As part of one of the world’s fastest-growing economies, the rising numbers of Vietnamese-born ultra-high net worth individuals are an increasing force in the international art market.

Comparisons with China are premature, but it has been enough to push the best works of art from the Le (1428-1789) and Nguyen (1802-1945) dynasties to uncharted territory in recent years.

In October, an elaborate headdress worn by a first-rank Nguyen court official took €600,000 (£509,000) at Barcelona auction house Balclis, while a new record was set for Vietnamese ceramics in June 2020 when a large 15th century blue and white storage jar sold for a surprise €380,000 (£340,000) at Christie’s Paris.

It was during the Ming occupation that blue-and-white decorating technology was first introduced to Vietnam, spurring the development of a local ceramics industry. However, from the 1700s onwards, it was more typical for the local ruling class to order their porcelain from China.

The so-called bleu de Hue wares (named after Hue, the Nguyen capital and site of the Forbidden Purple City) were made in Jingdezhen to Vietnamese designs, often including the bespoke marks of royal family members and court officials.

Enter the dragon

Extraordinary sums were achieved for Nguyen bleu de Hue porcelain at Adam’s (25% buyer’s premium inc VAT) in Dublin on November 23.

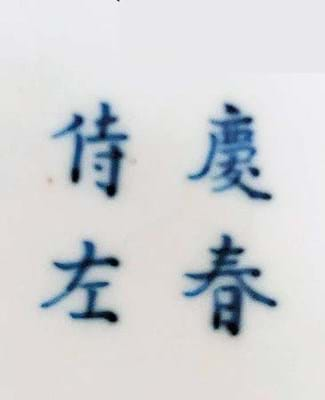

The most valuable of these was a 6½in (16cm) plate finely decorated with a dragon, a qilin and the khanh (happiness) and tho (longevity) symbols. The four-character mark to the reverse reads khánh xuân thị tả (Eternal Spring, Left Palace), a reference to a residence owned by the Trinh clan, the family that dominated the royal court in the Later Le period. It had a protective silver rim of the type that became popular on Vietnamese porcelain in the late 19th century.

A similar plate in the collection of the Museum of Royal Antiques of Hue formed part of the influential 2018 exhibition Signed porcelains from the Lê, Trinh and Nguyen Dynasties. Many of these pieces came to Europe in the years under colonial rule. From the aftermath of the Sino-French War in 1884-85 until the last months of the Second World War, the Nguyen emperors ruled only nominally as heads of state of the French protectorates.

Two pieces with a similar decor and an identical mark have appeared at auction at the Drouot in Paris in the past decade: a plate sold by Asian specialist Asium in June 2019 for €78,000 (£71,000) and a bowl sold by the same firm in October 2019 for €85,000 (£77,000).

Adam’s plate also came from France, consigned via specialist Thibault Duval with a guide of €6000-8000. In perfect condition apart from a very light hairline in the glaze, it flew to €140,000 (£127,300).

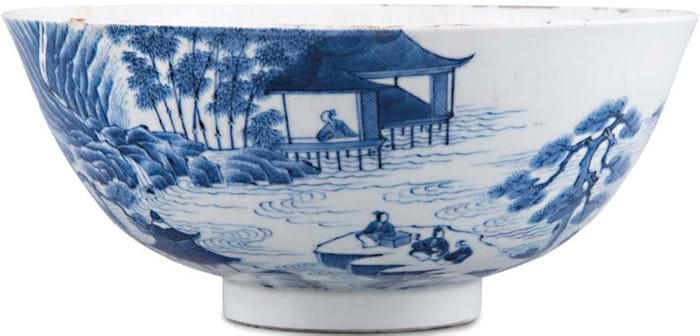

A yet greater improvement on expectations was provided by an 8in (20cm) bowl decorated with a continuous river landscape, daoist immortals and go players.

A cobalt blue mark inscribed to the base reads jǐ sì nián zhì –the jǐ sì dating this bowl to a year of the snake (maybe corresponding to 1869). It had a few condition issues (probably missing a metal rim, there were small chips and abrasions to the rim) but made many times its estimate of €600-800 when it sold at €40,000 (£36,400). Both pieces sold to Vietnamese collectors.