The movement (now in a later case) is thought to be one of two marine timekeepers commissioned from the clockmaker Severijn Oosterwijck (c.1637-c.1694) by the Scottish nobleman Alexander Bruce (1629-81).

Dreweatts, which will offer the clock at its March 15 sale, is reluctant to estimate its value. However, specialist Leighton Gillibrand is of the view that the Bruce-Oosterwijck timepiece is the better of the two survivors and could thus bring a six-figure sum.

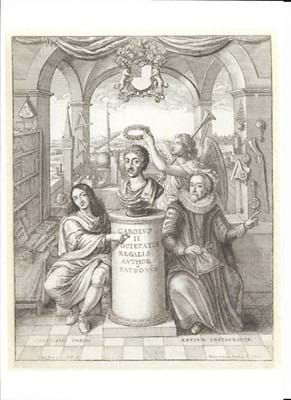

Bruce, a Royalist who resided in Bremen during the Interregnum, included Dutchman Christian Huygens (inventor of the pendulum clock in 1657) and fellow Scottish scientist Sir Robert Moray (1609-73) among his circle. The subject of pendulum timekeepers dominated their conversations.

At Bruce’s expense, Oosterwijck completed the clocks – each with a distinctive wedge-shaped case – in 1662, with a third subsequently made by the London clockmaker John Hilderson. The 1663 sea trials conducted on board ‘one of his Majesty’s pleasure boats’ by president of the newly founded Royal Society, Lord Brouncker, and Robert Hooke, produced mixed results.

By 1667, the idea of a pendulum marine timekeeper was sidelined in favour of spring-driven clocks.

What happened to these timepieces was unknown until the post-war era when, a decade or so apart, two near-identical movements emerged.

One unsigned example found in 1974 (perhaps the movement made by Hilderson in 1663) was sold to the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, for £100,000 in 2015. This clock now on offer at Dreweatts, signed by Oosterwijck, was published by Antiquarian Horology in 2006, following a nine-year research project.

It was later exhibited at both the Royal Society (2013) and at the NMM as part of the 1714 Longitude Act tercentenary.