But like a work by Nicolaus Wynman issued in Augsburg almost 50 years earlier, it was in Latin and it was not until 1595 that Christopher Middleton adapted and translated Digby's text into English for "those that are ignorant in the Latin tongue" and issued it as A short introduction for to learne to swimme.

In his book, Wynman had suggested that a sound breaststroke technique might be had by watching frogs and also advised that when attempting a backstroke, one's arms should be whirled like a ploughshare being sharpened on a grindstone.

Digby's instructions, too, may seem quaint to a modern reader, but he does provide clear if sometime rather too succinct summaries of the means by which the various strokes can be mastered.

He is essentially practical and though he passes on some then current superstitions - that those born at night have stronger arms, for instance - he makes the point that swimming is a skill that can save life. He also has a modern attitude to health and safety issues, warning against swimming at night or plunging into weed-strewn waters.

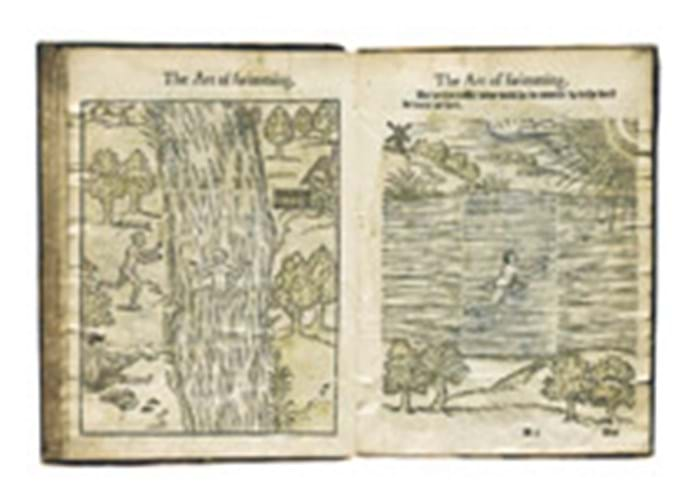

The book is illustrated with a series of over 40 crude but charming woodcuts, but there are in all only six basic designs, featuring a river flanked by trees, sometimes with cows grazing or a man sitting on the bank whilst undressing, or naked and ready to dive in.

Into these stock images are inserted rectangular second cuts that illustrate the breast stroke, crawl, etc, or demonstrate fancier skills or tricks - like treading water, keeping things dry in one's hands, even how "to pare ones toes in the water".

A copy of Learne to swimme seen at Sotheby's on October 30 as part of the vast library of the Earls of Macclesfield was made even more appealing - if that is the appropriate word to use when one is actually referring to disfigurement - by the annotations of an early owner.

Like many instructional works of the period, this one takes the form of a dialogue between teacher and student, but this reader has put his own words into the mouths of the figures: "Well leaped efaith", and "Is not ye water cold?", or "I can not get on my hoses" and "I pricke my foot".

No copy seems ever to have come to auction before and the only two other recorded examples, at the Bodleian and in the Beinicke Library at Yale, are both imperfect. In a broken 17th century binding, this complete copy sold at £74,000 to Quaritch.

By Ian McKay