Although still made today, wine labels had their heyday in 1770-1860.

These labels, also used for sauces, were typically made of silver or silver plate with materials such as enamel, pottery, porcelain, ivory, bone or mother-of pearl also in common use.

What they are not are the paper labels designed to be stuck on to bottles - that represents a quite separate field of collecting.

What Do People Collect?

There are many approaches to the study of wine labels. Some collectors concentrate on the great variety of designs, others on the multiplicity of names on labels, on the silversmiths and other makers, or on the place of manufacture.

Typically labels are grouped according to form, be they shells, crescents, ovals, scrolls, rectangles etc. One of the attractions of labels is that they accurately reflect changing taste seen in larger items of silver, from the whimsy of the rococo and the elegance of neoclassicism to the muscular forms of the Regency.

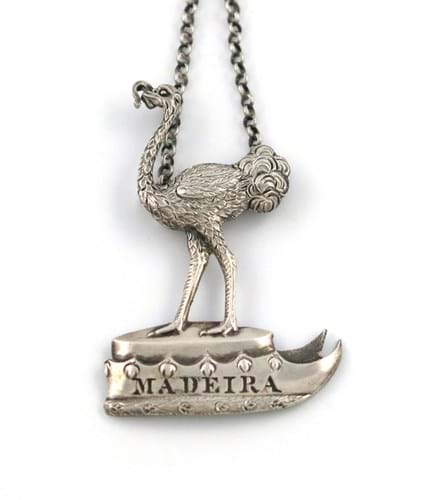

An early Victorian silver Madeira wine label from c. 1840 (unmarked) in the form of an ostrich on a cap of maintenance. The crest is that of Viscount Coke, Earl of Leicester. It sold for £600 at Woolley & Wallis in October 2019.

Labels in the form of a single vine leaf were enormously popular from the 1820s into the Victorian period, but by the 1860s improvements in the production of wine enabled it to be served direct from the bottle while legislation permitted the sale of single bottles of wine with paper labels. Accordingly, most wine labels from the second half of the 19th century are for sauces or fortified wines and spirits which could stay in decanters on the sideboard.

Names can be as collectable as forms. They shed light on the taste of their times. For example, gin occasionally appears as 'mother's ruin' or whisky as 'cream of the valley' - while long-lost vintages such as the dessert Spanish white Paxarette, or misspellings and variations, offer endless collecting possibilities.

Over 2300 names of wines, spirits and liqueurs and over 500 names of sauces have been recorded on 'wine' labels. Others carry the names of toilet waters and medicinal preparations.

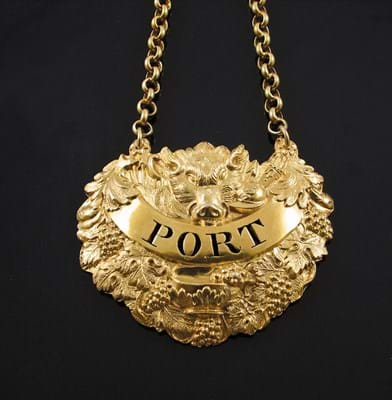

More than 500 silversmiths are recorded as having made labels during the century and a half during which they were fashionable. Alongside the luxurious cast silver gilt versions from the great London makers such as Paul Storr or Benjamin Smith, wine labels were produced by the jobbing silversmiths of regional England, Ireland and Scotland and in India and the Far East (a series of Anglo-Chinese labels in the form of fruit bats are particularly desirable).

The Market

As the winds of change in the silver market blow from the functional to the collectable, the demand for small silver and for wine-related antiques in particular has grown.

Wine labels have proved of great interest, not just to the enthusiasts of The Wine Label Circle, but to those with a casual interest in aspects of silver, wines and social history.

However, the entry level for collecting remains relatively modest. The most commonly encountered examples are from the first half of the 19th century and many are die-stamped rather than cast, a technique that allowed large quantities of silver labels to the made at a low cost.

Prices start at around £50 for relatively plain examples carrying the name of a relatively common tipple.

However, prices can rise rapidly for scarcer forms, an unusual name, a good maker, a provincial assay, or any combination of these.

Novelties such as the famous die-stamped elephant label by Edward Farrell are always desirable, while another highly collectable subset comprises heraldic labels, made for a specific family with their crest. An exceptional group of armorial labels was offered as part of the Harvey's Wine Museum sale at Bonhams in 2003.

Some collectors focus on particular makers (the neoclassical labels from the workshop of Hester Bateman are always a favourite), while collectors of provincial silver provide the crossover interest that guarantees a premium.

Plated labels or those in other materials are typically cheaper than the silver versions but the transfer-printed and painted labels produced in enamel at Battersea are both rare and desirable.

Further Reading

Wine Labels 1730-2003. A Worldwide History, ed. John Salter. ISBN-10: 1851494596

Sauce Labels 1750-1950 by John Salter. ISBN-10: 1851494316