The Schorsch family’s $10.3m collection sold by Sotheby’s across five sessions in January 2016 betrayed a broad range of interests – including a remarkable sensitivity towards mourning art.

The last two lots of the Sotheby’s sale – a gold brooch ($47,500) and a ring ($30,000) both said to contain strands of George Washington’s hair – had been the tip of the iceberg.

Mourning jewellery, much of it produced in the period in the formative years of the US, has traditionally found particular resonance among collectors in North America.

Anita Schorsch was the author in 1976 of Mourning Becomes America: Mourning Art in the New Nation, the book that accompanied an exhibition of the same name at the Pennsylvania State Museum and the Albany Institute of History and Art.

The couple had later established the Museum of Mourning Art at Arlington Cemetery in 1990 displaying much of the jewellery collection that proved a near sell-out at Freeman’s (25% buyer’s premium) of Philadelphia last week.

More than 150 lots

This assemblage of over 150 tokens of mortality, grief, commemoration and remembrance, sold as the opening lots of an American Furniture, Folk & Decorative Arts auction on November 15, brought together over 200 years of private and public expressions of death.

The collection had been designed to document western social change: from graphic ‘death is the master of all’ symbols of enamelled Stuart crystals, to the neoclassical ideals encompassed in delicately painted lockets and rings from the late 18th century.

Exceptional quality

As a general rule, the quality was exceptional. There were, for example, more than 20 of the rock crystal slides or pendants of the type made in England and France in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Usually, just one is a bonus.

They are among the most artful expressions of mourning – often functioning as both general ‘memento mori’ reminders of the brevity of life and memorials to the loss of specific loved ones. Provenances listed in the catalogue and in Anita Schorsch’s meticulous notes suggested many had been acquired through the Mayfair dealership SJ Phillips.

They made between $1000-4000 (£750-3000) apiece. Leading the group was the example worked with skeleton holding a bow and arrow flanked by the gold wire initials AD against hairwork ground. Key to its added appeal was the inscription to the reverse, A Duncumb Ob 17 Feb 1709 Atat 58.

The high rate of mortality was a brutal fact of life in this period – and not just for the poor of society. Tragically, despite her 17 pregnancies, only one of the children born to Princess Anne (the future Queen Anne, 1665-1714) survived infancy. Prince William, Duke of Gloucester also died, aged 11.

A 1½in (4cm) oval pendant – acquired in 1994 from Ares Antiques in Manhattan – featured a watercolour miniature portrait of Prince William, with a skull at his shoulder and the inscribed date 30 July 1700.

It was to prevent a Catholic succession that the following year Parliament enacted the Act of Settlement which in 1714 would transfer the British throne to Sophia of Hanover and her Protestant heirs.

In generally good condition, with still vibrant colours, this great rarity estimated at $2000-2500 took $28,000 (£21,000).

Sold at $4000 (£3000) was an unusual matching pair of gold and enamel mourning rings dated 1722. Each set with skull and crossbones beneath a faceted glass stone, both carry the inscription G Weld Esqr Obt. 21 July 1722 Aeta 20.

Most gold and enamel mourning rings of the later Georgian era are presumed to be English. In fact, a thriving trade for these rings existed in the cities of colonial and postcolonial North America.

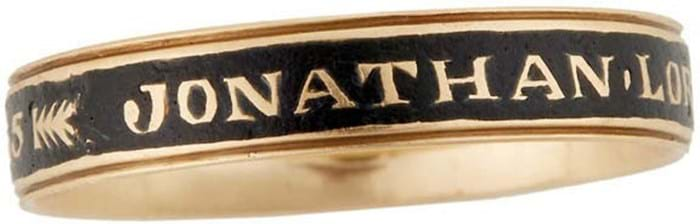

Gold and enamel ring for Jonathan Loring dated 1800, probably Boston – $650 (£490).

A ring with the inscription Jonathan Loring Ob 10 Mar 1800 Ae 55 was thought to have been made in Boston c.1800. It perhaps refers to a tailor born in Hull, Massachusetts, on November 18, 1744, and husband to Margaret Davidson (d.1822), who died that year. Last sold at Christie’s in January 1996, it took $650 (£490).

A ring set with a skull under faceted crystal marked another member of the Loring family. It too was probably made in Boston. The scrolling band was inscribed N Loring OB 15 May 1765 Ae 9m – the white enamel ground underlining the fact that the deceased was an infant. It took $3750 (£2810).

Neoclassical sensibilities

As the 18th century faded, mourning jewellery became less macabre. Skulls and bones gave way to the softer symbolism of weeping willows, monuments, winged putti, women in lamentation or the occasional ship sailing towards the afterlife. Painted ivory and hairwork mounted in gold was the fashionable medium.

There were some very fine examples – with two of the best pictured above. Acquired through SJ Phillips, the octagonal form pendant depicting a woman with two children beside an urn on plinth inscribed Not Lost But Gone Before sold at $4500 (£3375). Bought from Baltimore dealer Arthur Guy Kaplan in 1983, the unusually large oval pendant with fine polychrome decoration took a multi-estimate bid of $9750 (£7310).

Depictions of male mourners are far less common than the conventional female mourner.

Sold at $3750 (£2810) was a brooch – probably made in Boston – that was painted with a gentleman in contemporary attire weeping beside an obelisk inscribed Weep Not for Me But For Yourself. A plinth included the name of the deceased SM/SH Barker and the date July 1794. Anita Schorsch had bought it at Sotheby’s New York in 1987.

Another American-made pendant with a beaded gold surround of a similar date painted with a female mourner and two ships sailing in the distance took $3250 (£2440).

A plinth decorated with stacked initials AC, TC, AC, IC, PC and AC implied a moment of extraordinary loss.

The specialist's view - we chat to Nicola Whittaker of Fellows

The original makers or owners of most pieces of antique jewellery are destined to remain anonymous. An inscription can thus be a powerful thing – a tangible connection to an individual from the past and a glimpse into a life once lived.

Mourning jewellery – easily stereotyped as morbid and macabre rather than tender and poignant – appeals precisely on this level. It is occasionally bought to wear but more typically as a connection to the past.

“We research the names as much as we can,” says specialist Nicola Whittaker of auctioneers Fellows.

“Sometimes it really pays dividends. We don’t necessarily price inscribed pieces differently – condition is usually the key factor as enamel often cracks and painted ivory is prone to water or light damage – but anything that gives an insight into the individual is a bonus.”

This can be as straightforward as a name and date that points to a historical figure: for instance, the George III ivory pendant marking the rediscovery of Edward IV’s tomb in 1789 that sold at Fellows for £900 in January 2014, or a George III gold and enamel ring recording the death of Captain Charles Jolliffe of the Royal Welch Fusiliers at Waterloo (£560 in November 2015).

However, the names of wholly obscure figures plucked from an era before photography can be equally evocative.

Whittaker recalls research into a gold, ivory and enamel marquise-shape ring inscribed Peter Ramsey Ob: 27 Oct 1781 Ae 48 uncovered an enterprising soul who was Registrar in Chancery and Clerk of the Patents in Jamaica and is buried in St Catherine’s church in Spanish Town. “What a life he must have had,” Whittaker remarks. It made £580 in March 2016.

Away from the heights of the Schorsch collection (see main story above), this is an eminently affordable area of collecting.

Hairwork is not for everyone – and even in the Victorian era the trade was blighted by occasional scandals when a deceased’s locks were found to have been replaced by those of a stranger or horse hair. An estimated 50 tonnes of human hair a year was imported into England for use by the country’s jewellers in the mid-19th century.

The typical Georgian or Victorian gold and enamel mourning ring – usually paid for by the person commemorated with a list of intended recipients stipulated in his or her will – is currently priced in the low hundreds.

As early as the mid-18th century, newspaper ads were boasting the speed with which such rings could be made and by the Victorian era – when all manner of black jewellery from Whitby jet to gutta percha was fashionable – mourning rings and brooches were mass produced and held in stock.

“We include them in our most accessible auctions – the regular Vintage Jewellery and Accessories sales – with some lots priced as low as £50-80,” says Whittaker. “Surprisingly, perhaps, we find they prompt particular interest on social media. People appreciate these aren’t just any piece of jewellery.”