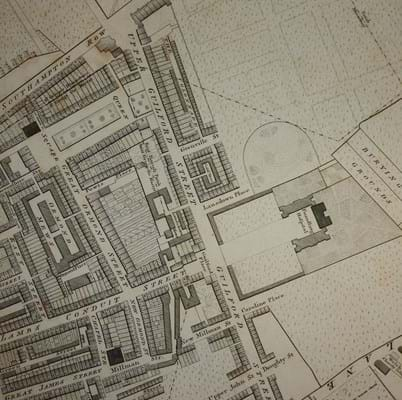

These maps only deal in detail with the built-up area in the 18th century, when London was relatively compact. To trace the development of once small villages which are now firmly inside central London, such as Chelsea or Hampstead, one must turn to maps which cover the environs. John Rocque’s 1745 London… near ten miles round is one of the most important of these; Rocque is credited with revitalising large-scale mapping in mid-18th century Britain.

A complete example, measuring some 6½ x 10ft (2 x 3m), is currently on sale for £16,000 (Daniel Crouch). Richard Horwood’s 32-sheet map of the city (1793-99) is another milestone. At approximately 13 x 6½ft (4 x 2m), it was the largest map published in Britain up to that point as well as the first map to show London house numbers. Given its importance it can be surprisingly attainable: an example reached £3750 at Bonhams in November.

By the late 18th century, folding pocket maps had became popular. Frequently describing themselves as ‘new’ or ‘showing the latest improvements’, these were bread and butter for the commercial mapsellers such as Edward Mogg, George Cruchley and James Wyld who successfully campaigned to keep the Ordnance Survey out of central London for most of the 19th century.

James Fraser’s 'Panoramic Plan of London', 1837, an engraved map, dissected and mounted on linen, handcoloured in outline. Priced at £1250 from Daniel Crouch.

Survivors tend to be the most expensive and durable examples, which were hand-coloured, linen-backed and protected by slipcases. Some, such as James Fraser’s 1837 Panoramic Plan of London (Daniel Crouch, £1250), are extremely decorative and – rapidly rendered obsolete by London’s extraordinary growth – each map offers a snapshot of London history: the five-year period when Notting Hill was a racecourse, or when the old and new London bridges stood side by side.

Maps which were carried and used, rather than languishing on library shelves, have an immediacy to them as artefacts, but survival rates are correspondingly low.

Victorian London

The 19th century produced an explosion of official maps showing proposed docks, railways, parks, sewers, road improvement schemes and slum clearance projects. Not all reached fruition, and one could collect maps of a London that was never built.

“The Victorians pioneered statistical mapping”

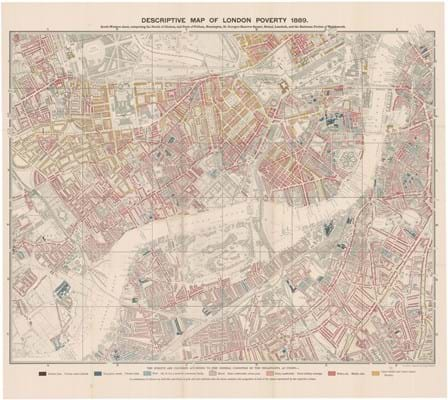

The Victorians also pioneered statistical mapping. Among the most famous is Charles Booth’s ‘poverty’ map, the large-scale socio-economic survey coloured to show degrees of wealth and social class. A full set of all three series of Life and Labour of the People in London, published 1889-1902, is currently offered for £16,000 (Altea Gallery).

John Snow’s spot map, recording an outbreak of cholera cases around the Broad Street pump in Soho, appeared in the second edition of On the Mode of Communication of Cholera, 1855. A founding moment in the history of epidemiology, it is extremely rare. An example reached £25,000 at Christie’s in 2012.

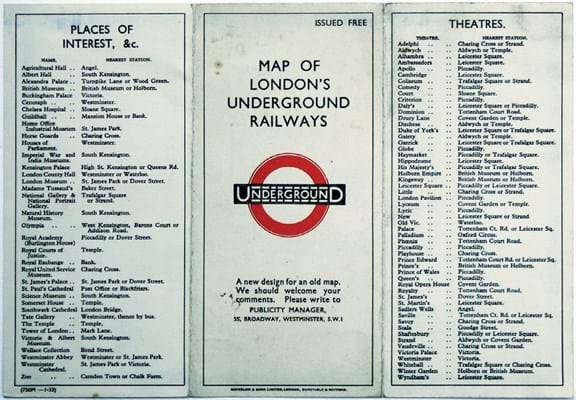

By the turn of the century advances in education and printing technology led to another growth in map production. More maps were printed in the 20th century than in any other, sold cheaply and – for the first time – often given away.

They were adapted to new forms of public and private transport such as trams, trolleybuses, the Underground and motor cars, and distributed by organisations ranging from local government to department stores.

Mass production ensures many survive in great numbers. Patrick Abercombie’s 1944 Greater London Plan can still be bought for under £100. With the odd exception – such as the edition of MacDonald Gill’s ‘Wonderground’ map sold as a souvenir of the British Empire Exhibition in 1924 (£2500 Barron Maps) – maps of festivals, exhibitions and royal events were frequently treasured as souvenirs and even in fine condition fall into the ‘cheap and cheerful’ bracket.

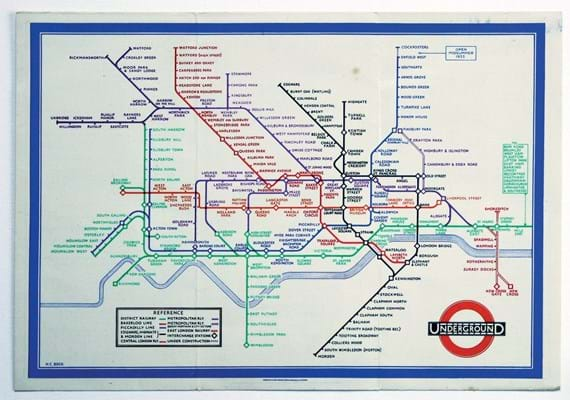

But not all well-known pre-and post-war maps are common. One would have needed second sight to guess that the first edition of Harry Beck’s London Underground diagram, given away at stations in January 1933, would come to be regarded as one of the most original maps of the 20th century. A good copy will retail for £2500 (Bryars & Bryars), while many pre-Beck Underground maps sell in the low to mid hundreds.

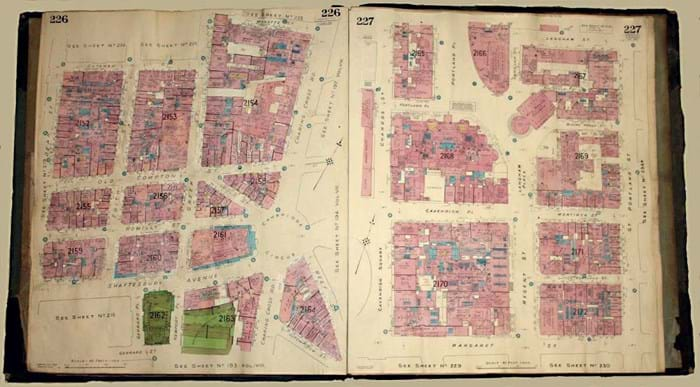

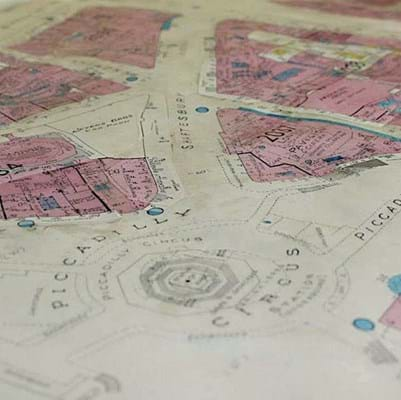

Among the best large-scale maps of this era are the fire insurance plans produced by the firm Charles E Goad, detailing building construction and use for risk assessment.

Rather than reissuing the maps every year, any changes were shown by pasting small printed tabs over what had gone before, until the sheet was so buried under layers of London history that it was necessary to discard it. A Goad atlas of 30 maps showing the West End currently retails for £3500 (Bryars & Bryars).

Some more recent maps are now attracting commercial interest.

As part of the Soviet global-mapping project in the 1980s, London was mapped in chilling detail by Russian cartographers – large-scale maps that contain a wealth of information which would have been superfluous to military requirements, but useful in the administration of the capital should ‘the revolution’ happen. A set of four sheets is likely to cost at least £500.

There are other specialist maps of a similar vintage which are showing signs of becoming equally rare, if not yet commercially valuable.

Consider the Gay to Z of London, published by the Man to Man bookshop in Notting Hill in 1977: the earliest separately published LGBT map of London and the sort of map – reflecting changing social attitudes – which is now in the collecting zeitgeist.

The best place to start exploring the mapping of London has to be the forthcoming London Map Fair (Royal Geographical Society, June 9-10).

“The Victorians pioneered statistical mapping”

Tim Bryars sells rare maps and books from Cecil Court, London WC2 and is a co-organiser of the London Map Fair. Visit bryarsandbryars.co.uk