For several years, one narrative has been the accepted norm in the media: antiquities have probably been stolen and, if you buy them, somewhere along the line smugglers or terrorists have profited.

Against this onslaught of depressing coverage, crackdowns and a surge in repatriation, auction houses and dealers have had limited success in differentiating themselves from the illegitimate trade. “We have come to expect a new negative story every day,” one dealer told ATG.

However, the trade is now taking a more pragmatic approach. In early June, Sotheby’s announced it was taking Greece’s ministry of culture to court over the ownership of an ancient Greek bronze horse. The auction house said the highly unusual legal attempt was “to clarify the rights of legitimate owners” amid a surge in claims by countries of origin.

Then came the London sales and with it the bold inclusion of a clutch of lots at Sotheby’s and Christie’s that had passed through the hands of disgraced art dealer Robin Symes. Although never formally convicted of antiquities trafficking, Symes was exposed as a key player in a network that traded in looted archaeological treasures in the 1980s and ‘90s. Many lots associated with him have been tainted as a result.

Crucially, the three pieces offered earlier this month had clear provenance pre-dating Symes’ ownership. In the event, all three pieces sold well in excess of their guides.

Laetitia Delaloye, department head at Christie’s in London, said: “Symes handled thousands of objects. Not all were taken directly from source. It was important for us to find provenance pre-dating Symes. Had there been any doubt, however, it would have been a completely different story.”

Full transparency

The move was commended in the trade as an example of the market’s commitment to full transparency while also highlighting the nuanced arguments of ownership.

“Yes, Symes did have some problematic pieces, but by no means was everything he touched problematic,” said Francesca Hickin, head of antiquities as Bonhams. “The conversation around him, especially by those who are anti-trade, has been far too simplistic and purposefully naïve.”

Taken as a whole, the series followed recent trends. Blockbuster entries were in short supply, highlighting the scarcity of top-class material in this market. In all, more than 500 lots of jewellery, pottery, glass, sculpture and frescoes from across the ancient world were offered, totalling a solid if not spectacular £6.77m.

Egyptian pieces and classical marbles remain the market’s hottest areas, although watertight provenance continues to be crucial, and prices tend to increase the further back a piece’s history can be traced. Madeleine Perridge, director of the Kallos Gallery in Mayfair, said the auctions “showed the strength of the market for well-provenanced ancient art, particularly Greek vases, Classical sculpture and Egyptian art”.

Sotheby’s

After shelving London antiquities sales for a number of years, Sotheby’s returned to the fray in 2016, much to the delight of the London trade.

The 78-lot sale on July 3 sold 85% of lots and totalled a mid-estimate £4.49m, the firm’s best results since relaunching sales.

The catalogue provided the only seven-figure entry: an Egyptian limestone figure of a seated scribe from the Middle Kingdom.

For more than 100 years, the modestly sized 10½in (27cm) high cloaked figure had been part of the furnishings of the Palais Stoclet in Brussels, placed amid the frescoes and mosaics of Gustav Klimt. Passed by descent, it sold for a middle-estimate £1.25m.

Egyptian art was Sotheby’s strongest suit, producing the top three prices and a number of other eagerly contested lots. A fine wood mummy mask still bearing traces of original polychrome and glass inlay, and with a pre-1970 provenance to the English collector John Hewett, sold for £160,000 against a £100,000-150,000 guide.

Equally sought-after was a limestone round-topped stele, also retaining original polychrome and with a much-coveted 19th century provenance. It took £220,000 against a £120,000-180,000 guide.

A 1st century Roman marble funerary altar had been first recorded in the collection of the 15th century Tuscan banker Agostino Andrea Chigi. It resided in the grounds of Chigi’s grand villa in Rome at the same time Raphael was painting the interior.

Other former owners included the late British model Eva Rhodes (murdered in Hungary in 2008) and Symes. Guided at a tentative £45,000- 60,000, the 29 x 2ft 5in (73 x 54cm) piece was taken to £150,000.

Roman marble busts are popular, provided price, condition and provenance are well-pitched. A satisfying result for the Sotheby’s research team was provided by a 9½in (24cm) high portrait head of a man from the 2nd quarter to the 3rd quarter AD.

Since its last sale in 2012 (at Bonhams where it had made £28,000) an image of the bust (minus its nose and chin) had been found, placing it at Wilton House in Wiltshire in 1923. It had entered the collection there in the 17th century under Thomas Herbert, the 8th Earl of Pembroke. At Sotheby’s it sold on top estimate for £60,000.

Christie’s

The star performer at Christie’s £1.53m sale on July 3 (pictured above), turned out to be something of a flyer.

The 3ft 8in x 18½in (1.11m x 47cm) Roman marble relief fragment dated to the c.1st century AD soared to £180,000 against a £10,000-15,000 guide. Its dimension and architectural elements suggest it had once adorned a monumental altar or a public building, making it scarcer than the more common sarcophagus fragments.

Adding to this was its decorative appeal and an unbroken provenance dating back to c.1961-62. It was bought by a European private collector.

Leading a strong Egyptian field was a small 12in (30cm) bronze from the Late Period representing the goddesses Bast and Wadjet. Last offered at auction in 1987, it sold for more than twice its guide at £150,000 to a private buyer in the US.

Christie’s placed its most valuable antiquity in The Exceptional Sale on July 5 in King Street.

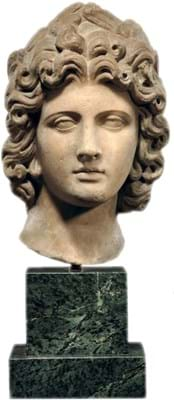

The impeccably well-preserved 13in (33cm) high Roman marble head of an androgynous-looking god from the 2nd century AD had been acquired at Sotheby’s in 1967 by Symes, before entering a Spanish private collection in c.1972 and remaining there since.

It sold to a private collector at £350,000, well over the £150,000- 250,000 guide.

Bonhams

Egyptian and classical antiquities made the biggest contributions to the £843,890 sale held in New Bond Street on July 5, with 64% of lots finding new buyers. Top honours went to a 2ft 4in (70cm) high Roman marble draped female figure (pictured above) dating from the c.1st century BC to 1st century AD.

Key to its success was evidence of old 19th century restoration work, indicating along and most likely Western provenance. Three phones and bids in the room and internet pushed bidding beyond the £15,000-20,000 guide to £82,000, where it was knocked down to dealer Martin Clist of Charles Ede.

Another financial highlight was a larger c.1st-2nd century AD Roman marble of Harpocrates which sold on bottom estimate at £40,000, to Ollivier Chenel of Galerie Chenel in Paris.

Some of the sale’s biggest bidding tussles came in the Egyptian section, with the most ‘accessible’ or typically Egyptian pieces proving most desirable.

Among them was a Late Period 22 x 13in (57 x 33cm) painted gesso wood sarcophagus prayer panel, richly decorated with hieroglyphs, canopic jars and the god Anubis administering to a mummy on a funerary bier. Last sold at auction in 1978 when it made £1500, it was secured by the trade at more than three times its top guide at £26,000.

By contrast, Middle Eastern art is a noticeably softer area, with the region’s on-going troubles the primary reason for its decline.

At Bonhams, a 47- lot collection provided many of the sale’s unsold lots, despite a stellar provenance. Among the casualties were two striking Piravend bronze idols from western Iran, formerly owned by the famous French painter André Derain.