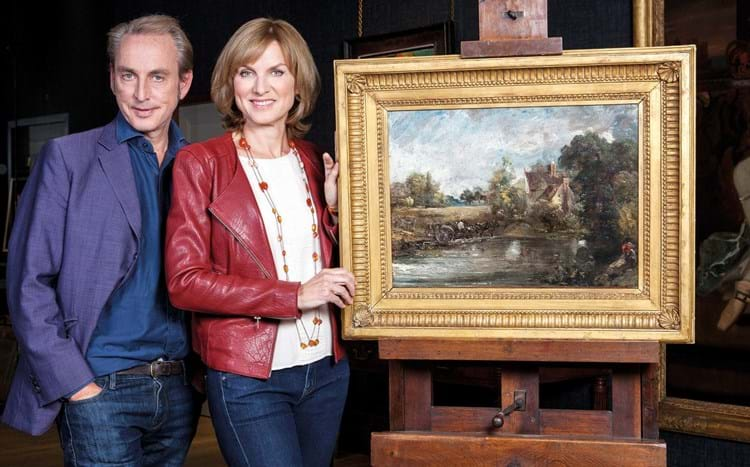

A meeting in a basement room in a London gallery is the culmination of months of investigation and hard work for TV art detectives Philip Mould and Fiona Bruce.

Filming is in progress at Mould’s Pall Mall gallery and the discussion involving art dealer Mould and presenter Bruce – centring on a sketch possibly by John Constable located in Los Angeles, and following a 10-day road trip round Australia looking for clues for another artwork – is the most sedate part of the BBC’s Fake or Fortune?

The hit sleuthing show is back on our screens this month and this series, the sixth, includes artworks that may, or may not, be by Constable, Australian artist Tom Roberts, Paul Gauguin and Alberto Giacometti.

It attracts upwards of 5m viewers in the UK, where it airs in the prime-time slot of Sunday at 8pm, and is also broadcast in Canada, New Zealand, Sweden and Germany.

For the uninitiated, the modus operandi is this: Mould and Bruce travel the world tracking down the provenance of works of art with the aim of proving their authenticity.

Helped by evidence from family collections, museums, archives and laboratories, the work is then presented to the relevant authorities for the final verdict.

With BBC series producer Robert Murphy, the pair talked to ATG as they completed the final episode of the sixth series ahead of the show’s return on August 20.

ATG: With 23 programmes under your belt, is the appetite for the show still as strong?

Philip Mould: The programme has really come of age. I think we are now the most-watched arts programme globally. These shows are conclusion-sensitive, but the repeats have generated just as much interest. We had 4.35m people watching a repeat earlier this summer.

Why do you think it is so popular?

Robert Murphy: There are moments of pure discovery that any drama scriptwriter would love to have.

Mould: People seem to like the arcane aspects of the research, forensics and history combined with a twisting plot. As the process is normally seen through the eyes of the owner, for whom there can often be great jeopardy, an hour of art history seems naturally to morph into the type of whodunnit that captures the imagination.

And the first programme on a possible Constable sketch related to The Hay Wain – the art historical and commercial stakes are among the highest we have ever been involved with.

Do you think the public’s appetite for complex art programmes has been underestimated?

Fiona Bruce: We wouldn’t be the BBC’s most popular art series if the public did not have an appetite, because we absolutely go into the technical, forensic detail. We don’t try to simplify it.

We show the complexity of the research and the fact it doesn’t always lead to a straightforward answer.

Mould: I often use the analogy of the pathologist’s report in a murder case which can be extremely complex. But viewers are very happy to engage if they are drawn into the narrative of the whodunnit.

Why should members of the trade watch the series?

Mould: What we do is to turn the spotlight on something every serious art and antiques dealer has to consider – the process of authentication in a world full of followers, imitators, pasticheurs and fakers.

Furthermore, as art historical science and analysis becomes more sophisticated, so too do those who wish immorally to profit from it.

For me as a dealer, it has certainly been interesting to follow the latest developments in authentication processes.

Will we see artworks other than pictures in the next series?

Mould: The innovative part of this new series is that we are doing a three-dimensional piece of art – a sculpture – that could be by Giacometti. But the key to this programme is about measuring artistic prowess as opposed to artisan prowess.

So if we are going to do more objects there has to be a powerful third dimension – the human associations such as provenance or just the rarity, scarcity or intangible aspect of what it is. After all, it is an art programme, not an antiques programme.

Murphy: [What we feature] will depend on the art historical importance of it and the value.

Bruce: Any piece has to count as an artwork of some kind.

It is not enough to say ‘this was Cromwell’s bed’. It needs to be a bed that has been made by a carver or maker of such significance that it has an art historical impact, not just that it was owned by an important person.

How did the series start?

Mould: I was working on the BBC’s Antiques Roadshow around seven years ago when a painting brought in by a fisherman who had found it on a rubbish tip turned out to be by the American impressionist painter Winslow Homer.

We had the idea of a show that would utilise the lessons of the Roadshow and graft it with [the theme of] my second book, Sleuth, which was all about hunting down sleepers.

Sleuth was, in fact, the series’ working title and I did a two-minute taster commissioned by Simon Shaw, the Roadshow’s producer, to show the heads of arts and factual in London how it could be done.

We were not aiming it at BBC1 or a mass audience, but rather something a little more rarefied for BBC2.

It has to be said the internal response from the commissioners – and then its reception by the public – took us by surprise.

How do you plan each episode?

Murphy: When a show goes out we get a flurry of emails. We filter through these and get in touch with people that may have something interesting. We ask for more images and information and look at how they acquired the pieces. With some of them you can quite quickly see they are copies.

But we always say that when one piece of real quality appears it absolutely stands out. A piece from Belgium last year (an early work by Willem de Kooning) just leapt off the screen. But the items that make it to the show are just the tip of the iceberg.

Mould: The programme unfolds in real time. We generally don’t know where things are going.

Murphy: It is always amazing where things take us. We will often start digging into a story and it can take a year or two to come to fruition and into the production process.

Bruce: Like with the Lowry in series four – we were really stuck for quite some time. And then suddenly, we had a breakthrough.

Mould: And with the Constable in the new series. [The process of discovery] was just marvellous.

Bruce: But there was no way of knowing that at the outset.

Do you operate within time constraints?

Murphy: Sometimes we dig down into things and you find an answer too easily and can too quickly solve who the sitter or who the artist is. That doesn’t work. The story has got to sustain an hour’s television.

Mould: Yes. A slam-dunk doesn’t make great television.

Bruce: We don’t get many, though. We don’t have an embarrassment of riches on slam-dunks.

Murphy: Sometimes we will try to work on something but it is not possible to take it further, due to not having the co-operation of the artists’ estate for instance. When that happens, it is a shame.

Is there one elusive artwork you’d love to feature?

Bruce: There’s one I am really keen to make a programme about, but unfortunately it is in police custody. Should it come out of police custody then we are on!

Fake or Fortune? in numbers

23 episodes

6 series

9 months of production

1000+ submissions for each show

500 hours of filming for each series

5 countries visited for latest series

How do the presenters deal with the disappointment of a committee not agreeing with their view?

Philip Mould says: “Take the Monet from the first series we did. It looked like a Monet. It felt like a Monet. But the experts who actually do Monet say it didn’t look Monet enough. By the way, I still think it is a Monet. But ultimately attribution is an emotional, human decision.

“You garner all the information: the forensics, the provenance, the factual details. The provenance is fact, the technical elements are fact. But then when you move into stylistic areas, it is to do with the quality of argument. It is also to do with comparison.

“And you can have a committee which, for whatever reason, fails to see it as you do. This is where we see the area of the illusion (in art). The intangible, magical area of art. This area is part of the appeal of the show.”