Although nothing at all was in writing the claim was found by the High Court Judge to be enforceable. Court claims alleging binding oral agreements are not restricted to the art world. However, no written record does make life immeasurably more difficult.

A reading of the De Pury judgement provides a superb lesson on why it is worthwhile drawing up a comprehensive contract.

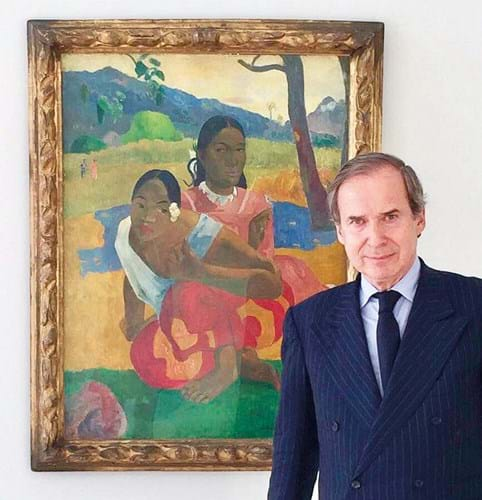

In this case the judge scrutinises with a microscope the discussions that take place between Simon De Pury and Ruedi Staechelin, the president of the family foundation that owned the Gauguin painting central to the dispute.

No one comes out of it smelling of roses – in the judge’s own words: “I did not find the evidence of Mr De Pury, Mrs De Pury or Mr Staechelin to be wholly reliable.”

The bottom line, however, is that after a rigorous 22 pages of analysis, he decides: “On 26 June 2014, Mr De Pury agreed with Mr Staechelin and Mr Paisner [another trustee] that if the painting was sold for $210m Mr De Pury would be paid a commission of $10m.”

A host of different circumstances and considerations have to be assessed by a judge to decide whether oral discussions amount to a binding contract in English law.

Sports Direct

Take another, recent, very high-profile case. In July 2017 Jeffrey Blue had his day(s) in the High Court against Mike Ashley of Sports Direct fame.

Blue, an investment banker, claimed that, at the Horse & Groom pub in Great Portland Street, Ashley had promised him £15m if he could get the share price for Sports Direct to double to £8 per share (which it did just over a year later).

Again the High Court judge trawled remorselessly through the evidence provided by the witnesses for both sides, before giving an excellent brief summary of what these sorts of cases, concerning alleged oral agreements, are about:

“Generally speaking, it is possible under English law to make a contract without any formality, simply by word of mouth.

“Of course, the absence of a written record may make the existence and terms of a contract harder to prove. Furthermore, because the value of a written record is understood by anyone with business experience, its absence may – depending on the circumstances – tend to suggest that no contract was in fact concluded. But those are matters of proof: they are not legal requirements.

“The basic requirements of a contract are that: (i) the parties have reached an agreement, which (ii) is intended to be legally binding, (iii) is supported by consideration, and (iv) is sufficiently certain and complete to be enforceable.”

In this case the judge looked at the context of the discussions, in the pub, when all parties been drinking, and concludes that the conversation had been jocular.

“No reasonable person present would have thought that the offer was intended to create a contract. They all thought it was a joke.

“The fact that Mr Blue has since convinced himself that the offer was a serious one, and that a legally binding agreement was made, shows only that the human capacity for wishful thinking knows few bounds.”

Mr Blue probably turned very blue when he heard these words.

Perhaps the difference was that De Pury and Staechelin never met in the Horse & Groom. In that case, the judge was very clear that there was indeed a legally binding deal for $10m.

So, if you are going to enter into an oral agreement for a substantial sum of money, make sure you do it at a fitting venue – preferably not the pub.