Eschewing mass production meant output was limited, so it was interesting that two recent design auctions featuring his work should be held within the space of just a week, bringing no fewer than 30 pieces to market.

The first took place in Copenhagen at Bruun Rasmussen (24% buyer's premium) where five of his pieces featured in the auctioneers' 262-lot sale of Nordic Design held on March 6.

Then in Paris at Piasa Rive Gauche (23/20/12% buyer's premium) on March 12, the auctioneers offered a catalogue of 25 lots of furniture that Moos had created for the Manoir D'Ostrupgaard in Jutland, Denmark, from 1942-45. This separate catalogue was offered immediately prior to a larger mixed-owner sale of around 250 lots of Scandinavian, American and Brazilian design.

The son of a farmer who studied under Kaare Klint at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Moos formed his own carpentry furniture studio in Jutland then worked in Paris and Switzerland in the inter-war years before setting up his own workshop in Bredgade in Copenhagen in 1935. In the 1960s he moved to Bredebro in southern Jutland.

Moos' hand-crafted approach and use of materials (almost always wood), plus the adoption of dowels and wedges instead of screws and his preference for a finely sanded finish, links him more to the Arts and Crafts movement than the mass production of modern design. In fact, his work straddles both camps. With its clean spare lines and reliance on wood grain and restrained touches of inlay, it also has much in common with Scandinavian inter- and post-War Modernism and Moos had a lasting influence on Scandinavian post-War design.

"There simply isn't enough Peder Moos to start a collecting culture," observed Bruun Rasmussen's design specialist Peter Kjelgaard, who feels instead that his work is more generally appreciated by those who collect Scandinavian design.

Within the admittedly narrow confines of his oeuvre, the two consignments of Moos furniture offered last month were at opposite ends of the spectrum.

Embassy Commissions

Bruun Rasmussen's pieces were more complex creations in combinations of exotic and native woods like rosewood, walnut, maple, elm and box with small subtle inlays. They included a delicate, almost airy glass-topped tea table in rosewood with box inlay made as a special commission for the Danish Embassy in Washington in 1956 and a 1960's walnut sewing table opening to reveal a compartmented drawer.

The 25 lots of furnishings that Moos had created for the Manoir d'Ostrupgaard in Jutland were a wartime commission and simpler in conception. Virtually all were made from pine, the only wood available at the time, and were unadorned except for the decorative 'marquetry' effect from the use of dowels and wedges.

The five Copenhagen lots, which came from three different sources and were first under the hammer, all found buyers, four of them at prices that were above estimate.

Topping the bill at a double-estimate DKr540,000 (£63,230) and up there with some of the highest prices paid for Moos' work was the Danish Embassy tea table. A piece which was beautifully worked right down to the pierced circular wooden castors and signed with his distinctive marquetry monogram, it had featured in the Copenhagen Cabinetmakers Guild Exhibition of 1946.

"It was so detailed it really stood out in comparison to the other pieces," said Peter Kjelgaard.

Following at DKr150,000 (£17,565) was a 21in (55cm) high four-shelf wall cabinet in solid walnut with maple joints and a pair of tambour-fronted doors, signed with a monogram. From the same vendor came the 2ft 1in (66cm) wide, slender-legged sewing table made from the same materials. This came with the original receipt and care instructions and made DKr145,000 (£16,980).

The other two lots - a solid walnut monogrammed pipe stand with eight holders also from the same vendor and a signed nest of three small tables in solid elm with circular boxwood inlays - realised DKr14,000 (£1640) and DKr110,000 (£12,880) respectively.

Attractive Provenance

The 25 lots that were offered for sale by Piasa were more of an ensemble, having been created to furnish a specific residence. They ranged from three dining tables and smaller occasional tables to three-legged stools, a serving trolley, a desk, two day beds and various smaller fittings like mirrors and coat hooks. These had remained within the same family and this provenance presumably gave them an added attraction.

Here there was more variation in the results. Nine lots failed to sell but, of the 16 that found buyers, around half a dozen went way over estimate while the others sold more in line with expectations. Frédéric Chambre, Piasa's vice president, felt that this variation was determined by personal preference: what people deemed significant or aesthetically stylish pieces and what was easiest to display.

Buyers, he said, were an international mix of American, Scandinavian and other Europeans.

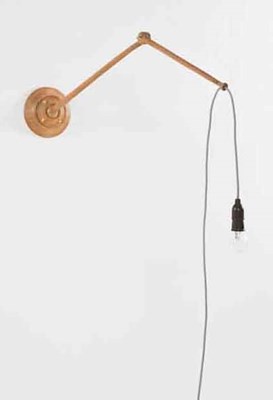

Perhaps the most dramatic result here came with one of the smaller fittings and one of the few non-pine creations. This was an adjustable wall light of 1943 made from beech with brass screws and looking for all the world like a side-mounted Anglepoise. Piasa's estimate of €8000-12,000 was left behind as the bidding sailed to €44,000 (£38,260).

The same price was paid for a pair of 18½in (47cm) wide occasional tables, one signed 1944 Moos on the underside, the other dated 1944. They had been guided at €12,000-15,000.

The opening lot, a 5ft 5in (1.65m) pine trestle-ended dining table of the same date, realised €40,000 (£34,780).

By contrast, the highest estimated piece, a bureau with three pullout leaves and a compartmented pedestal from 1942 which was signed on the pedestal shutter, came in towards the lower end of its €30,000-50,000 guide at €36,000 (£31,305).