Overshadowed by the Chinese boom, another market which has emerged over the past few years from the world of scholars and museum curators into the high-priced field of collectors is tribal art.

Turbo-charged by the worldwide reach of the internet, the market is today of considerable importance to UK auctioneers with scarcely a week passing without ethnographica shining somewhere in the UK.

A marine ivory necklace from Mangaia, the southernmost of the Cook Islands (£99,000 at Ewbanks in Surrey, in December), a Maori putorino or bugle flute (£140,000 at John Nicholson’s in February) and an Easter Islands figure (£95,000 at Dreweatts in March) are three recent spectacular cases.

Two specialist sales underlined the point: that at Woolley & Wallis (22% buyer’s premium) in Salisbury on March 1 and, at the other end of England, the March 8 sale held at Tennants (18.5% buyer’s premium) in Leyburn.

Join the Wiltshire tribe

The Salisbury event was one of the biannual specialist sales which expert Will Hobbs has been holding since 2014 and the figures reflected the buoyancy of the market – 93% of the 490 lots got away to a hammer total of £396,000.

“Tribal material is seen as modern art,” comments Hobbs. He says finely crafted material with aesthetically pleasing shapes can, when mounted in one’s home, become conversational pieces at last the equal of contemporary sculptural works.

Obvious examples are the wood and hide headrests made across Eastern and Southern Africa.

Usually about 5-6in (13-15cm) high, with a dished wooden rest supported by two or more variously carved supports, they vary in design and quality from the finest 19th century figural examples to the more ordinary.

In March, those at Salisbury were in the latter category – one from Kenya’s nomadic Turkana people which took £420 and a Zulu example at £520. Run-of-the-mill examples though they were, they both tripled the estimates.

The market’s favourites are those made by the Shona people of Zimbabwe which can make serious money. Back in July 2015 a 19th century headrest with the support in the shape of an antelope took £23,000 at Bishop & Miller of Stowmarket (ATG No 2200).

The Shona pieces at Salisbury were more in the budget category with a mid-estimate £1000 securing the best one, a simpler 5in (13cm) high example on geometric supports.

Top of the rest was one from South Africa, possibly Tsongan, which sold to a USA buyer at a quadrupleestimate £1600.

An attached label was a reminder of the delicate aspect of collecting tribal pieces, particularly African ones. It’s difficult, for instance, to look at a superb piece of Congolese art without remembering Belgium’s appalling record there.

The label to the headrest read Kafir Pillow. The term actually means a non-Muslim but, certainly from the late 19th century onwards, in colonial Africa it was used with more offensive connotations.

Much of Africa’s art has remained the preserve of the French and Belgian market although there are notable exceptions including the 16th century Benin head of a youthful oba which was sold last year for a “substantial seven-figure sum” in a private treaty sale negotiated by Woolley & Wallis in association with London & Paris specialist dealer Entwistle (ATG No 2275).

However, the strength of the British market is more in the South Seas. UK auctions have long seen items brought back by colonial servants come onto the market and such pieces still emerge from attics from time to time.

Known collections

Increasingly the sources of new pieces on the market are from known collections with buyers putting a huge value on provenance “almost above everything else” says Hobbs.

He was in the happy position of offering just such a collection – part of the vast and eclectic material compiled by the late Seward Kennedy, much of which was auctioned last November by both Christie’s in London and by Stair Gallery of upstate New York in February.

Contrary to the traditional wisdom that it is necessary to get a feel of a piece both literally and figuratively before making a judgment as to age, with a good history tribal aficionados feel confident about buying ‘unseen’ online.

“Prospective buyers do come to view days and sale days, many flying in from abroad,” says Hobbs. “But it is surprising how many will look at lots online and buy on the strength of the provenance.”

A shield of one-time headhunters the Kenyah people of Borneo came with a Victorian history.

The 3ft 9in (1.15m) wood, hair and rattan shield, painted with the eyes of a mythical monster to the front and ancestor figures to the reverse, was among the pieces brought home by Charles Hose, the civil servant in charge of the Baram River area from 1888-99.

During his governorship he brokered peace between the headhunters and meanwhile collected plants and animal species for the ‘White Raja’, Charles Brooke.

He also amassed a small collection of anthropological objects some of which are now in the British Museum and the Museum of Archeology and Anthropology at Cambridge.

The mask sold a shade under estimate at £9500 but any disappointment at the price was countered by the satisfaction of seeing it go back to Sarawak.

South Seas clubs were, as so often at UK auctions, steady sellers.

From Melanesia, a 2ft 5in (74cm) Vanatu wooden club with plaited grass, carved spheres, spikes and disks took £2800 against a £300- 500 estimate and a 17in (44cm) long Fijian throwing club with bone inlay doubled expectations at £3600.

The ace of clubs was a 3ft 6in (1.08m) long Samoan pole club carved with zig-zags and geometric patterns which went to a US buyer at £7200 against a £600-800 estimate.

Going more in line with expectations was a 19th century 4ft 1in (1.25m) long Austral Islands paddle with a leaf-shaped blade carved with sun motifs and a flared terminal carved with eight dancing girls. It went to a Dutch buyer at £7000 (estimate £4000-6000).

A 3ft (91cm) tall Australian Aboriginal parrying shield with all-over carved decoration to the front and an integral handle to the chamfered back, returned to Australia at £5800 (estimate £2000-3000).

Overseas buying was a significant feature of the sale but the highest priced lot, a late 19th or early 20th century Santa Cruz feathered currency roll illustrated on these pages, stayed in the UK.

The 3ft 3in (1m) wide roll comprised coils with red honeybird feathers centered around bark rings, one inscribed 9. Henry Mepulule, and was hung with strands of shells.

They were used to mark important financial transactions.

A mounted and glazed example provenanced to a Solomon Islands missionary was one of the surprises at W&W’s February 2015 sale when it took a ten-times estimate £20,000.

This latest uncased offering was pitched at £5000-7000 and eventually sold at £18,000 to a UK collector against a determined Belgian underbidder.

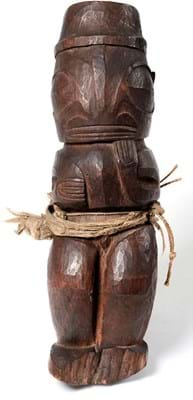

Tennants’ £20,000 Tiki

Tribal pieces from a good private collection were also the major draw at one of the regular Militaria and Ethnographica sales at Tennants on March 8.

Two of the pieces which “exceeded all expectations”, according to auctioneer David Hall, are illustrated here.