The principal attraction was an archive of designs, watercolours and other material relating to the construction of the first Thames Tunnel, which sold at £160,000.

Earlier attempts or plans to tunnel under London’s river, made by Richard Trevithick and others, had failed and many believed that it was not possible.

Brunel, however, planned to use a hydraulically powered tunnelling shield that he had devised and patented for a proposed tunnel under the River Neva in Russia.

Work began in 1825 on what was to be a tunnel for horse-drawn traffic with the sinking of a vertical shaft on the south bank of the river, at Rotherhithe – as seen at left in the illustration top.

Flooding was a constant problem and danger. With the funds of Thames Tunnel Company rapidly consumed, work ceased and the tunnel was sealed up in August 1828.

Brunel resigned from his position, frustrated by the continued opposition to his methods by the company chairman, and moved on to other civil engineering projects.

These included helping his son, Isambard Kingdom, with his design of the Clifton Suspension Bridge – and the younger Brunel in his turn was to work on his father’s tunnel.

Four years later the obstructive chairman was removed and in 1834 the government agreed a loan of £246,000 to the Thames Tunnel Company.

The old, 80-ton tunnelling shield was removed and replaced by a new and improved 140-ton model and tunnelling was resumed, but there were still instances of flooding when the pumps were overwhelmed.

Miners were affected by the constant influx of polluted water, and many fell ill or died in accidents.

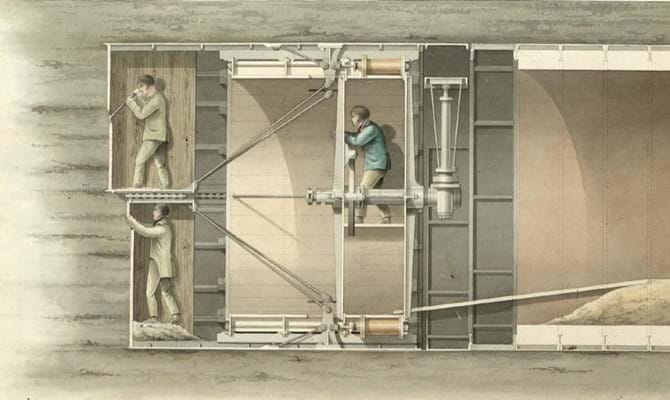

The tunnel was progressed by means of a tunnelling frame, divided into three compartments or cells, each 3ft (91.5cm) broad and just over 21ft (6.5m) high. Twelve such frames therefore provided 36 cells in which the miners could work independently of each another.

Bricklayers, working with their backs to the miners, allowed the double operation of mining and bricklaying to be carried on simultaneously and those who followed the tunnelling machine had, by the time the river was crossed, laid some 7.5m bricks.

Finally, the tunnel approached the Wapping shore and work began on sinking a vertical shaft similar to that in Rotherhithe.

The Thames Tunnel was officially opened in March 1843 and Brunel, despite ill health, took part in the opening ceremony.

Within 15 weeks, a million people had visited the tunnel, among them Queen Victoria and Prince Albert.

Although originally intended for horse-drawn traffic, the tunnel remained pedestrian-only and in 1865 was acquired by the East London Railway Company. Later still it became part of the London Underground system, and now the London Overground network.

Other projects in the Brunel archive included designs for London’s docks, bridges, timber yards and associated machinery, along with a steam powered sawmill for the Chatham dockyards, even a machine for cutting furniture veneers.

Dating from the elder Brunel’s earlier years in the US, the archive also included proposed elevations for a Capitol building in Washington, a country house and a bank, as well as machines aimed at improving navigation on the Mohawk River.