Bonhams' (20/12% buyer's premium) latest single-owner English ceramics auction, the Susi and Ian Sutherland collection of English blue and white porcelain, held in their Bond Street rooms, was just such an event.

It ticked all the right boxes and with just enough competition for a handful of its most popular elements to provide some saleroom drama. The plain statistics are as follows.

The all-day sale on October 3 saw 342 of the 375 lots sell (91 per cent) for a hammer total of £438,640 (94 per cent by value).

The second-floor saleroom was full for the event. There were some commissions left and heavy-hitting phone bids provided the aforementioned drama, but the bulk of the buying came from the room.

The Sutherlands were friends of the revered collectors the Watneys and well known through associations like the English Ceramic Circle. So the sale drew out the usual trade faces and a large number of private collectors who are key ingredients to the overall success of these events.

So much for the bare bones, but what was the distinctive character of this collection that made it worthy of Bonhams' single-owner, hardback catalogue treatment and of so much buying interest?

Watney in microcosm

As noted previously, this was a market-fresh collection with the bonus of a provenance stretching back to the late 1960s and a clear reason for sale (the death of Ian Sutherland last year a decade after his wife Susi). The Sutherlands focused on early, academic blue and white painted wares from the first decades of porcelain manufacture in England in the 18th century or, as their son Alastair put it, "the incunabula of English porcelain…. early experimental pieces brimming with imagination and romance".

This made it a sort of mini Watney collection and the sale a microcosm of the Watney triple-sale series held in the same rooms at the turn of the century.

Like Bernard Watney, the Sutherlands didn't have an enormous budget, which imposed some constraints, notably in condition terms, but they were tenacious.

Interestingly, although they occasionally bought at auction, they mainly bought through the trade: from dealers in Portobello, from the Wests and the Andrades in the West Country and from Simon Spero in Kensington Church Street, among others.

The one disappointment in an otherwise excellent catalogue is that, as most auctioneers have a convention of only putting provenance references to auction purchases in individual catalogue entries, only a few details of these dealer provenances featured. They would have added to the catalogue's interest and value as a record of the collection.

Notwithstanding this quibble, there was enough information in the individual entries, and Alastair Sutherland's well-conceived introduction set the collection in context and identified its creators' tastes. These seemed to combine personal preference with what was fashionable and academically stimulating at the time.

This meant an emphasis on Bow, Longton Hall, Lowestoft, an especially good representation of Limehouse and the various Liverpool outputs. There was also an emphasis on small items like butter boats, cream jugs and pickle leaves; pieces which chime with current collecting tastes when space is at a premium.

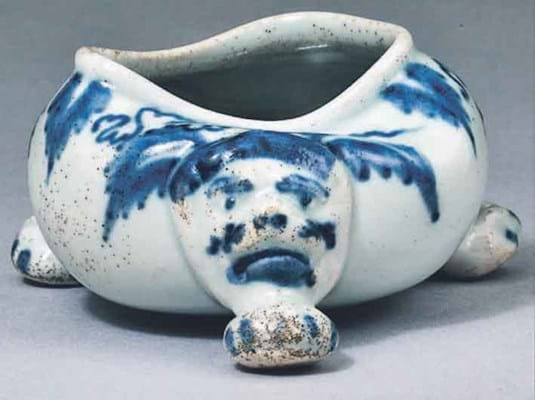

Above: this rare Limehouse salt of c.1746-48, distorted in the kiln, was one of the stars of the sale, selling for £15,000 to the auction's main buyer against bidding from another phone and the room.

All this material was more readily available when the Sutherlands first started buying in the late 1960s. Then, shells and pickle leaves from Vauxhall and Limehouse (while not identified as such) could be had for around £5 apiece.

Today, of course, following the Museum of London excavations of 1990 and Bernard Watney's scholarship, the exact nature of the output from those two early factories has been confirmed and they have risen to assume Holy Grail status with collectors.

From the standpoint of Bonhams and their vendors, the Sutherlands' sons, this was fortunate as it gave the sale a core of potentially valuable pieces. But alongside the collection's gems were a whole run of less rarified fare, like Derby and Worcester tablewares that are still widely available and whose damaged condition made them even less commercial.

Estimation was therefore key to a successful dispersal. Bonhams could be pretty bullish with guidelines on the best Limehouse or some very good examples of Lowestoft, but they had to set modest reserves on the less exciting and damaged fare.

The strategy evidently worked, given that only 33 lots failed to get away, but perhaps more noteworthy was the price polarisation.

Those things promoted as rarities attracted all the attention and saw pitched battles that took prices to multiples of the original estimates, while many of the more standard pieces got away within estimate.

On the other hand, given the large volume still available from a factory like Worcester, it probably says something that they were able to get so much damaged material away at all.

What was noticeable was the premium attached to anything perfect in the sale, like the 1765 Worcester teabowl and saucer in the Tambourine pattern estimated at £700-1000 that sold for £5800.

It has to be said that the presence of one particular telephone bidder played a major part here in the final big status results. Whoever was on the other end of Nette Megens' telephone bidding as paddle 7013 (and the name being bandied around in the trade was that of the collector Rosalie Sharp), they certainly had deep pockets, for they only bid on the potential stars and were virtually always successful.

They secured the six most expensive pieces in the sale, including the £21,000 Limehouse dish, the £15,000 experimental period Worcester teapot, the £12,000 Lund's Bristol/ Worcester early bowl and the £15,000 Limehouse salt.

That said, in every instance there was an underbidder prepared to go almost as far. The main buyer's competitors included at least one other phone and dealers Simon Spero and Billy Buck of Steppes Hill Farm Antiques.

While fashion had a positive influence on the prices for voguish factories like Limehouse, Isleworth and experimental Worcester, it had a more negative effect on those deemed less modish.

Longton Hall

The Sutherlands assembled a group of Longton Hall, a factory that was all the rage among the ceramics aficionados in the early 1960s following Dr Watney's revelatory writing on it a few years earlier. Now though, Longton doesn't carry the same cachet and there was a larger than usual number of casualties in this section.

There were also some failures among the more bullishly estimated potential best-sellers, like the near-perfect Lund's Bristol creamboat that failed to reach its £7000-9000 estimate or the rare Limehouse teapot, finely painted but minus the lid, guided at £5000-8000.

But overall this was a trademark successful dispersal in the Bonhams single-owner tradition, as the highlights and more academically interesting porcelain "incunabula" showed.