Addressed to the philosopher Eric Gutkind, what has come to be known as the ‘God Letter’ was a private response to the recipient’s book Choose Life: The Biblical Call to Revolt, but stands as Einstein’s clearest and most important expression of his views on God, religion and man’s search for meaning, according to Christie’s New York (25/20/12.5% buyer’s premium).

Einstein had read Gutkind’s book, which, said the cataloguer, “presented the Bible as a call to arms and Judaism and Israel as incorruptible” at the prompting of the Dutch mathematician and philosopher, LEJ Brouwer. Although Einstein does try to find some common ground in his letter to its author, he is forthright in his response.

“The word God is for me nothing but the expression and product of human weakness, the Bible a collection of venerable but still primitive legends. No interpretation, no matter how subtle, can (for me) change anything about this.”

After citing the more liberal views of Spinoza, the 17th century Jewish Dutch philosopher, Einstein goes on to explain: “For me the unadulterated Jewish religion is, like all other religions, an incarnation of primitive superstition. And the Jewish people, to whom I gladly belong, and in whose mentality I feel profoundly anchored, still for me does not have any different kind of dignity from all other peoples.

“As far as my experience goes, they are in fact no better than other human groups, even if they are protected from the worst excesses by a lack of power. Otherwise I cannot perceive anything ‘chosen’ about them.”

When last offered at auction – at Bloomsbury Auctions in 2008, as part of a special 25th Anniversary Sale – the letter was estimated at just £6000-8000 but sold for £170,000.

Wisdom and consolation

On November 30, as part of a History of Science & Technology sale that included a major Richard Feynman archive to which I will return in another issue, Sotheby’s New York (25/20/12.9% buyer’s premium) also came up with a Bible that had belonged to Einstein.

The cataloguer argued that Einstein’s view of the Bible “…has in large measure been shaped – or perhaps misshaped” by the well-known letter to Gutkind, as evidenced by the inscription in this Bible given and inscribed (in German) by both Albert and his wife Elsa to Harriet Hamilton in 1932.

“This book is an inexhaustible source of living wisdom and consolation. Read therein and think on” Einstein wrote in his part of the inscripton. In 2013 the Bible had sold for $55,000 at Bonhams New York, but this time, estimated at $200,000- 300,000, it failed.

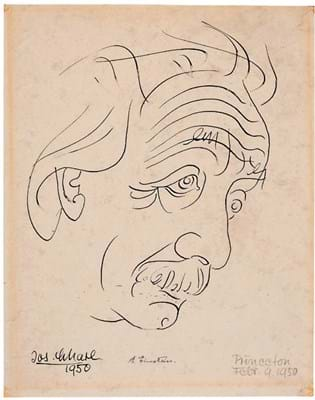

Two portraits of Einstein did sell, however. A doubly signed, simple ink line drawing of 1950 by Josef Scharl, an old friend for whom Einstein had stood as guarantor when, following the rise of the Nazis, Scharl sought to emigrate to the US, was bid to $26,000 (£20,315).

Signed in the mount by Einstein, a large-format example of a well-known photographic portrait by Roman Vishniac, made in 1951, sold for $45,000 (£35,155).

Aristophil dispersal

Last seen at auction some 35 years ago in New York, a signed autograph manuscript (in German) for an article in which Albert Einstein offered the wider public an explanation of his famous theories was a high spot in recent Paris sale.

Included in one of the many sales being by a group of French salerooms to disperse the huge Aristophil Collections, it was part of an Artcurial auction held on November 19.

The original text of an article published in a February 1929 issue of the New York Times, the manuscript, which showed numerous autograph alterations and amendments, had been estimated at €30,000-50,000, but sold instead at €299,000 (£266,110), including premiums, taxes, etc.

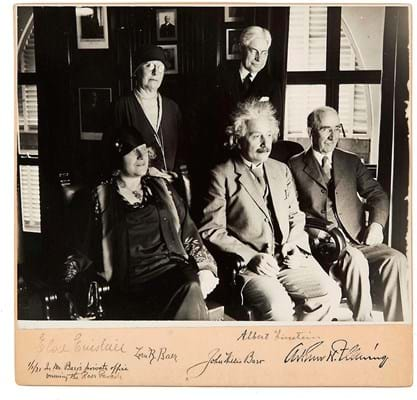

Sold at €6500 (£5785) in Paris was a photograph in which Einstein is seen with his wife, Elsa and others – all of whom have signed the mount – on New Year’s Day 1931, watching the annual Rose Parade in Pasadena, California, from an office window overlooking the street.

The Artcurial’s sale’s highest bid of €507,000 (£451,470) was made for a collection of manuscripts in which the eminent French mathematician and physicist Émilie du Châtelet (1706-49) recorded her researches into the work of Isaac Newton.

Du Chatelet’s translation of and commentary on Newton’s Principia…, posthumously published in 1759, is to this day regarded as the standard French version of that great work, and one in which she made her own important contributions to Newtonian mechanics.