Geoffrey Munn holding the 19th century silver gilt Nepalese prayer ball.

Image copyright: Charlie Carter

An expert on the BBC’s Antiques Roadshow, his new memoir, A Touch of Gold: The Reminiscences of Geoffrey Munn, includes a chapter on collectors and collecting. He himself collects notable objects for his Kunstkabinett, a cabinet of curiosities.

ATG: How did you get the collecting bug?

Geoffrey Munn: When I was about 11 we used to live in Henfield, West Sussex, and take the bus to Brighton for 1s 6d. The Lanes had really quite sophisticated antiques shops at that time with ethnographical things and all manner of good objects.

And then endless visits to country houses like Parham Park and museums.

I had a collection of animal skulls, as boys do. My mother found them much less interesting than I did. I went to boarding school; when I came back they weren’t there.

What is a Kunstkabinett?

It’s a concept very fashionable in the 16th and 17th centuries when it was firmly believed that God had created the world in six days and the seventh day took a day off. So they had absolutely no idea what the wonders of the natural world were, except that they were created by God and that was a certainty, and so they accumulated and marvelled at them.

In their Kunstkabinett, natural objects - the unicorn horns, shells and far-fetched things from abroad nuzzled works of art. A unicorn horn was thought to deflect poison and bad influences. Of course it was narwhal tusk.

What drew you to creating your own cabinet of curiosities?

The great thing about the Kunstkabinett is that anybody can do this because it includes things of absolutely no value whatsoever jostling with things that might be really quite costly. All you need is the shelving.

I’ve seen them in antiques fairs since I was 19. There was a natural recess in the wall and so it needed filling. It’s probably been there about 13 years. I keep adding to it.

What are some favourite objects in your collection?

I’m rather into charms and talismans because I find it absolutely riveting that people believed in magic so wholeheartedly, and it ran completely concurrently with Christianity.

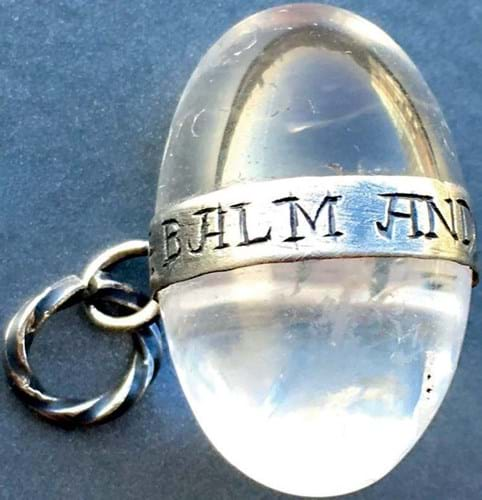

One of my favourite ones is a rock crystal ball bound in a sling of silver; it’s very much associated with curative properties. It is probably 16th century. It was believed that these stones were imbued with magic, that you drop it into water and swirl it around and then you could transfer that magic with the water.

I was very thrilled to get another one which illuminates all of this because it’s got a little sling on it that says quite simply, + Balm and Rest +. So it’s obvious that that’s a curative object from the 17th century.

Memento mori is ever present in the Kunstkammer - hour glasses, pomanders, skulls and mirrors - because there is an interest in the transience of life. A particularly graphic skull I have, complete with articulated jaw, is a 17th-century silver pomander. There is a strongest sense that scent is a permanent moment mori because if you can smell it, then you’re alive. It would also cover presumably unpleasant smells that were absolutely everywhere in the past. You wear those on your belt.

Another skull pomander I have from the same period is to carry in your pocket. This one opens and there would be little pills in spaces labelled nutmeg, rosemary, thyme and something called schlag. It’s almost like homoeopathy in a way that if you had the tiniest amount of these quasi-magical essences, it was enough. Every single plant had a very particular curative power.

How about things from the natural world?

I have a 17th-century talisman called a bezoar stone and it’s certainly organic. It’s some sort of weird concretion from the innards of ruminants. If you like, it’s almost like a gallstone. For some reason or another the bezoar was thought to be a very powerful agent against poisoning. To protect yourself, you brought it near your food and if you were thinking you really were up against it, you’d scrape it and put some of it in your food.

But the fact that it is mounted in silver is a hint that it’s valuable. There are ones mounted in enamelled gold in German collections. The bezoar stone itself was more valuable than gold in the Renaissance and they were much sought after.

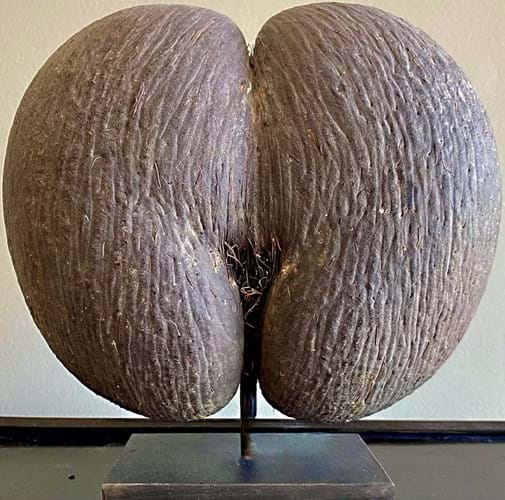

I have a rather naughty-looking coco de mer, which is visually ambiguous, and shells are terribly important to cabinets of curiosity.

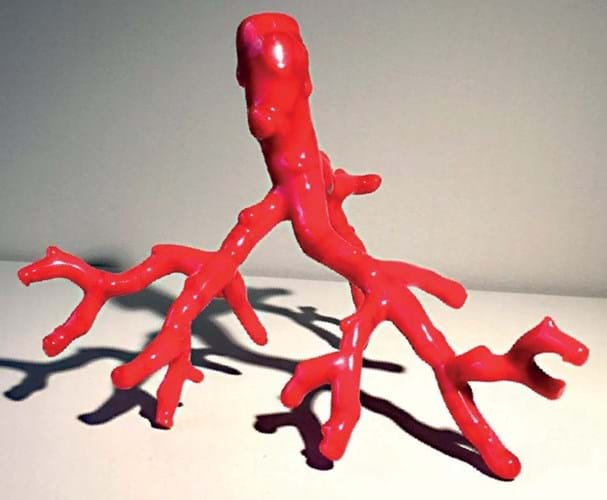

There is a very vivid branch of coral but it’s actually not coral at all, it’s glass, so there’s illusion in there too.

What elements do you look for when considering a purchase?

Not necessarily beauty - because the bezoar stone is certainly not beautiful - but context. They’ve got to fit into a scheme of the cabinet of curiosities. You look for resonances between one object and another.

Would you classify your habit as buying the best there is, or are you driven by the thrill of having something that somebody else has missed?

My late boss, Kenneth Snowman, chairman of Wartski, said you never regret your extravagance, only your bargains. There’s something in that at a higher level that the more costly the object is, the more likely it is to be beguiling and attractive, and to have the same effect on the next generation so it will continue to be valuable.

But value is a completely false barometer. The late British art historian John Pope-Hennessy said there’s absolutely no relationship between a work of art and its value, and that is completely true because passion plays such an important role in all of this.

There are all kinds of reasons to buy and to collect, and it should be some weird, indefinable love affair because ‘lurve’ is not very definable either. It can happen quite arbitrarily and we can’t articulate it. The same goes for objects.

Where do you find items to buy?

All over the place. People do say, “Well, how do you find all these things?” And I’m pretty severe with them. I say, “By getting out on the town”. You have to go to the antiques fairs and look at various sales, and sometimes it can be very exciting indeed.

What’s the most you’ve spent on an item for your Kunstkabinett?

Thousands. The least is £2 for a palm nut, which is one of my favourite objects. It rattles rather beguilingly with the seeds in it and it feels like Japanese lacquer.

How large is your collection?

It might be 100 pieces by now.

Have you sold items from your Kunstkabinett?

No, not one. You’d say that’s quite weird, working in Wartski all those years and being a dealer, but this is a private thing. If I’ve sold anything personally I’ve always regretted it.

Is there one object you’re still looking for?

I want a unicorn’s horn but I don’t want a whole one because of its size. And now, of course, there is quite a problem with any kind of ivory. Narwhal ivory has now become embargoed so I doubt I’ll ever have a unicorn’s horn, but that would be very nice mounted in enamelled gold. There’s one in the V&A called the Danny Jewel. It is a fragment of narwhal tusk, believed to be unicorn, and it would have had massive curative properties.

What advice would you give a young collector?

Start with shells, fossils and plant life. Exotic nuts and dried flowers can look hugely interesting in there and cost nothing really.

For a very young collector with a very limited budget, that’s a good place to start, with the firm assurance that their collecting is going to go on and on and on, and cost more and more and more.