Modern Maps

The 20th century was the golden age of the printed map. Literacy, global conflict, travel opportunities and cheaper printing techniques combined to ensure that maps permeated every aspect of life for the first time. And in the 21st century, as interest grows rapidly among dealers, collectors and museum curators, the market is beginning to respond.

It took the arrival of the internet to turn on its head the accepted view that maps which were printed 300-400 years ago must be intrinsically rarer and more commercially valuable than anything ‘mass produced’ in the 20th century. Not so.

No early, hand-printed map could be described as common but, to take one mainstay of the UK map trade as an example, anyone looking for a 17th century John Speed county map is likely to be offered a choice.

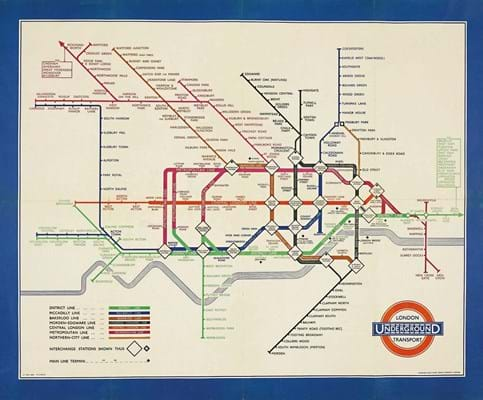

On the other hand, the hunt for the earliest edition of Harry Beck’s London Underground diagram – one of the most innovative and influential examples of 20th century cartography and design – is likely to be far tougher.

Even the ordinary pocket-sized passenger version, printed in 750,000 copies in January 1933, is now highly collectable: expect to pay close to £2000.

But the original run of quad royal-sized posters, although printed in 2500 copies in March 1933, would nearly all have been pasted directly to station walls and scraped off as soon as they were obsolete. As far as we know, just a couple of spare copies were retained for the official archive. Just such a duplicate from the London Transport archive was sold by Christie’s in 2012, the only one to appear at auction. It realised £8500, which now seems cheap: a realistic estimate today would be at least double.

Beck’s map is a useful reminder that, in 2017, much of the 20th century is more remote than we think. And with so much material offered online, if a map cannot be found it is probably genuinely scarce.

No longer the preserve of a privileged elite – some were simply given away – most of the millions of maps printed in the 20th century were discarded after they had served their immediate purpose, or survived a generation or two before they were thrown into a skip.

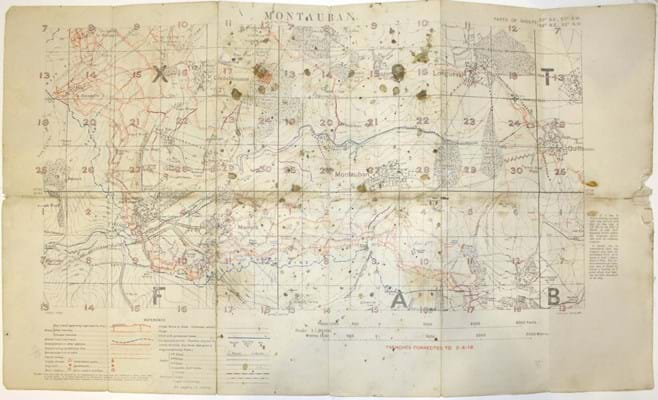

While ‘modern firsts’ and modern literature has been a significant part of the rare book trade since the 19th century, cartography from the period was preserved by pioneering collectors, often keeping to very specific themes such as railway maps or First World War trench maps. We are indebted to them, if also constrained by what they considered worthy of preservation.

We cannot know everything we’ve lost, but until recently our national map collection in the British Library lacked one of the earliest printed UK gay city maps, the Gay-Z map of London published by the Man to Man bookshop in Notting Hill c.1977, and the earliest map of Beatles tourism in Liverpool, from 1974.

Maps such as these are now breaking out of the ‘cartographic curiosity’ category and have attained significant value.

Persuasive Mapping

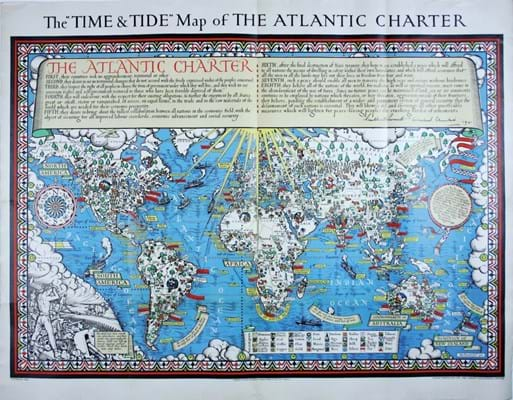

There is particular interest in ‘persuasive’ cartography, where finding the way from A to Z was not the primary purpose. There are plenty of takers for early airline route maps, or posters advertising rail travel.

Among the most striking propaganda maps are the cartoon maps of Europe which reached the peak of their popularity on the outbreak of the Great War.

Very few of these post-date 1915. As the carnage extended into a second year, maps of national stereotypes in human or animal form pushing and shoving one another across borders stopped being funny. Some are particularly rare: images of a benevolent tsar would have been dangerous souvenirs in post-revolutionary Russia. Most are now four-figure items.

Part of another rich seam are the wryly comic pictorial maps pioneered by MacDonald Gill with his ‘London Wonderground’ map of 1913. Sold to the public in various editions until the 1930s, good examples now sell for £2000-3000.

There is plenty yet to discover. The descendants of Kerry Lee, a poster artist active between the 1930s and 1950s with a highly distinctive style of pictorial mapping, recently got in touch with a wealth of information about his life and work. With 20th century maps, if we don’t know the answer, it’s not always too late to ask.

Plenty of 20th century material remains highly affordable. Assisted by generally rising living standards including the advent of the family car and holiday entitlement, the Ordnance Survey embarked on a commercial drive after the First World War. Early OS regional maps, mounted on linen with pictorial covers created by artists such as Ellis Martin and Arthur Palmer, are worth collecting in their own right.

Often saved in case they were useful again, for the most part they can still be found in fine condition, so collectors should buy the best examples they can. Prices typically range from £10-30. There are OS rarities, of course.

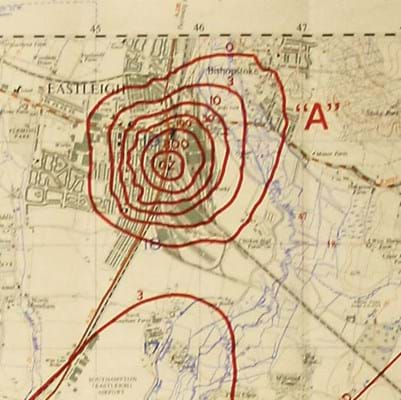

Cold War maps, such as a 1957 sheet overprinted with the potential effects of a nuclear blast over Southampton, where the OS had its headquarters, would doubtless have induced panic if circulated at the time.

Condition presents its own special issues with 20th century maps. For reasons of paper quality, it can be necessary to make greater allowances for massproduced maps than for those printed by hand before 1800.

Context is also key. A trench map which has survived the mud of Flanders is likely to show signs of use, but a souvenir of the coronation of George VI, printed in large numbers and preserved as a memento in many thousands of households, might well be pristine.

Judgments also have to be made as to whether annotations detract from, or add to, interest and value. Has an ordinary 1926 passenger map of the London Underground, carefully inscribed by a former owner to show every station closed in the General Strike, been defaced, or do such marks enhance our understanding of the map and its user?

Lines drawn on maps can have seismic consequences. On display at the recent British Library exhibition Drawing the Line, which showcased maps as witnesses to contemporary events, was a copy of Stanford’s map of ‘Turkey in Asia’. It was marked up in coloured pencil to show the territorial boundaries proposed in 1916 by Mark Sykes and François Georges-Picot.

At this year’s London Map Fair at the Royal Geographical Society (see right), collector and topographer Simon Morris will give a lecture entitled The Other Side of the Map detailing the impact of corrections, annotations and marks of ownership.

Traditionally in map collecting, clean, unmarked specimens attract a premium. But some of today’s collectors are turning received wisdom on its head.

Tim Bryars of Bryars & Bryars in Cecil Court, Covent Garden, is co-author of A History of the 20th century in 100 Maps with Tom Harper, curator of antiquarian mapping at the British Library.

London Map Fair

Twentieth century cartographic material has become an important part of what’s on offer at the London Map Fair, now the largest as well as the oldest specialist map fair in the world.

Held annually at the Royal Geographical Society near the South Kensington museums, this year’s event takes place on the weekend of June 17-18, and with over 40 international exhibitors it is one of the best places to handle a wide range of material and meet expert dealers.

Propaganda maps from the first and second world wars rub shoulders with maps from the age of discovery and exploration.