That, at least, was the theory. In fact, relatively little Irish ‘provincial’ silver made the journey to the metropolis to receive official approval – for reasons of security and economy.

It is a 320-mile round trip from Cork to Dublin, and, for those carrying precious metals by coach or on horseback in the 18th century, a dangerous one. It could be expensive in other ways too as every ounce of silver assayed by the crown incurred a duty of six pence.

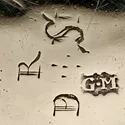

Instead, as early as 1710 silversmiths in the prosperous ports of Cork and Limerick were exercising their own quality control and stamping their wares with the words Sterling (or occasionally Dollar for those wares made from Spanish coinage) rather than the crowned harp of Dublin. Those in Galway, Kilkenny, Kinsale, Youghal and Waterford stamped their wares with maker’s initials only.

Ultimately it was the Act of Union in 1800 that made it cheaper to import silver from Sheffield and Birmingham, rather than regulation, that led to the decline of Irish provincial silver by the 1820s.

A Collecting Hierarchy

The appeal of Irish provincial silver lies primarily in the rarity. The melting pot has claimed large quantities over the years.

Silver made in Cork, a city with the cultural, financial and social means to support a number of silversmiths, is far scarcer than that made in Dublin, while surviving pieces from Limerick and beyond can today be counted in the tens rather than the hundreds or thousands.

But an equal part of the allure of Irish provincial silver is its idiosyncratic vernacular style.

Collectors left cold by the sometimes anodyne productions made in Georgian Dublin can have their heads turned by the contours of a Cork sauce boat or the beguiling simplicity of a sugar bowl from Kinsale.

Regional Irish silversmiths fully understood the dominant European design style of the day, but – sometimes a few years behind the curve – they chose to interpret them in their own way. Provincial wares are seldom slavish copies of metropolitan taste.

The Market

Buyers Irish provincial silver come from across the global Irish diaspora. The current market relies heavily upon the input of international collectors and many important pieces sold in Ireland go abroad.

It is worth mentioning that the huge premium now placed upon items with provincial Irish marks has been the stimulus for fakery. Typically unmarked objects will reappear on the market with strikes for silversmiths from Limerick, Galway or beyond, although a more complex issue is the ‘de-chasing’ of 18th century silver – the removal of later rococo-style decoration applied to meet the fashion of the Victorian period.

Erasing later engraving can be straightforward restoration but in the hands of a creative silversmith, it is possible to go further. Ultimately, it is about intent and transparency.

Further Reading

Cork Silver and Gold: Four Centuries of Craftsmanship by Conor O’Brien and John Bowen, 2005

A Celebration of Limerick’s Silver by Conor O’Brien and John Bowen, 2007

500 Years of Irish Silver by Ida Delamer and Conor O’Brien, 2005

Irish Georgian Silver by Douglas Bennett, 1984