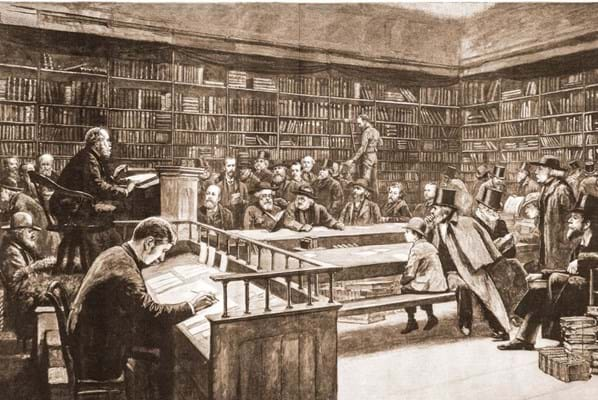

A print hanging in the London office of the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association (ABA) gives a glimpse – perhaps an idealised one – of how the book trade used to be.

The venue is Wellington Street, just off the Strand. The date is 1888 and the scene is a book auction at Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge.

An inscription to the margin identifies 16 of the bearded gentleman present as the leading booksellers and collectors of the period – men that 18 years later would meet over lunch at the Criterion restaurant in Piccadilly to create what would become the art and antique trade’s most venerable association. Those badges displayed today by dealers of all descriptions began here.

Today’s members of the ABA operate in a marketplace that would be scarcely recognisable to a Victorian or Edwardian bookseller.

The closure of much-loved bookshops, the movement of the trade online and Doomsday predictions surrounding an ageing collecting audience all vex the grey matter.

And yet the concerns over professional standards that prompted the foundation of the ABA (or the Secondhand Booksellers’ Association as it was first called) are more relevant now than ever.

With the advent of the internet, anyone with access to a computer and a few books can set up as a rare bookseller.

It is a common refrain that there are more people selling books than ever before but fewer people selling good books.

The issue when buying from aggregator sites such as eBay or AbeBooks is not that you will send your money and get nothing in return, more that a book from an inexperienced seller may be incorrectly described.

Many leading booksellers want to send a clear message that their books are catalogued with expertise, excellence and experience. Currently the ABA is pushing to have its own designated ‘members only’ space on Abe.

“A good bookseller is more than a merchant: they are a source of advice, encouragement and accumulated wisdom”

The internet has impacted collecting in this sphere in other ways.

With more collectors and dealers having direct access to more old books than ever before, prices at the lower end have dropped significantly. It is a bête noire of dealers to see a potential buyer reaching for a smartphone to check if a book is available for less elsewhere. With more competition, it no longer pays to be a purveyor of the ordinary.

More profoundly, while the collecting instinct remains, what people choose to collect is in a state of flux.

Tastes were once dictated by what dealers and their established customers thought was worth cataloguing. Now, as the cupboards of the 20th century are cleared, it could be a wartime map or a favourite childhood novel that fires the modern imagination more than a leather-bound classic of 18th century literature.

If some older members of the dealing fraternity come to this debate with a lot of baggage, then a generation of ‘born digital’ traders is now emerging keen to tap in to the explosion of interest in material and visual culture that the internet has spawned.

Camilla Szymanowska, ABA secretary, observes: “It is necessary to look horizontally at what you might sell. But the roactive type of bookseller has adapted well to these subtle changes in taste.”

The advent of the portal site two decades ago had provoked polarised reactions within the rare book trade: that dealing and collecting would wither as a way of life; and that the global marketplace would be a cash machine for savvy traders. Neither prognosis has proved wholly accurate.

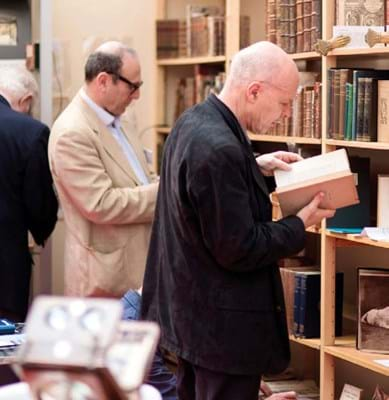

It is still predominantly at the fair and in the shop where dealers meet clients and establish the brand loyalty that can so often be lost when they are just another trader on a computer screen.

As Rich Rennicks, writer for the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association of America, puts it: “A good bookseller is more than a merchant: he or she is a source of advice, encouragement, and accumulated wisdom. A trusting connection to a dealer will yield the best collecting results.”

Organising fairs and seminars on book collecting, where dealers and customers can meet face-to-face, remains a key part of what associations do and are a primary draw for many members.

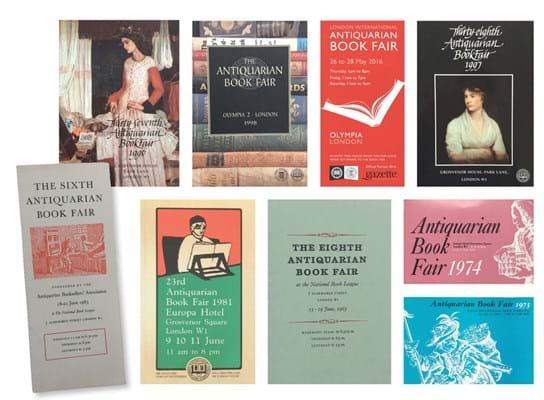

The ABA has run fairs for its members since 1958 (the first London Antiquarian Book Fair held at the National Book League in Albemarle Street). Its prestige events have been complemented since the 1970s by the galaxy of more down-to-earth shows organised by The Provincial Book Fairs Association (PBFA).

Relations between the two camps were not always harmonious but the ‘us and them’ mentality has begun to fade in recognition of a common cause. Many UK booksellers are members of both associations.

For the second time, this year’s two major ‘competing’ London summer events – the ABA fair at Olympia (June 1-3) and the PBFA’s flagship event at the ILEC Conference Centre in SW6 (June 2-3) – will be joined by others under the marketing umbrella Rare Books London. May 23-June 12).

International Liaisons

Promoting London as a ‘destination’ for bookish culture is designed to appeal beyond the traditional buying audience.

It was repeated in March for the first Rare Books Edinburgh festival centred around the Edinburgh Book Fair, opened by bestselling author and king of ‘tartan noir’, Ian Rankin.

It was the Scottish fair that first pioneered joint activity between the ABA and the PBFA – a model which was later used in Dublin and is now being tried in Bristol (June 30-July 1). The result is a broad brush of dealers from top London names to local members.

In this unique space there is surely more to unite associations than divide them.

An international umbrella organisation for rare book dealers is 70 years old this year. The International League of Antiquarian Booksellers was originally conceived by then Dutch association president, Menno Hertzberger, who, as a Jew, had spent part of the Second World War in hiding.

He dreamed of common ground and understanding: “Five long years of war had put up barriers between nations,” he recalled. “This enforced chauvinism or worse, hatred. Only through mutual interests could nations be brought together.” For antiquarian booksellers, the mutual interest was books.

ILAB’s core principles of establishing open markets and fostering friendships were first agreed in 1947, and then formally incorporated in Copenhagen in September 1948. The 10 founding countries have since been joined by a dozen other national associations.

The 42nd ILAB congress in Budapest last year (the next will be held in February 2018 in Pasadena) adopted an idea put forward by Sally Burdon of the Asia Bookroom in Canberra, and Massachusetts dealer Stuart Bennett. They designed an international one-to-one mentoring programme to plug a gap that has opened since ‘first rung of the ladder’ opportunities for would-be book dealers have declined.

Burdon, described by a colleague as “probably the most important woman in the book trade”, is keen to harness the goodwill of ILAB’s 2000-plus members across 32 countries. “There is nothing new about this. Throughout the history of the trade booksellers have helped each other,” she says. “But as large bookselling firms grow fewer, apprenticeships are on the wane.“

“Throughout the history of the trade booksellers have helped each other”

In this day and age, Burdon reminds us, communication across the world is easy and inexpensive. “We can now envisage a Dutch mentor supporting a young American bookseller, an American mentor helping a young Russian bookseller or an Australian mentor chatting regularly with their mentee in Malaysia.”

In the rare book trade the image of Victorian Englishmen in Dickensian surroundings has been a difficult one to shake. But slowly it is happening.